We’ve all heard the outrageously skewed statistics. The top 1%, or 0.1%, or even 0.01% of humans control an outsized fraction of total wealth (something like 30%, 15%, and over 5%, respectively). Because our culture values the fictional construct of money far more than is warranted, and the ultra-rich have a hell of a lot of it, they acquire status and access to power unavailable to almost everyone else. How can such a small fraction of the population possess such a disproportionate share of this resource—one that we’ve decided bestows influence and power? It doesn’t seem at all fair.

But, money isn’t the only disproportionate power-conferring asset on this planet. What else does our culture value above almost all else? Brains. What—are we zombies?! Large brains are what (we tell ourselves) set us apart from mere animals—taken to justify a sense superiority. Earth belongs to us. We can do whatever we want, because we’re the ones with the big brains: the self-declared winner of evolution—as if it’s even possible to have a winner in an interdependent community. Through innovation and technology development, we now wield god-like power over the rest of life on Earth—for a short time, anyway, until it becomes obvious that “winning” translates to “everybody loses.”

Given our similar tendencies to overvalue money and brains, I was motivated to compare inequality in brain mass within the community of life to the gross inequality we abhor in financial terms. Is it as bad? Worse? Humans constitute 2.5% of animal biomass, and 0.01% of all biomass on the planet. We are also one of perhaps 10 million species, which in those terms means we represent only 0.00001% of biodiversity. Any way you slice it, we are a small sliver of Life on Earth—while managing to dominate virtually every ecological domain. As our culture tells it, humans are the deserving elites.

What fraction of the planet’s brain wealth do we possess? To be clear, in performing this analysis, I am not making the case that brains are what matters—far from it. But in our culture, our brains are cherished and essentially worshiped for their unique capacity in terms of ingenuity, allowing us to defy the limits that all other species “suffer.” What is our disproportionate share of brain mass? Is it as bad as 15% or 30%, like our egregiously-lopsided wealth inequality?

For this exercise, I rely on biomass assessments by Greenspoon at al. 2023 (mammals) and Bar-On et al. 2018 (all life), as well as scattered data I could pick up on brain masses, body weights, etc. I was moderately careful, but not excessively so, as the purpose is not precision but illustration in an approximate sense. I got a result that at least helps me put things in context—better than I could do on a guess.

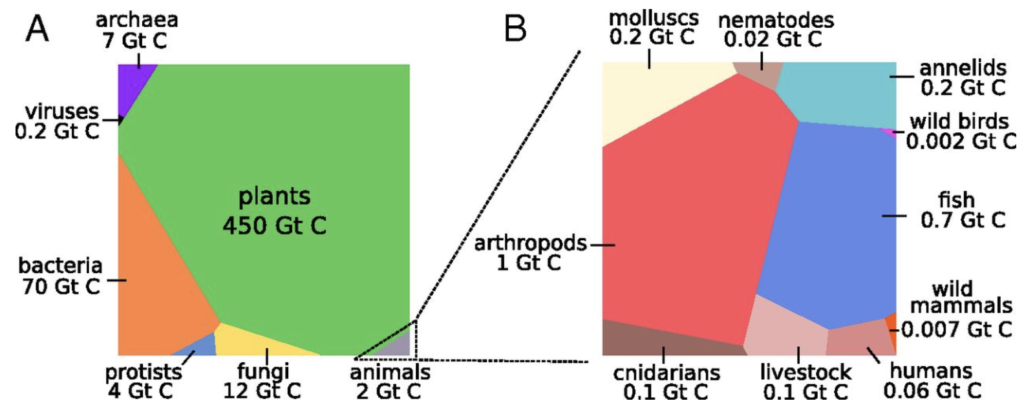

Dry carbon biomass on Earth, from Bar-On et al. 2018. Wet mass is roughly 7 times larger.

Humans

We start, as we are wont to do, with our supreme selves. Greenspoon et al. have human “wet” biomass at 394 Mton (mega-tons; metric). Call it 400 Mton (it’s still growing, after all). That’s 8 billion people at an average of 50 kg apiece. The entire mammal population on Earth, including humans of course, sums to 1080 Mton according to Greenspoon et al., so that humans amount to about 36% of mammal biomass.

Human brains are typically about 1.4 kg, so that we’re dealing with about 11 Mton of brain mass. I’ll switch to kilotons for easier comparisons, so that’s 11,000 kton. At this point, feel free to skip to the Summary Table if you don’t care for the nitty-gritty that follows.

Domesticated Mammals

Greenspoon et al. provide a table of domesticated mammals (in the supplement). I folded in some crude estimates of individual mass to get population counts, and added brain mass, resulting in the following table. In this table and the ones that follow, the total (wet) biomass of each species or group is given (in megatons), the number of individuals (population) in millions, approximate brain mass of an individual, in grams, and the total brain mass of that species, in kilotons.

| Category | Mton | Pop. (M) | brain (g) | total brain (kton) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cattle | 416 | 830 | 450 | 375 |

| Buffalo | 68 | 140 | 450 | 61 |

| Sheep | 39 | 560 | 140 | 78 |

| Swine | 38 | 380 | 180 | 68 |

| Goats | 32 | 800 | 130 | 104 |

| Dogs | 22 | 1,500 | 72 | 106 |

| Horses | 16 | 40 | 700 | 28 |

| Camels | 8 | 16 | 600 | 10 |

| Asses | 7 | 18 | 370 | 6 |

| Cats | 2 | 330 | 30 | 10 |

| Camelids | 1 | 2 | 600 | 1 |

| Mules | 1 | 2.5 | 190 | 0.5 |

| Rabbits | ~1 | 170 | 10 | 1.7 |

| Rats | ~1 | 2,300 | 2 | 4.5 |

| Mice | ~1 | 36,000 | 0.4 | 14 |

| Total | 650 | 870 |

Please do not mistake these for definitive numbers. They’re good enough for this very approximate exercise, but not to be taken as authoritative.

The total mass of domesticated mammals outweighs even humans—representing nearly 60% of mammal mass on the planet—while total brain mass in this grouping is about 13 times smaller than human brain mass. How’s that for a stoking a smug sense of superiority? It just gets more extreme as we continue.

Land Mammals

Adding up to a mere 20 Mton (wet), the wild land mammals are highly varied, so that only about 45% are represented in the top ten list provided in Greenspoon et al. Here’s their table, amended with brain data.

| Category | Mton | Population (M) | brain (g) | total brain (kton) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White-tailed deer | 2.7 | 45 | 200 | 9 |

| Wild boar | 1.9 | 30 | 180 | 5.4 |

| African elephant | 1.3 | 0.5 | 4,800 | 2.4 |

| Eastern gray kangaroo | 0.6 | 20 | 35 | 0.7 |

| Mule deer | 0.5 | 7 | 200 | 1.4 |

| Moose | 0.5 | 1.5 | 120 | 0.2 |

| Red deer | 0.5 | 2 | 200 | 0.4 |

| European roe deer | 0.4 | 20 | 200 | 4 |

| Red kangaroo | 0.4 | 1 | 56 | 0.6 |

| Common warthog | 0.3 | 5 | 120 | 0.6 |

| Total | 9.1 | 25 |

First, note the drop in scale compared to previous numbers: this is itself of huge concern, leading to the fact that only 2.5 kg of wild land mammal mass remains per human on the planet: almost gone! But once getting over that shock, we calculate 25 kton of brain mass while capturing 45% of total wild land mammal biomass. So, I apply a simple scaling correction to arrive at a total brain mass of 55 kton for wild land mammals. This likely results in an underestimate, as smaller mammals tend to have a higher fractional brain mass, but we’re probably not off by more than a factor of two, which in any case hardly makes a dent in the running total. Remember: these numbers need not be at all precise to make an overall point.

Marine Mammals

At roughly twice the biomass of wild land mammals—40 Mt—we might expect roughly twice the total brain mass for marine mammals (especially given how smart dolphins and whales are). But whales are huge, and the scaling works out so that fractional brain mass is smaller. In any event, the following table tracks what happens. Note that I have thrown in an extra line for dolphins as a group.

| Category | Mton | Population (M) | brain (g) | total brain (kt) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fin whale | 8 | 0.1 | 6,900 | 0.7 |

| Sperm whale | 7 | 0.4 | 7,800 | 3.1 |

| Humpback whale | 4 | 0.1 | 4,700 | 0.5 |

| Antarctic minke | 3 | 0.5 | 2,700 | 1.4 |

| Blue whale | 3 | 0.05 | 7,000 | 0.4 |

| Crabeater seal | 2 | 10 | 500 | 5 |

| Bryde’s whale | 1.3 | 0.1 | 5,000 | 0.5 |

| Common minke | 1.3 | 0.2 | 2,700 | 0.5 |

| Harp seal | 1.2 | 10 | 400 | 0.4 |

| Bowhead whale | 1.1 | 0.05 | 2,700 | 0.14 |

| Dolphins | 3 | 20 | 1,650 | 33 |

| Total | 35 | 49 |

Accounting for 87% of the total marine mammal biomass in these eleven entries, we need only a small correction to the total brain mass to arrive at 56 kton of marine mammal brain mass—basically identical to the estimate for wild land mammal brain mass, despite twice the total biomass. The economy of whale scale is a hefty part of that story.

Birds

Wild birds amount to less than 0.1% of animal biomass—about 30 times smaller than human biomass, and roughly half that of wild land mammals. I had a harder time tracking down specifics (and was running out of steam to be honest), so I take a bit of a punt, here. The most impressive bird thinkers, like ravens and parrots can have 2% of their body mass in brain form. Guessing an average of 1% across the birds (which comes out high compared to mammals, but okay for smaller creatures) and applying to approximately 13 Mton of bird biomass results in 130 kton of bird-brains. That’s about double wild land mammals for half the mass. Given the uncertainty, I’ll round to 100 kton, but feel free to rework the conclusions with your own number if you don’t like mine (hint: nothing substantive changes).

Domestic birds—dominated by chickens—have a biomass exceeding wild birds by a factor of 2.5, amounting to one-twelfth of human biomass. That’s 33 Mton (wet), translating to about 10 billion chickens. Raisin-sized chicken brains are 2.6 grams, resulting in about 30 kton of chicken brain.

Reptiles and Amphibians

Bar-On et al. characterize the biomass of both these categories as “negligible” among animals. That, together with small-ish brains, leads me to ignore the contribution here, which would no doubt hardly register against the foregoing numbers.

Fish

Fish, however, constitute almost 30% of animal biomass, and they do have brains, however quaint. A shark’s brain is only about one-three-thousandth its body mass, which is 100 times smaller than humans relative to body mass. But the vast oceans contain many fish, and the brain’s fraction of body mass tends to increase as fish get small and numerous.

I also punted on this one, but found two sources of value (here and here), from which I gathered that the biomass distribution of fish is roughly equi-partitioned: similar total mass in each logarithmic mass bin. That means ten times as many individuals between 0.1 and 1 kilogram as between 1 and 10 kg, but amounting to the same total mass. The other piece quantifies the rate of increase of fractional brain mass as fish get smaller. What I find is that the fish in the 10–100 kg range contribute about 150 kton of brain mass; the next decade down 400 kton; then 1,000 kton, followed by 2,000 kton for fish between 10 grams and 100 grams. The next tranche of tiny tots (1 to 10 grams) has about 7,000 kton. It adds up: lots of fish in the sea thinking about seafood, or how to avoid being seafood. The net result is comparable to human brain mass, at about 11,000 kton—very approximately.

Non-Vertebrates?

I stopped at the vertebrates. A cursory look at insects (arthropods being substantial, at 40% of animal biomass) tells me that their aggregate brain mass may add up to numbers comparable to humans and fish. Ants alone, for instance, amount to 20% of human biomass and have fractional brain masses around a few percent, contributing something like 2,000 kton to brain mass totals.

But I don’t really know what I’m doing here. For instance, should I count worms? Do brain stems count? In our wealth analog, worm and insect brains are almost like an unrecognized currency, unavailable for exchange. People in comas are not valued in our society for their innovative capabilities, or even tested in experiments like ravens or mice might be. Since I’m trying to track attributes that humans of modernity value, my strong sense is that it’s more about the cerebral cortex than the portions that maintain bodily functions. Maybe I should be subtracting out brain stem mass, and perhaps even cerebellum. This is well outside the scope of a weekly blog post. While insects (ants, bees, beetles, etc.) obviously have more going on than just bodily functions, it might be most appropriate to just consider mammals and birds in our comparison (sorry, fish). There’s no correct way to do this, so let’s focus more on what we can learn than on the elusive goal of getting it “right.”

Summary Table

It’s worth collecting the foregoing (approximate) numbers in one place so that we might put the matter into perspective.

| Category | Brain mass (kton) |

|---|---|

| Human | 11,000 |

| Domestic Mammals | 870 |

| Wild Birds | 100 |

| Wild Land Mammals | 55 |

| Marine Mammals | 55 |

| Domestic Birds | 30 |

| Reptiles & Amphibians | — |

| Fish | 11,000 |

Comparisons

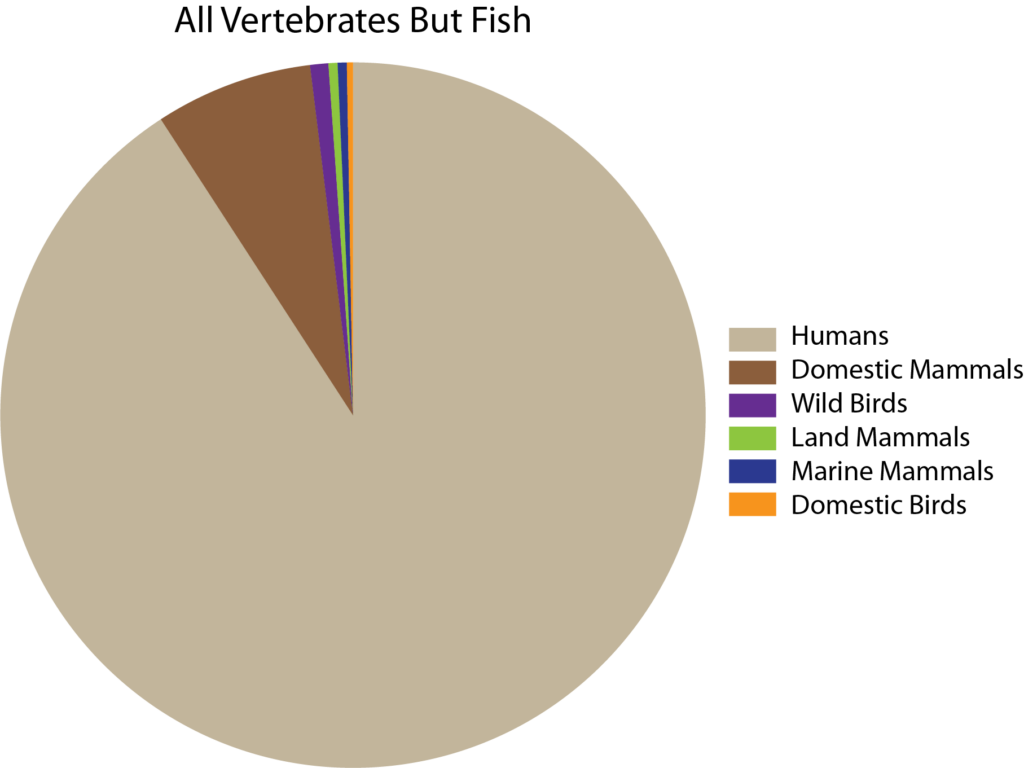

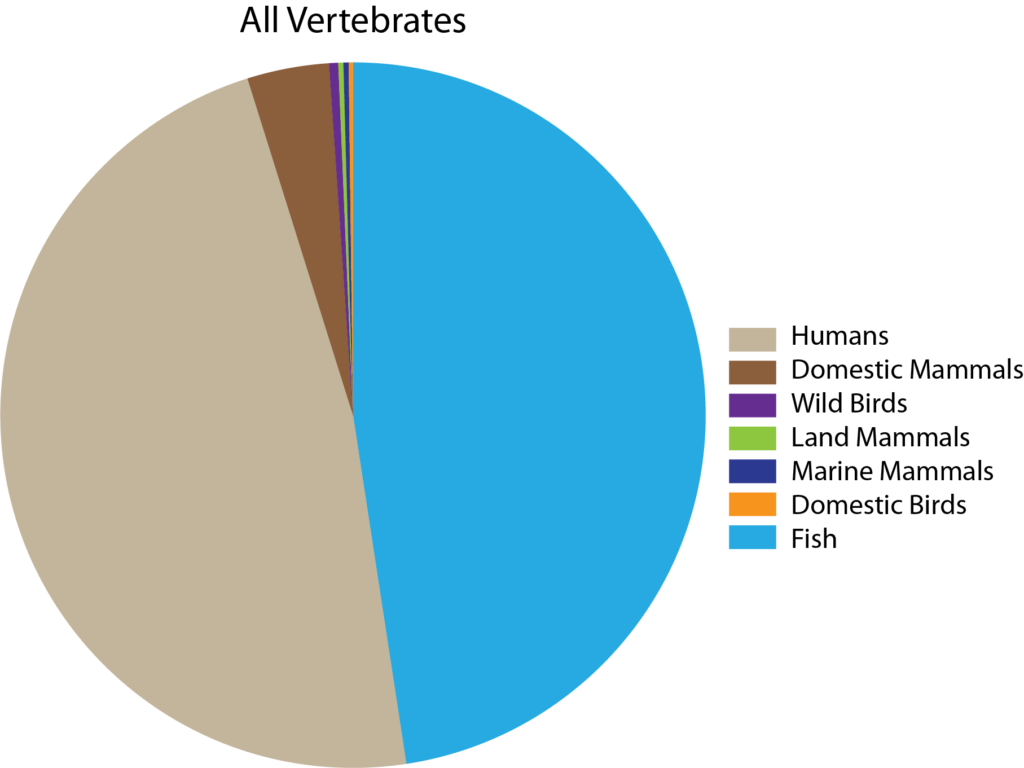

Depending on how one considers fish—which carries a similar ambiguity for some vegetarians—the assessment looks different. The first notable outcome is that a single species (humans) tops whole categories, and even when including fish account for roughly half of vertebrate brain mass on Earth. But let’s first look at the fish-free comparison.

Reptiles’ and Amphibians’ contributions are too small to see here.

Among mammals, humans hold 92% of brain mass. That means one species out of 5,000 (thus the “top” 0.02%) hogs 92%. Adding birds hardly changes the number (91%). By comparison, in financial terms the wealthiest 0.1% hold “only” 15% of the loot. Looking at the other 99.9% of mammal species, wild land mammals and marine mammals each cling to only about 0.5% of mammal brain mass, making them the poorest of the poor—but wait: we haven’t even gotten to the enormous bulk of life having no brains at all. Are we to consider them more poorly than the poor? Worthless?

Reptiles’ and Amphibians’ contributions are too small to see here.

Among all animals, 2.5% of the biomass (humans) claims nearly 50% of brains (now including fish). Among all life, humans represent a 0.01% slice by mass or 0.00001% by species, while holding almost half the brain mass. And you thought wealth inequality was bad. Compare these results to the top 0.01% of wealthy individuals hoarding 5–7% of wealth. Brain inequality blows financial inequality out of the water!

What of it?

I am aware that a number of readers might think: well, good on us: more proof of human supremacy. Careful there. Assertions of physiological superiority have a dark history (and present). In financial terms, just imagine the billionaire being pleased with the lopsided nature of his wealth—serving to prove how remarkable he is. (I’m casting the billionaire as a man because these jerks usually are…) Imagine the justifications that are possible for the billionaire who sees his wealth accumulation as validation of intrinsic greatness. How is it any more acceptable when it comes to brain discrimination?

Read the following statements in two parallel ways: a billionaire discussing a poor person, and a human discussing a lifeform lacking brains—like a particular species of paramecium, lichen, spurge, or jellyfish:

They are nothing to me. I might find ways for them to be useful to me, but I doubt it. They are dispensable. They could disappear from this earth and newspapers won’t report it. They neither have nor deserve the power I possess. Only I and my ilk can make the world a better place, accessing tremendous assets. Because the lower classes don’t have the capacity (or luck) to be graced with my resources, that’s just tough for them. How would such a being even be capable of appreciating its plight when they never have and never could experience life as I know it? I deserve to be on top of the heap, and I’ve got the money/brain to prove it.

Give it some consideration: are you a brainist (parallel construction to racist)? Do you believe our brains give us special privileges and justify any action we find convenient to ourselves—no matter the cost to life without brains, or to those with inferior cerebral hardware? Are other species nothing to us except utility—and even then only in some cases? Might such an attitude contribute to the initiation of a sixth mass extinction that we now witness? Might a sixth mass extinction also seal the fate of a large, hungry, complex, high-maintenance mammal? Will it somehow favor metabolically-costly large brains, or will we find it to be unsympathetic to our own admiration?

Beyond Brains

There’s a lot more to life than brains. Note that we share a third of an amoeba’s genes, regulating many of the critical nuts-and-bolts functions of our cells. We share 60% of a banana’s genes. Only 0.5% of biomass is in animal form, and not even all animals have neural centers that qualify as brains. Yet, that tiny sliver of life boasting brains could not exist without the much larger and more diverse (spectacular) brainless web of life existing alongside. Because many of these species have been around much longer than us, they know more than we do where it counts. Their knowledge might not be processed by neurons in a cerebrum (a recent trick), but is still unquestionably present and robust. Brains are just one way of knowing, and not the dominant one, or longest-lived one, in fact.

Consider also your own body, where perhaps 2–3% of your mass is brain meat. Yet the brain would be a useless lump without the heart, lungs, kidneys, stomach, pancreas, and all the rest. There’s much more to being human than having a brain, and much more to life on this planet than the few species that happen to utilize the brain adaptation.

Humans hold up brains as the most important attribute. Is it a coincidence that this just happens to be our most heavily-invested niche, in evolutionary terms? What would a bat think defines excellence? What would a snail define as the ultimate quality, or a barnacle? Silly goose: these animals don’t bother defining anything at all (a cerebrally-biased habit of questionable value), and are arguably better ecological citizens for it.

Don’t Let it go to Our Heads

My main point is: just as our culture misplaces value in money, we misplace value in brains—in a transparent display of ugly self-flattery. We’re the insufferable billionaires of the brain sector. Human brains are a very new experiment on the planet, which appears to be driving a sixth mass extinction, presently. Time to reign it in. Let’s not double-down and soothe ourselves with empty stories that we can solve any of our mounting problems (of our obvious unwitting creation) with more brain-driven innovation and technology (brain-farts, as I’ve taken to calling them).

Now, are our brains capable of self-deprecation, or did evolution produce an organism only just capable enough to produce great harm but not capable of self-limitation? Well, some cultures deliberately crafted self-restraining customs and stories, so I don’t believe we can rule out living responsibly. If we are to succeed for the long term, it won’t be in a style that looks like modernity, but will most likely have great overlap with the ways of other beings who have proven their longevity on this planet. Rather than exalting brains and our thoughts, a successful human culture will be suspicious of where these narcissistic, unconstrained, decontextualized shortcut machines might lead us, if left unchecked.