Four years from now Vice President Kamala Harris may be glad she didn’t get the promotion she was seeking from the American electorate. In fact, all those vying for high office around the world may find that the going from here on out will be much more difficult. What few of them realize is that global society has not only become a version of the Titanic, but that we’re at the place in the story where the Titanic has already hit an iceberg.

Of course, government leaders around the world generally believe that—whatever our current troubles—the technological progress of humanity will continue unabated and our lives will get better. The world system we’ve created is, well, unsinkable. At least that is what they are conveying to voters; politicians generally know better than to suggest that under their watch people are going to have to make sacrifices. The last politician to do that was U.S. President Jimmy Carter and he was defeated for re-election.

Carter seemed to understand that we live in an age of resource limits and was attempting to prepare us for the necessary transition. But Americans didn’t want to turn down the heat and wear sweaters indoors; they preferred gym shorts and T-shirts instead. Thirty-six years after what came to be called Carter’s “Malaise Speech” one writer opined that “President Carter made the unforgivable error of treating the American people like adults.”

The rumbling social and political discontent that is spreading across the globe and toppling long-established ruling parties is what one would expect in the face of diminishing opportunities resulting from diminishing resources. Energy prices are considerably higher than they were when Colin Campbell and John Laherrère announced in the March 1998 edition of Scientific American that we would soon face the end of cheap oil.

The price of oil bottomed out near $10 a barrel in December that year and then rose inexorably to an all time high in 2008 of $147. Though lower today, it remains much higher than it was in 1998, even adjusting for inflation. (Using the inflation calculator of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, $10 in December 1998 is equivalent to $19.26 today. Brent crude futures for February 2025 closed at $71.84 on Friday. Brent crude futures are a widely used world benchmark for oil prices.)

Worth mentioning is the fact that world crude oil production (defined properly as crude oil including lease condensate) topped out in November 2018 and has failed to reach that level again. Also, worth mentioning is that oil still provides the largest share of energy from any source to our global society.

Coal and natural gas rose relentlessly as well in the price run-up of the 2000s. The natural gas price is now depressed in the United States due to overproduction by natural gas drillers, but has skyrocketed in Europe due to war-related cutoffs of supply from Russia. Coal prices are high and highly volatile. Uranium, too, is finding a new higher level (click on “All” to see the entire available price history).

Energy isn’t the only resource limit we are facing. Many key minerals will be difficult to obtain in the quantities we’ll need for the so-called energy transition. Fresh water suitable for drinking and agriculture is already strained. And lack of water, both in the form of rain and irrigation, spells trouble for food and fiber crops. There is, of course, a driving force behind water and food issues, climate change—something which many aspiring and now current leaders are denying is a real problem.

And that takes us back to the “unsinkable” meme which has practically the entire globe in its thrall. Recent winning political rhetoric suggests that governments just have to be downsized to bring better days ahead. In Argentina, the new prime minister—who campaigned with a chainsaw at his side to demonstrate his willingness to cut what he called bloated government spending—has managed to drive the country into severe recession with cuts that are increasing poverty and unemployment. In the United States the incoming Trump administration has said it will cut $2 trillion from the annual federal budget. Of course, neither program of cuts does anything to address the critical underlying problems we face—except perhaps by reducing economic activity temporarily which reduces demand for resources.

Rather than merely rearranging the deck chairs on the Titanic—by, say, shifting expenditures around—Argentina and now perhaps the United States propose to do the equivalent of throwing lots of deck chairs into the Atlantic and hoping that will right the ship of state. But these and other ships of state will continue to take on water as they sink into the ecological and resource depletion gyre we humans have created.

Perhaps least understood is the financial fragility engendered by attempts to prop up consumption to keep the unsustainable party going. The vast ongoing worldwide credit bubble—the “everything bubble”—is a reflection of the desire to maintain economic growth in the face of considerable headwinds (both environmental and technological) by bringing future consumption forward.

It is important to understand that credit is a call on future energy production for energy is at the base of everything we produce and consume. If the energy is not there in sufficient quantities, sufficient production will not occur, and the creditors will not be paid back, at least not in full. When markets finally adjust to this reality, much of current credit will disappear and those advancing credit will become much, much more selective about who gets it. The result will be a financial crash, almost certain to be worse than 2008. (For why we are facing technological headwinds—despite all the blather from our tech overlords—see The Rise and Fall of American Growth, much of which applies to the rest of the world.)

It is being repeated again and again that the high price of food determined the recent American election outcome. It is a colossal failure of civic education that many American voters believe the president of the United States can over his or her short term have a significant effect on the price of food. There are so many other variables.

But if we look specifically at the problem of high egg prices more closely, we can see the equivalent of water flowing into the Titanic ship of state. Bird flu is taking its toll on egg-producing bird flocks—it kills lots of birds—leaving fewer to lay eggs. And, the rapid spread of bird flu is a result, in part, of two things: 1) the worldwide transportation of goods, services, people and animals in our globalized system of commerce and 2) the factory farm conditions under which most eggs are produced—birds are jammed together in confined spaces and thus more likely to transmit disease.

Factory farms are something the president might be able to do something about through the U.S. Department of Agriculture. But the solution might actually drive prices up by forcing egg producers to give chickens more room to roam and cleaner conditions to live in. In short, we’d need to go back to ways of animal husbandry that would raise prices, but reduce disease and risk of transmission to birds, humans and other animals.

But there’s another huge problem posed by the rapid and relentless spread of bird flu. The disease could mutate into a form that would spread easily from human to human. So far, the recent cases of bird flu in humans appear to come from contact with animals and they have largely been mild. But past human cases contracted from animals have had a high mortality rate approaching 50 percent. (That’s NOT a typo.) If the bird flu mutates into one transmissible by humans, one former director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention believes mortality rates could hit 25 percent. That’s at least 25 times higher than the U.S. mortality rate for COVID-19.

Whoever presides over such a pandemic caused by this or another yet-to-be identified microbe will certainly end up being blamed for an inadequate response. But any response that would actually reduce the likelihood of a serious pandemic BEFORE it happens would involve a wholesale decentralization and deglobalization of the economy and our society (which would reduce international transmission across borders and oceans). Another important response would be to make people healthier (and thus more resistant to disease) through much healthier diets (read: far less processed food), removing toxic chemicals from the air, water and soil, and emphasizing regular physical activity. And, no top world leader I’ve read about appears ready to embrace such solutions.

There are so many other resource and environmental problems that can’t be solved by continuing business-as-usual. The leaders whom voters are putting into office now out of anger or disappointment (much of it justified) will likely just stand at the bow of our Titanic and tell us they can see a passage to calm, ice-free waters ahead. Whatever their programs—whether they are considered rightist, leftist, or simply crazy—those programs almost certainly won’t change the trajectory of the ship which is down into the depths rather than forward.

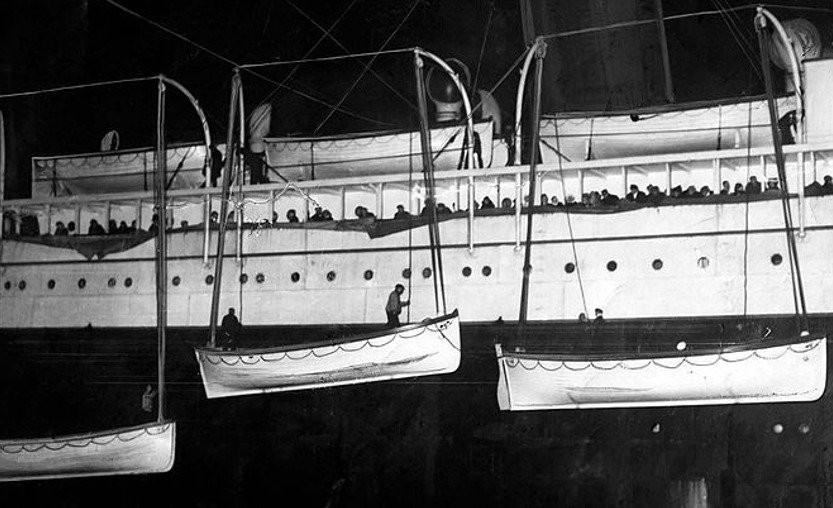

It is instructive to review a lesser known tragedy within a tragedy regarding the sinking of the Titanic. Only 706 people survived in lifeboats when the capacity was 1,178. Apparently, the crew mistakenly believed that the davits (the cranes for lowering the lifeboats into the water) would not withstand the strain of fully-loaded lifeboats. So, the crew loaded fewer passengers before putting the boats in the water. The crew, it turns out, had not received updated information before the voyage.

We humans, our businesses and our governments are not even affording ourselves all the known lifeboats available to us—that is, policies and practices that could lessen the consequences of resource and environmental limits—because most of us believe our global society is unsinkable. Beware of those who say I’m being too alarmist. They will not offer you a warranty on their promise that all will be well, a warranty that would give you your life and our planet back in good condition should our current trajectory turn out of be disastrous. Inquire into why those critics are so adamant that technology will save us. Could it be that they represent the very technology and thinking that is failing us?