I gave a talk on collapse earlier this autumn to the community of futurists that is co-ordinated by DEFRA, the British government’s Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs. It was based on an article I wrote earlier this year, and discussed here in March. The presentation slides are linked at the end of this post.

One of the things that popped up in the chat while I was talking immediately caught my attention, given my interest in long waves and futures. It was an article by Luke Kemp and colleagues at the BBC Future website that discussed the timespans of states, and their patterns of decline. 200 years is about the average, which tallies with the 100-300 year window used by Peter Turchin and his colleagues working on ‘secular dynamics.’

Perhaps this isn’t surprising since Turchin draws on the Seshat model, which Kemp and his colleagues use as one of their sources.

Signs of decline

Thinking about civilisations as being time-limited immediately leads you to a particular perspective about them, which is in effect, that as civilisations age they are more likely to show signs of decline, in the same way that we can make the same kinds of assumptions about people.

And from that, of course, we can start to build a view of what those signs of decline might be. But I’m getting ahead of myself here. Let me go back and discuss their approach to research and analysis first.

Luke Kemp is a research associate with the Notre Dame Institute for Advanced Study, and a research affiliate with Cambridge’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk.

Pre-modern societies

The research here is into pre-modern societies, since if you are measuring how long they have lasted for you need to know that they have come to an end. They restricted their analysis to”states”, which they defined as organisations that enforced rules over a given territory and population.

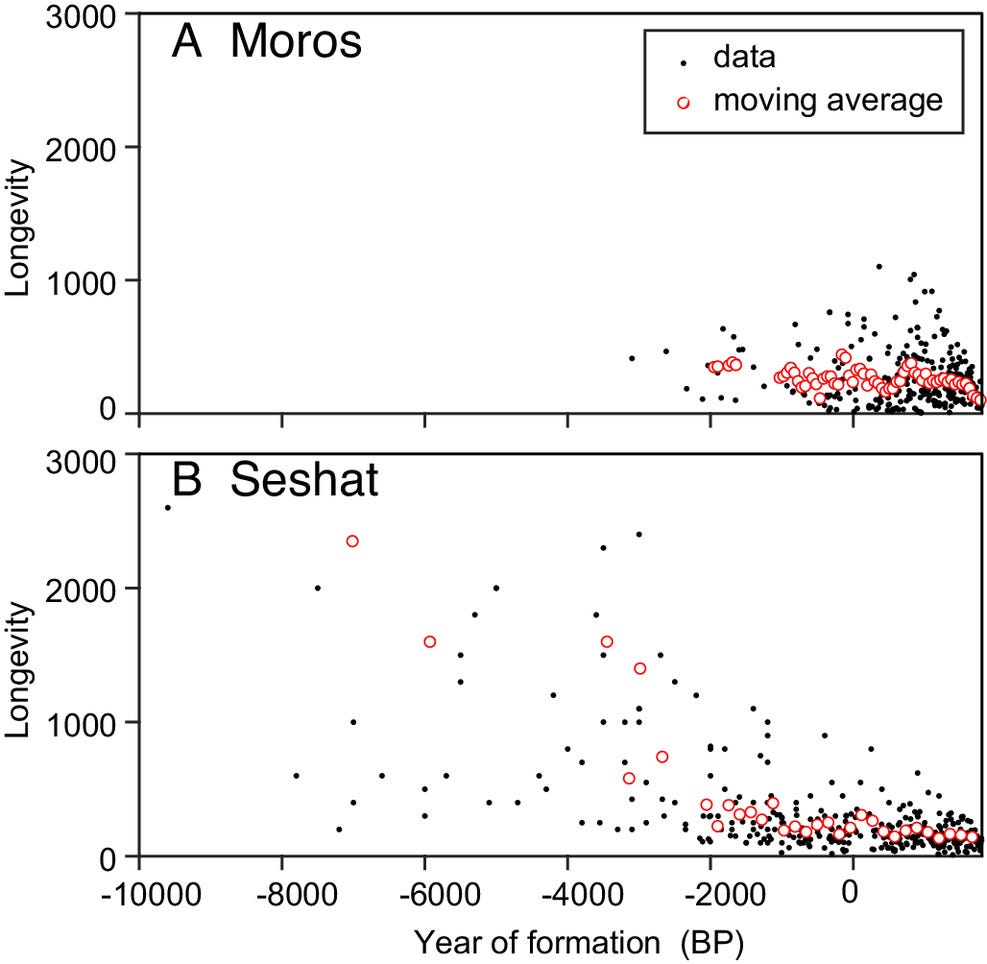

To collect data, they created their own database, called MOROS, which “contains 324 states over 3,000 years (from 2000BC to AD1800).” The data was assembled from other databases, an encyclopedia on empires, and so on. MOROS, by the way, is the Greek God of Doom. Academics are such wags.

As mentioned above, they also consulted Seshat, which has been curated over time by archaeologists and contains data on 291 polities. (Seshat? The ancient Egyptian goddess of wisdom, writing, and knowledge.)

(‘The longevity of societies plotted against their year of formation for (A) the MOROS database and (B) Seshat database. Red circles are means for time windows each covering 1% of the data’.[1] Source: Scheffer et al.)

‘Survival analysis’

The two datasets, in other words, produce similar results. To do their research, they used a technique called “survival analysis”, which analyses the spread of lifespans:

If there is no ageing effect, then we can expect an “ageless” distribution in which the likelihood of a state terminating is the same at year one and 100. One previous study of 42 empires found exactly this. In our larger dataset, however, we found a different pattern. Across both databases, the risk of termination rose over the first two centuries and then plateaued at a high level thereafter.

This, apparently, is a similar finding to another recent study that found—in an analysis of historic crisis events—that the average polity had a life of 201 years.

In the academic article they summarise their findings like this:

In conclusion, the distribution of longevities reveals that the risk of termination rises over the first two centuries, and then remains roughly constant. That is, newly established states appear to have some benefit of youth in terms of survival chances, but this effect fades away over the first ~200 y[ears].

‘Critical slowing down’

In other words, as you approach 200 years, the risk of termination increases, but if you get past 200, the risk of termination flattens out. One of the effects of ageing is that societies recover more slowly from disturbances. This is known in the systems literature as “critical slowing down”, and is seen across many different types of system:

Before a complex system undergoes a large-scale shift in structure, or a “tipping point”, it often begins to recover more slowly from disturbances. The ageing human body is similar: injuries can take a longer toll when you’re older.

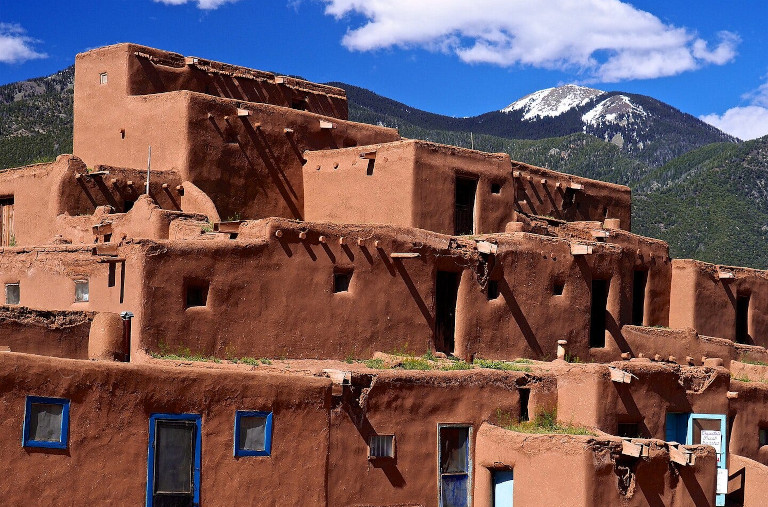

The point is that “critical slowing down” is an indicator of loss of resilience. The article discusses two examples of this from the archaeological literature—neolithic farmers in Europe and the Pueblan societies in what is now the south-western United States. Taking the second of these:

The Pueblo societies were maize farmers who erected the largest non-earth buildings in the US and Canada before the metal-framed skyscrapers of Chicago in the 1800s. The Puebloans also underwent several cycles of growth and contraction, ending with crisis events in around AD700, 890, 1145, and 1285. During each of these events, population, maize, and urbanism fell, while violence rose. On average, these cycles took two centuries, in line with the wider pattern we found.

(Taos Pueblo building in New Mexico. Photo: John Mackenzie Burke, CC BY-SA 4.0)

(Taos Pueblo building in New Mexico. Photo: John Mackenzie Burke, CC BY-SA 4.0)

State termination

In each cycle, recovery from crisis was slower than in the previous crisis.

Of course, there are some caveats here. One is the definition of a “state termination”. These take multiple forms, from a new ruling elite to a full-scale collapse, in which there is loss of government, written records, shared institutions, and population decline.

In addition, state termination may not be a bad thing. In some cases, state collapse led to greater prosperity for the majority:

Many pre-modern states were grossly unequal and predatory. By one calculation, the late western Roman Empire was three-quarters of the way towards the maximum level of wealth inequality that is theoretically possible (with one individual holding all the surplus wealth).

(By the same score, I’d note that the elite coup d’etat in England—later repackaged as the “Glorious Revolution”— that engineered the replacement of James II by William and Mary definitely led to an upturn for the English state.)

Longevity factors

The numbers are also based on generally accepted start and end dates, which may not be completely reliable, given their distance in history. Even more recent state terminations can be problematic. Constantinople fell in 1453 to the Turks, but it was also partitioned in 1204 by marauding Crusaders. (I’d imagine they might both be terminations, although the 1453 one was rather more final.) The researchers deal with this by providing a range of estimates.

Their next steps in their research will be to examine the factors that create longevity.

States could be losing resilience over time due to variety of factors. Growing inequality, extractive institutions, and conflict between elites could heighten social friction over time. Environmental degradation could undermine the ecosystems that polities depend on. Perhaps the risk of disease and conflict rises as urban areas become more densely packed? Or loss of resilience may be due to a combination of different causes.

Cascading effects

Depressingly, both extraction and environmental degradation are seen in the collapse literature as causes of collapse, along with over-complexity.

Of course, modern states are not the same as pre-modern states. They are more complex and more connected. But that may not reduce their vulnerability; it may just mean that they are at greater risk of collapse or termination from cascading systemic effects. We barely need to rehearse the litany of crises, from climate change to global wealth inequalities to failing planetary boundaries to the plethora of powers with nuclear weapons:

[T]he instability of a superpower, such as the US, could trigger a domino effect across borders. Both Covid-19 and the 2007-2008 global financial crisis have shown how interconnectivity can amplify shocks during times of crisis. We see this in many other complex systems.

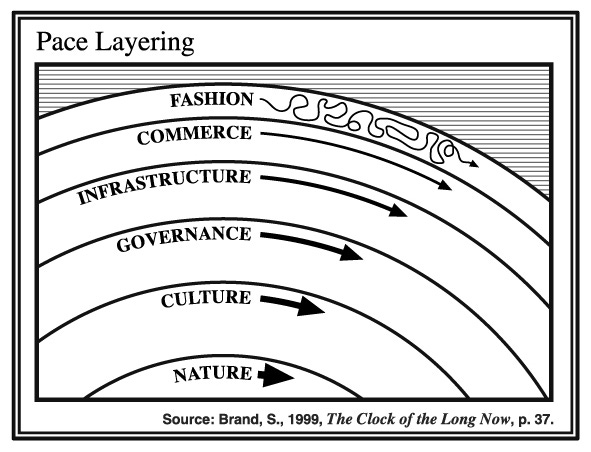

(Source: The Long Now Foundation)

The Governance layer

But one of the things this research allows us to do is to attach a number to one of the layers in Stewart Brand’s pace layers model, which when discussed is largely conceptual. As a reminder, the top three layers are the ‘fast’ layers, the bottom three ‘slow’ layers.

Fast learns, slow remembers. Fast proposes, slow disposes. Fast is discontinuous, slow is continuous… Fast gets all our attention, slow has all the power.

In other words, the top three are sources of innovation, the bottom three sources of stability. Governance is the fourth layer down. We can assume now that the Governance layer has a clock speed of around 200 years.

The Collapse presentation can be downloaded here.