In my continuing pursuit of humility as an antidote to modernity’s human supremacy illness, the atoms that constitute who I am take issue with lofty and self-aggrandizing concepts of idealism, dualism, and free will—replaced by the unflattering material world and its staggering wealth of emergent complexity. I have argued that opposite of lacking imagination and being reductionist, such a view far exceeds our imaginative capacity and is in fact rather expansive and open-ended next to facile short-cut cop-outs that sweep mind-boggling complexity under the rug by pretending that constructs like mind, consciousness, soul, God, or Santa Claus are real.

One stubborn sticking point is the beguiling illusion that “we” are separate from “our” corporeal bodies, owning and controlling them, somehow. This notion is prevalent, despite zero evidence that we are anything but corporeal, and heaps of evidence to the contrary. A less supremacist variant allows that all life, down to microbes, are endowed with this material override to exert control and autonomy over their environments, but still demand a line of separation between life and inanimate collections of matter. An amoeba suddenly changing course in reaction to its environment is, in this view, ontologically different than a hurricane changing course in reaction to its environment.

Granted, life is amazing and exhibits unambiguous behavioral differences compared to, say, rocks (hint: check the complexity of internal structure). A materialist, mechanistic basis does not in any way diminish life, although that’s often the regrettable reaction from someone who takes it on faith that transcendent mystery accounts for life’s splendor—rather than intuition-busting eons of emergent material fabulousness. Well, it turns out that life is incredible no matter what inconsequential thoughts we form about it. In any case, the point that I will develop in this post is that “decisions” are carried out at every level from electrons to ants, but are at no point fundamentally operating on a different basis.

Depending on how one defines “decisions,” either electrons and bats carry them out by the same rules, or neither can be said to be making “free” decisions. Whatever the case, electrons and bats are on similar footing when it comes to “decisions,” albeit at vastly different scales of complexity. Given enough information and background, the decisions by either are not surprising, even if not precisely predictable. Now, I do identify a difference between living decisions and inanimate decisions, importantly, but it’s a subtle one that I’ll wind my way toward.

Stimulus–Response

So, how do decisions differ (or not, fundamentally) between life forms and inanimate objects? Lots of non-living entities appear to make choices. How many times have you heard a non-living entity described as “having a mind of its own” in reaction to execution of inscrutable behaviors? Whether discussing individual electrons, amoebas, or newts, we might characterize the decision process as being centered on stimulus–response, to varying degrees of complexity.

As my suspicions are aroused by any claim of an ontological gap counterfactually separating life from a material world, I am drawn to explore the putative difference between “decisions” made by electrons, rocks, spores, seeds, storms, microbes, plants, ants, and humans. My premise is that they are arranged on a continuum of complexity, but nowhere break away to operate outside of the laws of physics, staged on a material plane, following the unscripted script the universe writes in real time.

Inanimate Decisions

Newton’s Cradle, by GeoTrinity.

In pondering inanimate decisions, some physical systems really do seem to be making informed decisions. You’ve probably seen or played with a Newton’s Cradle, even if not knowing it by that name. Gracing many an office desk, these steel balls arranged in contact along a horizontal line are each suspended by a pair of strings or wires in a V-configuration. Pull one ball back and release, to find that when it hits the queue with a clack a single ball emerges from the other side. Start with two balls and two pop out the far end. Even if the chain is only five balls long, drop three and three come out—the middle ball somehow knowing it has permission to continue on. How does the device know the number of balls you released? Yet it does every time. It’s a simple matter of simultaneous adherence to conservation of energy AND conservation of momentum. The balls have no other choice. I’m convinced, though, that a large part of its lasting popularity is the appearance of “magical” decision-making. Here, “magical” means without a brain, which we dumbly and self-centeredly assume is necessary for making decisions.

This relates, by the way, to my experience teaching physics classes and often bringing in classroom demonstrations. Students are consistently most engaged when the demonstration exhibits unexpected behavior. The closer it is to “magic,” the more fascinated students become. After all, we’re well habituated to “ordinary” physics all around us, to the point that it becomes mundane.

As another example, if you’ve ever held a corner cube prism, or retroreflector, it has this eerie habit of always showing your eyeball in the center, no matter the orientation (within limits). Because I shot lasers to these devices positioned on the moon, I generally had one at-hand in my office. What always seemed like magic to students was asking them to close one eye, then switch which eye is open. The corner cube prism “knows” immediately which eye you are using. It’s a simple passive bit of optical geometry, but it really feels like it’s tracking your actions.

Anyone who bikes on urban streets has no doubt run across collections of detritus (broken bits of tail light covers along with other trash and collision remnants) in places where car tires don’t tend to go—like the exact center of an intersection. But bikes, exercising their habit of avoiding cars, often end up going where cars do not, encountering these pockets of debris. How do all these bits know where to congregate? It’s the same as dust bunnies or pet toys all finding refuge under furniture. For that matter, it’s the same as water vapor in the room’s air finding your iced-drink glass and collecting on the outside. Wherever it’s “cold” (meaning reduced jostling), things will be jostled into such places and once there are not jostled out again. The general term is condensation. Related phenomena can account for concentrations of ores, fossil fuels, etc.

At its most basic level, one might ask how an electron decides where to go next. Well, it of course depends on the positions, velocities, and spin orientations of all the other particles (in the universe). Even though it executes a decisive path, it fundamentally has no other choice.

Now imagine, if you can (and no one really can), the same sort of mandates applied to complex systems all the way up to thoughts. Some folks seem to believe that thoughts and ideas are not material in nature, but holy cow: just try to have a thought without complete material dependence! Yes: even thoughts are made of atoms and their arrangements/interactions. We are nothing and can do nothing without them. Not a shred of evidence advocates otherwise: only affinities and untethered fabrications.

Border Cases

Before we get to living decisions, it’s worth a brief stop at seeds and spores. These can’t be called inanimate, per se, as they are stages of life (intricately structured material containing DNA and everything!) that might remain completely inert for tens of thousands of years in the case of seeds, and hundreds of millions of years for spores! Metabolism is completely stopped. No processes are transpiring inside. It’s just waiting—dormant. It may ultimately “decide” to spring into action, but that decision is not taking place in the interior: the organism is really just “off,” and operationally indistinguishable from “dead.”

When the outer surface senses appropriate conditions (moisture, nutrients), it may re-animate. But what is the nature of this decision if the structure is completely static and inert? What aspect of life is making this decision? What is the stimulus–response pair?

Imagine a mechanical (molecular) receptor shaped just so that when a correctly-shaped molecule (e.g., a nutrient) comes into contact, it fits perfectly, tripping the receptor molecule, which opens a channel through the protective shell to re-open the cell for business. The decision is purely mechanical, like a key unlocking a coiled spring waiting to be triggered. I would go further to say that every decision is fundamentally mechanical, but this one is a simplified version, removing the many layers of complications found in a fully-living, metabolizing entity. Through seeds and spores, we can see that life’s most important decisions can be carried out by mechanistic material interactions.

Life’s Difference

The key, I believe, to what makes an ant’s decisions different from a rock’s or an electron’s is: feedback: a closed-loop. An ant’s decisions bear on its ability to stay alive, facilitate reproduction, and remain an ant. An ant incapable of making life-sustaining decisions can’t be an ant. Conversely, a hurricane may decide to veer, but this decision is not part of a closed-loop that determines whether the hurricane can pass on its genetic code and propagate hurricanes into the future. The very setup of life, in an evolutionary, ecological context forces the kinds of “decisions” that enable the whole process to persist.

Life exists in a context of self-replication, evolution, relationships to other beings, and as such has developed a set of mandated behaviors we call decisions that are part and parcel of this capability. More exactly, organisms develop mechanisms to express observed behaviors that necessarily support continued existence. For life to work, it must develop the ability to react to the environment, and those reactions are shaped and refined for their selective benefit. If life failed to make “correct” decisions (complex responses to complex stimuli), it would perish and no longer be life. Life has no choice but to make the choices it appears to make.

Circular Reasoning?

One might object to the apparent circular reasoning exhibited above, which merits an aside. Circular reasoning, or tautologies, acquire a bad reputation in learned discourse. I hold that this disparagement is more a flaw in the conventions of learned discourse than anything intrinsically discreditable. Another term for circular reasoning is: self-consistent. And what could be so bad about that?

The truism that “it is what it is” stands as a decent representative of unassailable circular logic. The universe contains something rather than nothing because it does…and without pausing to ask our permission.

At its core, I believe the “circular objection” to be yet another expression of human supremacy. Just as our culture discounts the problem-solving acumen of early microbial life because they cheated and didn’t solve the toughest problems in the world with brains, we eschew circular reasoning because it highlights a sort of truth that is not of cerebral origin. We can’t take credit for it. Therefore it doesn’t count!

Never mind the fact that amoebas and their genius kin have solved problems that baffle our best brains to this day, to the point that we are utterly incapable of conjuring even the simplest of its tricks using our neurons (without simply parroting our smarter microbe teachers).

The same kind of protest arises in adjacent realms, such as the common reaction to determinism: “If I can’t drive the train, then what’s the point: I refuse to ride along.” Similarly, it comes up in discussions of free will: “I can make free choices [free of what: physics?] because I am a separate entity in control.” Discussions of mind or consciousness produce a related reaction: “Mind, consciousness—essentially soul, really—exist independent of (or at least alongside) the material plane” in a scary sort of dualism. And in this case: “Circular reasoning doesn’t count as proper thinking because it removes the motivating agent (human mind) from the argument.”

Gee. That sounds like the actual universe as it exists: going about its amazing business well before the recent addition of cerebral life. I’m more than okay with that.

Inanimate Tautologies

Circling back to where we were before our digression, I proposed that life must make the sorts of decisions that are necessary to maintain life—in a tidy tautology.

In order to better explore the essential nugget, here, I was compelled to go beyond Newton’s Cradle, congregating dust bunnies, veering hurricanes, and the like to seek more self-referential decisions among the inanimate. In other words, if an entity failed to make a certain decision, it would no longer exist as that entity. Here are a few initial stabs. Perhaps in the comments, folks can expand the list (and do better than I have).

A river “decides” to flow downhill (gravity and topography play key roles), but if—for whatever reason—it was prevented from doing so, then it would no longer be a river, would it? Maybe a lake. If a sudden logjam blocks a river from its normal course, it might decide to erode a bank, topple some trees, and form a new channel. That’s just a river deciding to remain a river!

A stalactite chooses to remain bonded to the cave ceiling—a decision we can more easily trace to mechanical conditions and material properties than we are able to do for decisions involving more complex processes. If, for whatever reason, it failed to adhere to that decision, it would no longer be a stalactite.

A long, thin spit of sand seems impossibly fragile, yet its presence alters the actions of currents and waves in such a way as to maintain and even extend itself. Its continuance depends on its agency in altering the decisions of sand, water, and wind to operate in its favor.

Photo of Dungeness spit in Washington, by Nat Bocking.

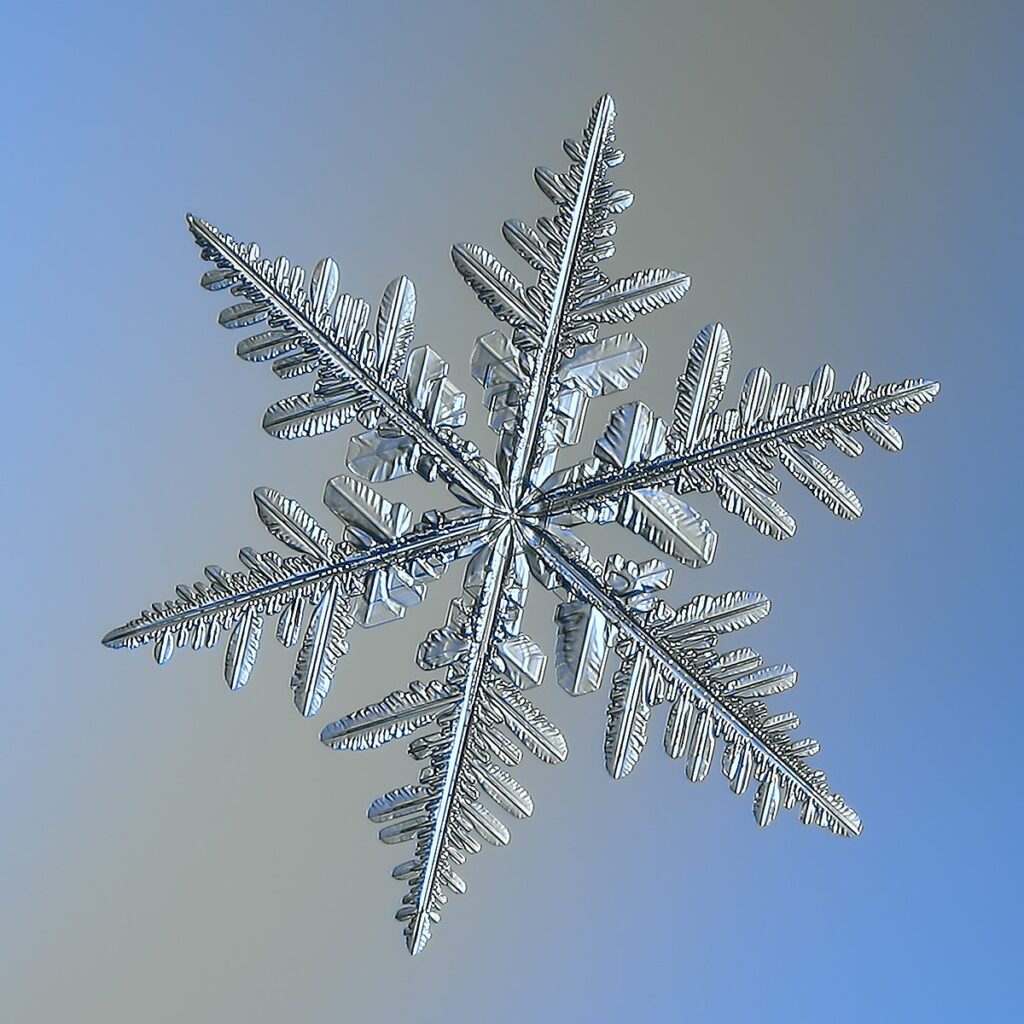

Likewise, snowflakes grow into snowflakes because they have the structures of snowflakes. That is, the presence of ice forms structured nucleation sites for other vapor to join the ice in orientations that self-referentially reinforce initial orientations to make elegant designs. Water molecules decide to attach in ways that preserve and innovate these unique structures. Yes, physics absolutely guides the decisions, as in all cases.

Exquisite self-made structure of a snowflake: loads of decisions in there. Photo by Alexey Kljatov.

At the grandest scale, our universe is quite plausibly one of a multitude, each “choosing” different parameters governing its physics (a la Landscape ideas). Only those landing on conditions conducive to making stars, planets, chemical diversity, and billions of years of stability are likely to be inhabited by the likes of us. It’s a (natural) selection effect wherein the initial choice determines whether some internal component may one day call the thing a Universe—not that such a moment amounts to a hill of beans as far as the universe is concerned.

Although not an inanimate case, an example from one of my favorite movies, Galaxy Quest, helps illustrate. The Commander was asked about a decision to save his crew instead of prioritizing his own survival. His answer: the Commander can’t be a Commander without a crew, so the decision is built-in as a self-referential, self-fulfilling, tautological certainty.

Back to Life

It’s possible that these examples seem trivial, circular, pointless, or lacking a “there” there. But I contend that an essential truth is contained in the self-consistency of each.

If life had not availed itself of mechanisms to assist in the securing of essential nutrients and resources to facilitate its self-replication, then it wouldn’t be life. The mechanisms may be too complex for us to grasp using puny meat-brains—being based on neurological mechanisms selected for different purposes. But the seed or spore provide a window into a stripped-down form of decision-making that more evidently comes down to a mechanical process—rather than some ethereal higher-plane assessment—since the interior is completely inactive and non-participatory.

Life makes decisions because decisions make life. Rivers flow because failing to do so would terminate their status as rivers. Every action in the universe, down to the motion of en electron can be cast as a decision, always based on simultaneous assessment of many factors/stimuli, and always obeying the laws of physics. Nothing has any freedom to do otherwise. Just because our brains are incapable of tracking the complexity of the mechanisms that lead to decisions at the level of life does not invalidate the basis. How grandiose to imagine that we have a say in the matter!

For me, this perspective only serves to enhance appreciation for life. It serves humility. It places me deep within the tangle of the material universe in all its diversity. It connects me intimately to every living and non-living entity—which is the way of things whether I’m ready to acknowledge it or not.