The much-vaunted “energy transition” that promised a great leap forward from fossil fuels to renewables along with a cornucopia of technologies is now struggling with history and complexity. A few facts tell the story.

Despite all the talk of “decarbonization,” global coal production reached a record high in 2023. The dirtiest of fuels accounts for 26 per cent of the world’s total energy consumption. And despite all the promises of a green revolution, oil, gas and coal still account for 82 per cent of the global energy mix.

Meanwhile greenhouse gas emissions galloped to a new high in 2023. The concentration of carbon dioxide gases in the atmosphere has increased 11.4 per cent in just 20 years.

At the same time, the explosion of AI and data centres is now competing for new sources of electricity from renewables, methane and nuclear energy. That demand, some experts believe, will create an “insatiable demand for power that will exceed the ability of utility providers to expand their capacity fast enough.”

Unless we face such facts and make a dramatic course correction in how we behave and consume energy, we are surrendering human civilization to the vagaries of a prolonged climate crisis and the prospect of collapse. Given that a technical fix isn’t going to lower emissions on its own, isn’t it time to ask what kind of political, behavioural, demographic and economic transitions societies must consider to prepare for both climate chaos and limits to energy consumption?

Some clear-eyed experts are urging we rethink our response to climate change or face calamity.

One is French historian Jean-Baptiste Fressoz, who is not surprised by our seeming inability to replace and subtract fossil fuels with renewables that require fossil fuels for their construction.

‘The wrong way to frame it’

A green energy transition on the scale promised by global power brokers simply won’t happen, Fressoz says in his new book More and More and More: An All-Consuming History of Energy. In fact, he refuses to endorse the term green energy transition, calling the phrase a delusion and “a delaying tactic that keeps attention away from issues like decreasing energy use.”

In two recent interviews, one with nuclear advocate Chris Keefer on the podcast Decouple and another published on the site Resilience, Fressoz laid out his reasoning as well as our startling history of energy consumption.

The problem, explains Fressoz, is that humans don’t neatly shift from one energy source to another like marionettes. Nor do they march in lockstep from biomass to coal to oil to renewables like some robot army.

Evolving high-energy societies incorporate their old energy addictions into new ones to solve more problems. As a result, they consume more energy of any kind.

Transition is just “the wrong way to frame it,” says Fressoz. He has a different phrase to describe our dynamic energy state. He calls it “symbiotic expansion.”

It’s the basic idea that technological society exploits different forms of energy to accelerate flows of material goods. In the process, society adds more energy sources than it ever subtracts.

This history suggests that adopting material- and energy-intensive technologies such as carbon capture and storage or electric vehicles to battle climate change won’t achieve net-zero carbon by 2050, and that only a radical reduction in energy and material consumption might make a difference.

False energy tales of the past

Most schoolchildren and even the odd university student have heard the story about how the growing use of coal lowered demand of wood (biomass) for heat and thereby saved the forests. Indeed, biomass provided 98 per cent of energy for humans before 1800, but the tale is profoundly incomplete.

The advent of coal-fed furnaces and coal-powered steam engines did not conserve forests, says Fressoz. It merely repositioned the consumption of wood in the economy.

As the demand for coal increased, nations built more coal mines. And all of these new mines needed timbers to support the roofs and walls from caving in. Here’s a stunning fact: Fressoz calculates that coal mines actually used more timber for roof support in the 19th century than England burned in the 18th century.

“Forget the story about coal substituting wood. It didn’t happen that way.”

Now add the impact of steam-powered trains and the need for more tracks, which resulted in the consumption of 20 million cubic metres of wood for railway ties in the United States. That equalled 10 per cent of U.S. wood production in the 1800s.

“It is an entanglement of coal and wood that made the industrial revolution.”

Overall wood energy has fallen from 11 per cent of the world’s primary energy mix in 1960 to four per cent today. But consumption of wood has now reached an all-time global high (four billion cubic metres in 2022) thanks to chainsaws and feller-bunchers powered by oil.

“Raw materials and energy don’t go in and out fashion,” notes Fressoz.

The same can be said for oil. It did not replace coal but found new uses for it. In fact, every tonne of oil required 2.5 tonnes of coal to be extracted. The coal helped to make steel for pipes, trucks and wells needed for oil extraction.

“Instead of a transition we have a story of symbiotic expansion of energies.”

Meanwhile the oil industry likes to tell the story that its kerosene products helped to save the whales from extermination by eliminating the demand for whale oil for illumination.

But petroleum didn’t suppress the whale trade at all. It found new uses for whales (from corsets to lubricants) and actually accelerated the slaughter of whales thanks to fossil-fuel-powered ships that could catch more and larger whales more rapidly. As Fressoz notes, three times more whales were slaughtered in the 20th century than in the 19th century.

“The energy transition is a slogan but not a scientific concept,” explains Fressoz. “It derives its legitimacy from a false representation of history. Industrial revolutions are certainly not energy transitions, they are a massive expansion of all kinds of raw materials and energy sources.”

Others who echo Fressoz

Fressoz is not the first to make the dramatic assessment that faith in a green energy transition is misplaced because it ignores the complexity of the energy use (and its connections to everything) as well as the difficulty of designing a simpler civilization that uses fundamentally less energy.

The Australian geologist and mining engineer Simon Michaux has added up the sheer volume of metals and minerals needed to replace approximately 46,000 fossil-fuel-based power stations with nearly 800,000 renewable ones. His conclusion: there will be severe material shortages and bottlenecks to the extent that “the green transition will not work.” He proposes a total rethink.

Vaclav Smil, the noted energy ecologist, has also raised concerns about the sheer material intensity of renewables and the unsustainable demand for more materials.

The U.S. sociologist Richard York stated in a 2018 paper that the term “energy transition” is entirely misleading and counterproductive because history shows only a constant addition of energy sources over time.

“It is entirely unprecedented for these additions to cause a sustained decline in the use of established energy sources.”

York warned that the production of more renewable energy sources, due to their material intensity and poor energy density, would merely encourage more growth in energy consumption.

Nate Hagens, one of the world’s leading energy critics, has made similar observations in his Great Simplification podcast and presentations.

He notes that solar and wind are indeed growing rapidly and now make up 2.5 per cent of total energy consumption. The figure is probably closer to 5.6 per cent, according to the Energy Institute. But global fossil fuel production has grown by 21 per cent in the last 15 years.

“So far there has not been a green revolution, only a green addition.”

To further illustrate the point, Hagens notes that the use of biomass (animal dung and plants) is now greater today than it was in 1850 before petroleum. In fact, consumption of biomass has doubled since 1800. The conversion of wood matter into pellets (electricity generation) and packaging explains the dismal trend.

In fact, approximately six per cent of B.C.’s electricity on any given day comes from the burning of biomass. That’s more than wind or fossil fuels combined.

The late geologist Peter Haff made similar points but from a different perspective. He urged us to contemplate our entrapment within a “technosphere” of our own construction that acts as a parasite on the biosphere.

Haff explains that humans have used fossil fuels to construct a technological world dependent on a constant and growing supply of energy that appropriates rivers of materials to build complexity. Haff describes the technosphere as a largely autonomous phenomenon of which humans are mere components.

As a result, Haff doesn’t think the technosphere will tolerate a subtraction of energy sources.

“Whatever the future of particular renewable energy sources, the driving forces are already in place for transition to rates of energy consumption that are larger than, and perhaps much larger than, the current power level of fossil fuel use.”

The price of clinging to delusion

The Canadian energy analyst David Hughes adds another critical perspective.

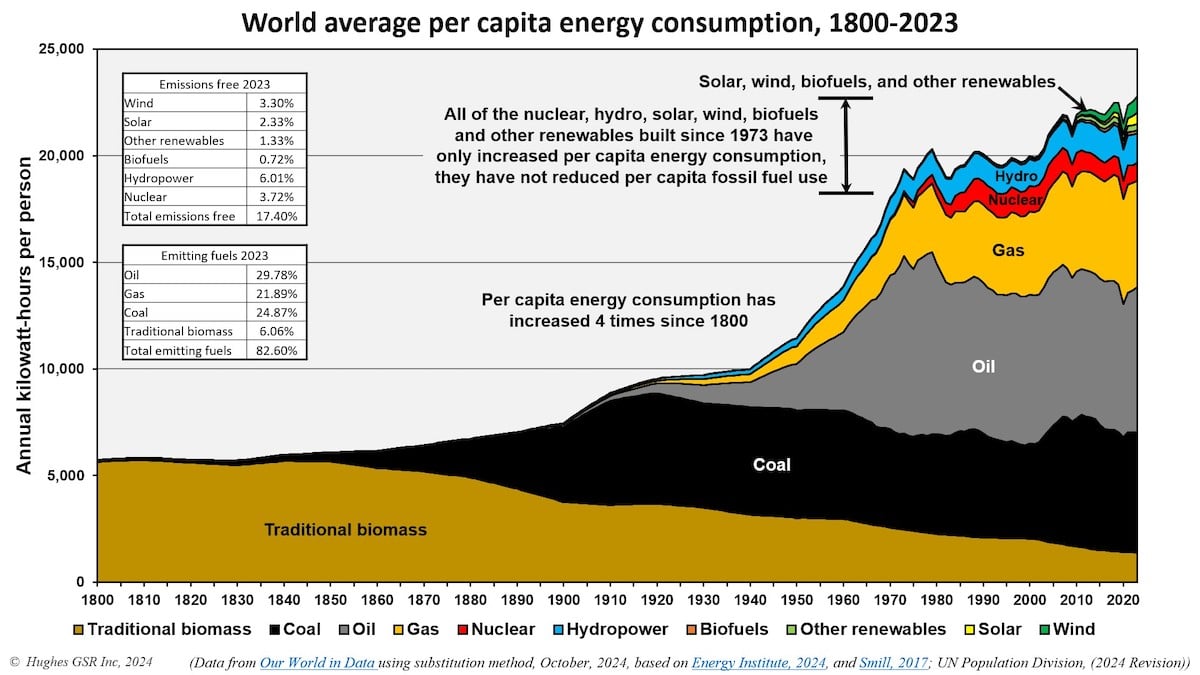

He soberly confirms that all the nuclear, hydro, solar, wind, biofuels and other renewables built since 1973 have only increased per capita energy consumption and not reduced per capita fossil fuel use.

Chart by David Hughes.

But he warns a dramatic change is coming whether it is planned or not.

“I would qualify Fressoz’s statement,” he told me, offering these bold-faced revisions: “An energy transition is unlikely to happen voluntarily, but an energy transition will most certainly happen, as fossil fuels are finite.”

He notes that industry cannot maintain current oil extraction rates for more than a decade due to depletion rates, and the increasing energy costs of producing poorer and poorer quality resources such as bitumen and fracked oil.

Global economies have been consuming more fossil fuels than they have discovered for decades, adds Hughes. In 2023, 10 barrels of oil and gas were consumed for every new barrel discovered, calculates the energy researcher.

Fressoz’s work and that of Hagens, Smil, Michaux and York also begs another question: Just where did the term “energy transition” come from? Fressoz provides a historical answer.

It actually originated with atomic scientists in the 1950s who were concerned about the depletion of fossil fuels and overpopulation. They imagined a utopian future in which nuclear energy might produce endless energy and desalinated water but not until the 23rd or 24th centuries. So the term “energy transition” really originated with nuclear engineers who envisioned a world totally propelled by breeder reactors.

Fressoz then asks a good question:

“How come this very strange futurology became the dominant futurology?”

“And there is a kind of, you know, scientific scandal, I think, that we recycled a notion, energy transition, which was supposed to take place in three or four centuries, and which was driven by the increasing price of fossil fuels… to climate change which is a completely different problem” and one that has to be addressed in three or four decades.

Fressoz offers no utopian solutions to our energy predicament.

He doesn’t think humanity’s habit of energy additions can be broken with unrealistic rhetoric about transitions. But the evidence on energy additions strongly suggests that communities must prepare to adapt to the climate storms now raging across the planet.

“And then we have to talk about sufficiency and degrowth. I think part of the aim of the book is to show that these topics, which have been completely neglected by economists… should be taken more seriously.”

Elizabeth Kolbert, the New Yorker journalist who has written about the science of climate change with wit and vigour for decades, recently concluded that climate change isn’t a problem that can be solved with “will.” Nor does she think it can be “fixed” or “conquered” for many of the reasons expressed by these critics.

“It isn’t going to have a happy ending, or a win-win ending, or, on a human timescale, any ending at all,” wrote Kolbert in H Is for Hope. “Whatever we might want to believe about our future, there are limits, and we are up against them.”

Or as David Hughes puts it:

“In summary, Mom Nature will take care of the coming energy transition if humans won’t.”