Providing care to people in need is usually seen as supremely humane and ethical. But look more closely and you’ll find that “care” is often a vehicle for self-serving social and political control. It’s often considered acceptable to withhold care from people who don’t have the “right” citizenship, skin color, cultural background, or gender identity, or who don’t have money to buy the care they need.

For an illuminating deep dive on the politics of care, check out a new book, Pirate Care: Acts Against the Criminalization of Solidarity (Pluto Press). I interviewed two of the co-authors — Italian activist Valeria Graziano, now living in London, and Croatian activist Tomislav Medak — in my latest Frontiers of Commoning podcast (Episode #58). The third co-author is Croatian activist Marcell Mars, now living in Coventry, England.

Pirate Care is an omnibus term coined by the authors to describe acts of care that defiantly challenge the “organized abandonment” of people in need. In the tradition of civil disobedience, pirate care activists intervene in situations to show organized compassion and social solidarity for ordinary people.

In the process, they also aim to show how the state, markets and patriarchal families are the ones decided who is deserving of care, and on what terms. Certain types of care are seen as unpatriotic, a threat to business revenues, or unacceptably kind to marginalized people.

Pirate care spans a wide gamut of activities: feminist actions to strengthen the right to reproductive healthcare; peer support for mental health and trans health and well-being; free access to knowledge whose publication has been banned by the state or copyright laws; struggles for affordable housing and collective childcare; and organized support for migrants and against racism.

Graziano, Medak and Mars are all frontline activists with a wide range of experiences. Valeria Graziano has worked on such issues as precarity, coercive unpaid labor, workfare, and gendered oppression, in Torino, Italy, and in England.

Tomislav Medak has spent more than twenty years contesting the privatization of property and copyright expansion while trying to collectivize the production of knowledge through commoning. With Marcell Mars, Medak created a peer-to-peer pirate library called Memory of the World https://library.memoryoftheworld.org that is curated by amateur librarians around the world who federated their collections of books.

The three coauthors point to many factors that have corrupted the institutionalized care, including “normalizing nationalistic logics and administrative harm,” the “weaponization of professionalism as an alibi for neglect,” and the “selective providing of welfare benefits to reinforce social exclusions.”

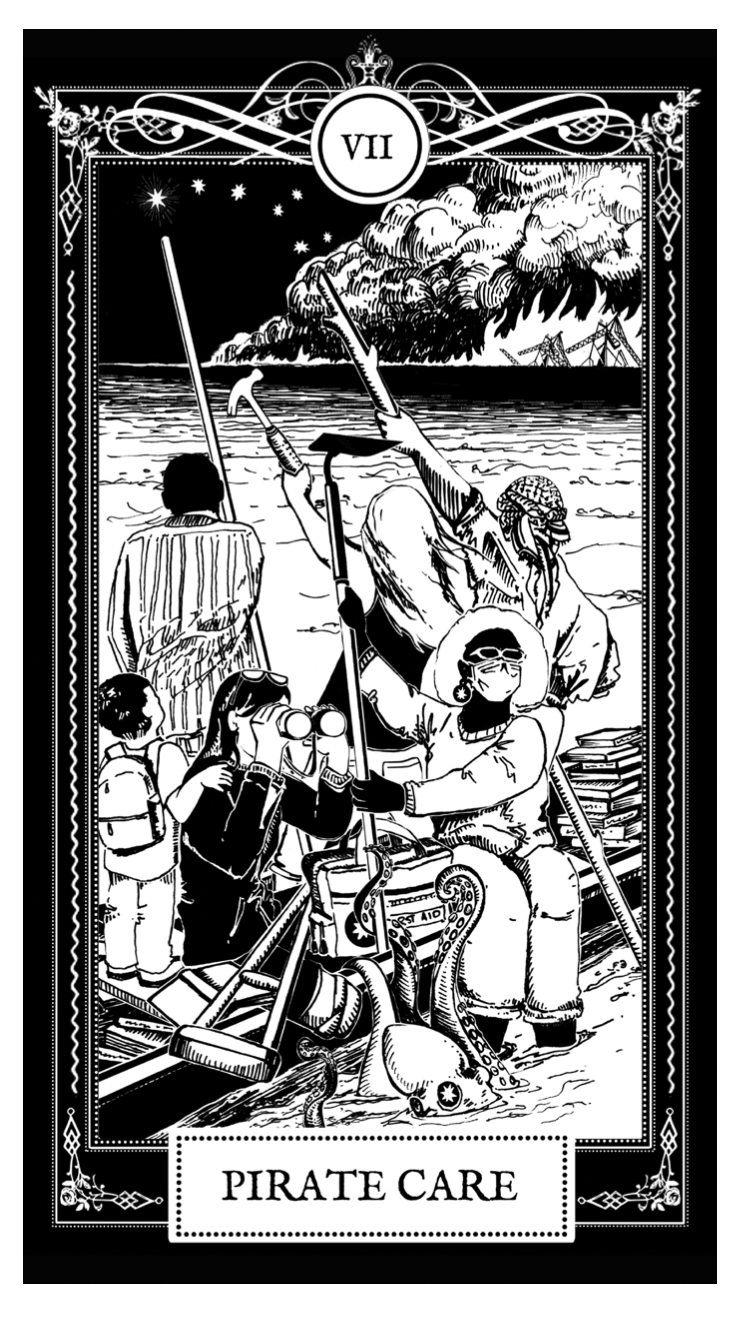

Frontispiece to the book ‘Pirate Care’

They also cite the façade of government support for healthcare, social housing, education, and unemployment as a problem. In practice, state care institutions have been hollowed out through “chronic underfunding and managerial subversion of benefits” — a process they call the “zombification” of care institutions.

So there are all sorts of subtle and not-so-subtle ways in which care is hijacked and turned into an instrument of political bullying and coercion. Hence the need for pirate care: a strategy to call out such subterfuges and inaugurate new types of socio-political debates.

Every year, the European Union lets more than 2,000 people die while crossing the Mediterranean. So, to rescue migrants who might otherwise die on the high seas, a project called Sea-Watch helms its own ships to prevent drownings and bring people safely to shore.

Another project, Women on Waves, is a mobile clinic on a ship that works in international waters, outside of the territorial boundaries of nations, to bring reproductive healthcare services, including abortion pills, to women who otherwise find them difficult or illegal to get.

In another act of pirate care, a Freedom Flotilla used two small ships to bring food, electricity, and medical supplies to Palestinians in Gaza in 2008, evading the Israeli governments blockage of the Gaza port. The daring and dangerous act of bringing humanitarian aid to Gaza brought international attention to Israel’s human rights policies toward Gaza — and inspired later flotillas of aid after the current genocide began.

It should be no surprise that pirate care seeks to have theatrical and political bite. Its creative public interventions try to trumpet how care has been politicized by states, markets, and religious reactionaries. Care has been cast as a privilege reserved for people approved in advance by “the Empire,” as they call it.

The book Pirate Care is an attempt to give a name and concept to the varied forms of insurgent care in the world. It’s not just a matter of “courageous activists on the high seas, but also organizers taking back housing in gentrifying cities, hacker librarians liberating ‘intellectual property,’ trans collectives cooking up homemade hormones, and many more pirates, including many whose actions operate under the radar of the imperial armada…”

Pirate care may involve providing meals to homeless people in Texas; supporting farmers who share seeds to grow food (in defiance of laws and corporate licenses that make sharing illegal); and supporting librarians who refuse to ban children’s books dealing with same-sex families. Pirate care can involve challenges to surveillance systems and algorithms used by bureaucracies.

Pirate care may involve providing meals to homeless people in Texas; supporting farmers who share seeds to grow food (in defiance of laws and corporate licenses that make sharing illegal); and supporting librarians who refuse to ban children’s books dealing with same-sex families. Pirate care can involve challenges to surveillance systems and algorithms used by bureaucracies.

The authors describe “an archipelago of self-governing initiatives, collectives, and coalitions operating within, outside, and across Empire’s enclosures and institutions” whose shared purpose is the organized provisioning of “plebeian care.” The book “aims to help pirate carers recognize themselves in their diversity and band together into a federation of mutually sustaining struggles that can turn the tide against an uncaring Empire.”

The very discourse of “pirate care” is useful, say Graziano and Medak, because it helps make compassionate care and social solidarity more culturally legible while pointing to a new type of political formation. The discourse also prefigures crucial theaters of struggle to come, and “builds our capacity to break free of Empire’s failing care regimes.”

For Graziano, Mars, and Medak, pirate care can be powerfully catalytic:

“Acts of renegade carers are reclaiming their capacity to make worlds. That’s why they are criminalized: the common wealth that they produce nourishes and propagates other forms of struggle.” As diverse forms of pirate care “multiply, diversity and connect, their collective power grows to more than the sum of its parts. The acts complement one another to make each one stronger. They thus allow for a revolutionary reclamation of society and its institutions.”

You can listen to my full interview about pirate care with Valeria Graziano and Tomislav Medak here. You may also want to check out a previous educational course, “Pirate Care Syllabus,” which provides extensive readings and resources on the topic.