This story was originally published by Barn Raiser, your independent source for rural and small town news.

Iowa’s environmental crisis has policy leaders and farmers challenging corporate agriculture.

At 84, former Iowa Sen. Tom Harkin is still showing his capacity as an unlikely reformer.

Harkin retired from the U.S. Congress in 2015 after 30 years as a Democratic Senator, and 10 years before that in the House of Representatives. Though best known as the lead sponsor for the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, he remains as active as ever in shaping farm policy—and not without a few surprises.

On September 25, Harkin opened the two-day Industrial Farm Animal Production, the Environment and Public Health conference at his namesake Harkin Institute for Public Policy & Citizen Engagement at Drake University in Des Moines, Iowa. He admitted, “We made a lot of mistakes with ag policy in America.”

Since he was elected to the House in 1974, Harkin served on the Agriculture Committee in both chambers, and from 2001-2003 and 2007-2009, Harkin served as the Chair of the Senate Agriculture Committee, where he helped oversee the 2002 and 2008 farm bills.

“Like so many in our modern-day society,” Harkin said, “we thought the environment was free. And that was a big mistake.”

“There is a tremendous cost to be paid for our people, our communities, our health and our wellbeing, by this constant foot on the accelerator growth,” he continued. “We’ve gotten way off course in our country—and here in the state of Iowa—in how we produce meat in a humane, healthy, sustainable and environmentally-sound manner. We need a course correction.”

About 150 participants, farmers, academics and activists, traveled to Des Moines from as far west as California and as far east as New York ready to lead such a course correction. This conference brought optimists together to imagine a different future.

Co-sponsored by the Center for a Livable Future at Johns Hopkins University the theme of the conference and its panels, which ranged from nitrate pollution to the mitigation of health impacts were all connected to chapters of Industrial Farm Animal Production, The Environment, and Public Health, released in September. The book was edited by two of the conference’s speakers James Merchant, the founding dean of the University of Iowa College of Public Health and Robert Martin, the former director of the Food System Policy Program at the Johns Hopkins Center for a Livable Future.

For Martin, one of the goals of the conference was to get all these people together in the same room. “It’s easy to get discouraged working on some of these issues,” he said. “When you see so many concerned people coming together and trying to find common cause to work on these issues, it’s very encouraging.”

Attendees heard from journalists like Eric Schlosser, whose book Fast Food Nation: The Dark Side of the All-American Meal became the impetus for groundbreaking documentaries like Food, Inc., public officials like Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.), a current member of the Senate Agriculture Committee who has spearheaded legislation to protect family farmers from corporate consolidation, and academics like water quality expert Chris Jones, and scholar Loka Ashwood, a University of Kentucky sociologist and 2024 MacArthur “genius” Fellow.

“It’s kind of like [a] ‘Who’s Who’ in this room. I love looking at the name tags, because I can be like, ‘I’ve read your work, I’ve read your work,’ ” said Austin Frerick, who spoke on the harmful business practices of corporations like Cargill and Fairlife at the conference and is the author of Barons: Money, Power, and the Corruption of America’s Food Industry. “This is where the magic happens.”

Former Iowa Sen. Tom Harkin (center) listens to presenters at the Harkin Institute’s two-day conference on Industrial Farm Animal Production, the Environment and Public Health. (Nina Elkadi, Barn Raiser)

Harkin also spoke about the negative effect industrialized animal agriculture has on rural communities and schools. The vertical integration of concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs)—in which a corporation takes control of the links in the production chain such as feed production, slaughtering and packaging—has not only contributed to a decline in diversified crop and animal farming, Harkin said, but has also contributed to a degradation of “social infrastructure” in the loss of independent small businesses and family farmer, paired with a less-informed citizenry.

Harkin said:

“Environmental impacts of these colossal animal feeding operations, hogs, cattle and chickens are evident for all to see, whose eyes and minds have not been clouded by the siren song of the large conglomerate meat processors, Wall Street investors, certain farm organizations and the lack of incentives for true family farmers for a more sustainable, environmentally friendly, animal husbandry.”

According to new data compiled by Food & Water Watch, CAFO-raised animals in Iowa produce 25 times as much manure as its people. It leads the country in animal waste at 109 billion pounds produced annually.

“There operations are operating essentially as sewerless cities producing unprecedented amounts of waste,” Food & Water Watch Research Director Amanda Starbuck said at the conference. “We have about 1.7 billion animals living on factory farms producing about 941 billion pounds of manure each year. And just to put that in perspective, that is twice as much in human manure produced by the entire U.S. population.”

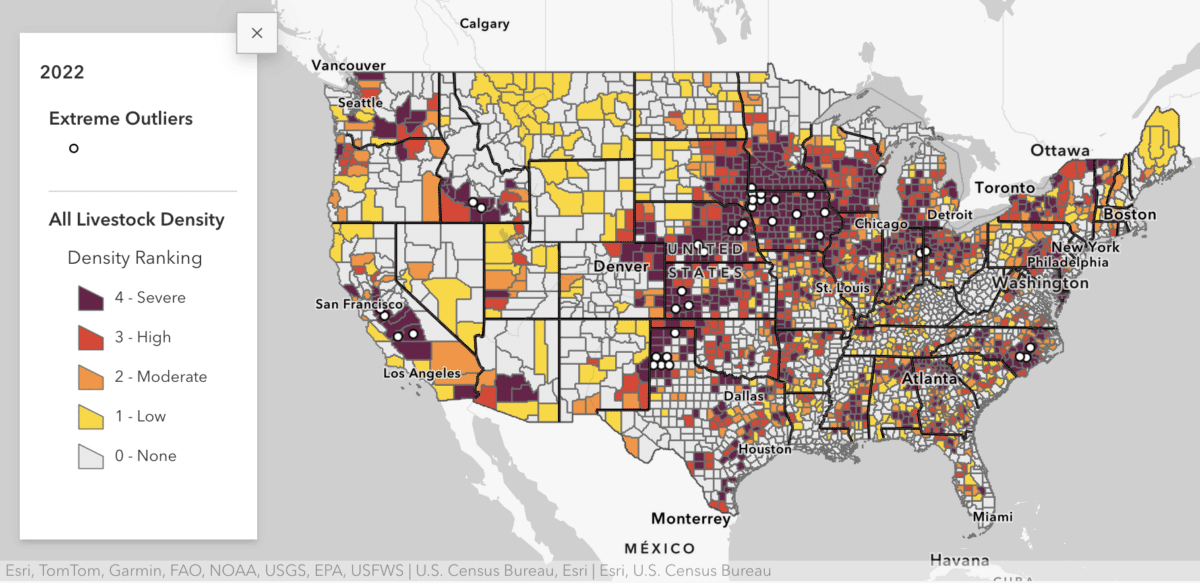

Food & Water Watch’s Factory Farm Nation 2024 report maps the density of factory farmed animals at the county level, covering 20 years of factory farm growth. (Food & Water Watch)

In a panel on the health effects of CAFOs, Merchant described multiple studies that connect living near CAFOs with asthma and other health problems. Iowa is the only state in the U.S. with rising cancer rates—and is the second in cancer incidence only to Kentucky. At the conference, Merchant tied these rising rates to CAFOs.

“CAFOs are harmful, undeniably, to the animals, the farmers, farm workers and rural communities,” he said, “We think this is playing a role in not only cardiovascular disease, but also lung cancer and possibly other cancers.”

And there is no end to the growth of this industry in sight.

Nebraska farmer Kevin Fulton grew up on a conventional family farm, but now farms animals on pasture, a system which stands in stark contrast to many of his neighbors. Fulton’s county of Sherman, Nebraska, has four factory farms that produce a total of approximately 74 million pounds of manure per year.

“I kind of live on an island back home. I’m a real outlier, so I don’t get a lot of support back where I live,” Fulton said. “So, I come here, and I get really energized.”

Rancher Ron Mardesen also spoke on a panel about regenerative agriculture.

“I’m lucky enough that in the 80s, I drew a line in the sand. I said I would not put my pig in a concrete box. I would not put my chickens in a steel cage. I expected my cattle to roam on the pastures,” he said. “This is kind of like the Gettysburg where we’re at, things are going to have to change. Things are going to change.”

The reference to Gettysburg became a common refrain at the conference after attorney James Larew, the registered agent for the Driftless Water Defenders, identified it as the turning point for the Civil War.

“There were massive armies on either side, and it happened that five roads came together in a little village. I think we have the equivalent of Gettysburg, if not in northeast Iowa, somewhere close, because the forces are too large, they can’t avoid each other, and they’re going to have to find ways, under the law, to allow us to exist in a healthy and fruitful way,” he said. “I am of the view that a very profound change in how we think about the environment is going to happen in Iowa, because the ingredients are here.”