You might have read about the ”carbon tax” that Denmark will, as the first country in the world*, apply to the agriculture sector. While I certainly agree with taxing carbon dioxide emissions, the proposed Danish tax is counterproductive and is not a carbon tax at al.

Let’s start with the basics. In June 2024 the Government of Denmark, the Danish Agriculture and Food Council, the Danish Society for Nature Conservation, the Confederation of Danish Industry, a trade union and the Danish Local Government Association agreed to a number of measures for the agriculture sector.

A climate tax on agriculture of 300 DKK (EUR 40) per ton of carbon dioxide equivalent emissions (CO2e) in 2030, increasing to 750 DKK (EUR 100) by 2035 will be introduced. A basic tax break of 60% will be applied to farms according to rules not yet defined (I believe it is supposed to be a kind of incentive for farmers to accept certain measures, but I am not sure about that interpretation. After the tax break, the effective cost will be 120 DKK (EUR 16) per ton of CO2e in 2030, and 300 DKK (EUR 40) in 2035, still considerably lower than the societal costs of greenhouse gas emissions.

Revenues from the tax will be channelled back to the sector and reinvested into green initiatives, climate technology, and production transformation, targeting the agricultural sectors facing the most difficulty transition. Approximately 40 billion DKK (EUR 5.4 billion) will be allocated to The Green Landscape Fund. This money will support the creation of 250,000 hectares of new forests, the restoration of 140,000 hectares of peatlands, further land conversion, and strategic land purchases focused on nitrogen reduction. To encourage farmers to give up their peatlands, a CO2e tax on emissions from carbon-rich peatlands of 40 DKK (5.36 EUR) per ton will be introduced starting in 2028. This tax will only apply to farmers who do not wish to participate in the peatland restoration. There will also be a tax on emission caused by liming agricultural soils.

Denmark is the country with the second highest share of agriculture land in the world, 59% after the 62% of Bangladesh, so regardless how you farm it seems like a good idea to diversify the landscape. I can’t judge if the measure for re-wetting and afforestation are reasonable and have not studied the details in the proposal.

It is no carbon tax- it is a livestock tax

When it comes to the so called carbon tax on farming it is important to note, that apart from the small levy on peatlands and the tax on emissions caused by liming, there will be no tax on the of carbon dioxide from fossil fuels or chemical fertilizers, which are the main sources of carbon dioxide emission, or any other source of carbon dioxide emissions (plastics, steel, concrete etc.). The emissions that are subject to taxation is methane and nitrous oxide emissions from livestock. Not only are the carbon dioxide emissions exempt but also the considerable nitrous oxide emissions from the use of nitrogen fertilizers. I have no specific data for Denmark, but on the global level nitrogen fertilizers is the single largest source of greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture if one include the emissions from the whole chain.

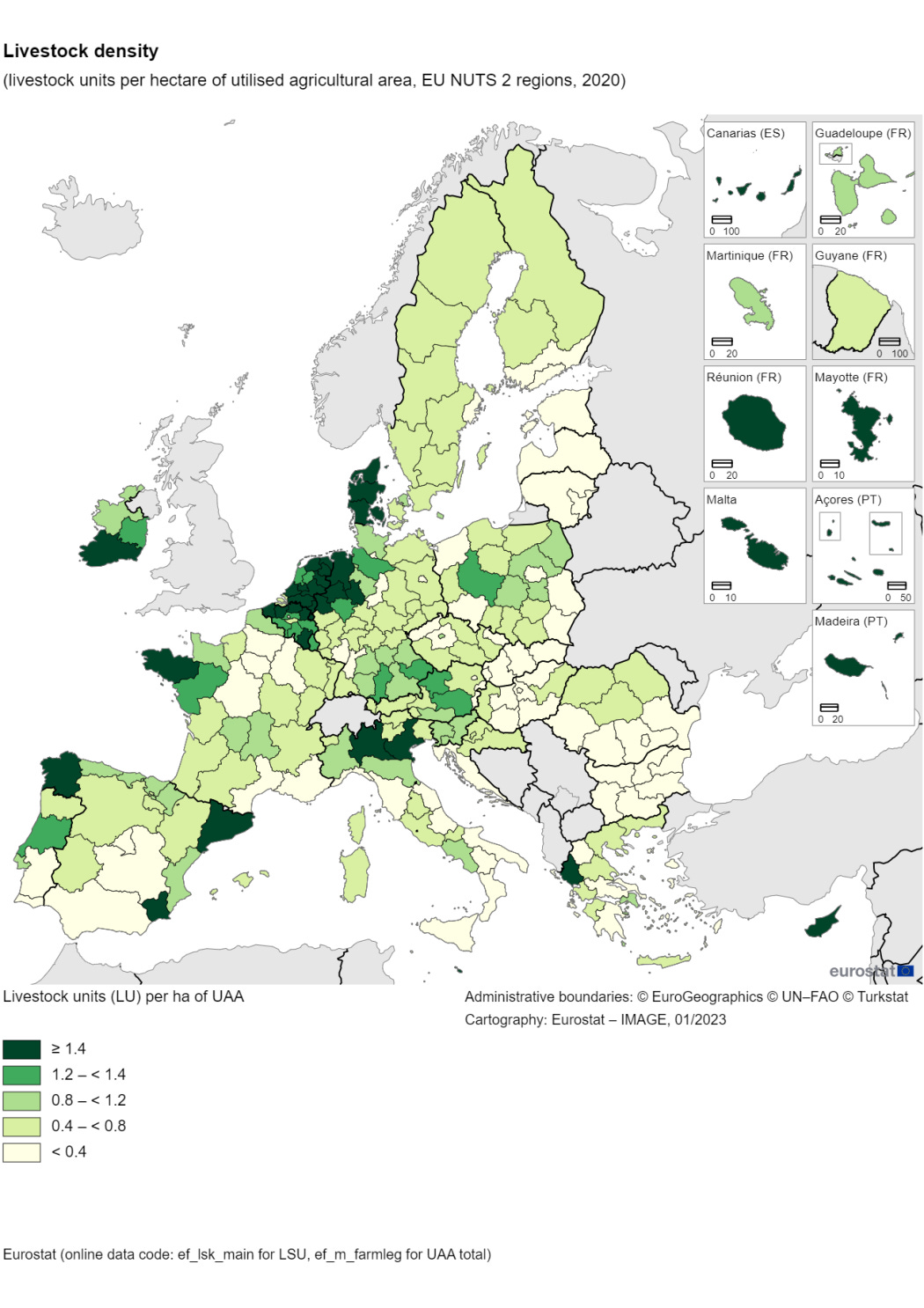

Clearly, Denmark has an oversized and very intensively managed livestock sector, 1.6 livestock units per hectare and it imports a lot of feed so there are good reasons to reduce the numbers (the livestock sector has actually decreased considerably lately).

But most of the animals in Denmark are pigs, the pork production is more than 10 times bigger than the beef production. The dairy sector is also considerable. Pigs will be comparatively lightly taxed in the proposed system.** Ruminants, such as cattle, sheep and goats, have much higher emission than monogastric animals as a result of how methane − erroneously − is calculated. In addition, the same metrics also assign much higher emissions per unit produced from extensive management of animals which means that the tax will affect grass-fed livestock very hard and indoor chicken and pigs very little.

In line with this industrial thinking, farmers will get a support for the use of methane-reducing feed additives to cattle. The symbiosis between the animal and methane producing microbes (archaea) is a defining character of ruminants and the idea that we should supress this process is just another step in industrialization of livestock keeping and essentially in violation of fundamental animal welfare principles. In addition, it only works for livestock that has controlled feeding, i.e. animals in feed lot style operation and not for grazing animals. There are no provisions to account for the considerable carbon sequestration that can take place in pastures and arable grasslands (leys), which could off-set some or all of the emissions from grazing and grass-fed livestock (as opposed to those in feed lot systems).*** Finally, as the climate effect of methane is considerably exaggerated by the metrics used, it will also have a marginal effect on the climate.

Notably, the emissions will be based on standardized values and not on measurements on the farms. The latter would be totally impossible due to costs and methodical reasons (e.g. it is very intrusive to apply methane measurements to cattle). But there are many indications that the standard values for emissions, especially for nitrous oxide, can differ very much from standard emission factors, e.g. from grazing ruminants. This is also a problem for the compensations that farmers will get for various measures that are supposed to reduce emissions.

What next?

The agreement is not yet put into legislation approved by the Parliament and there is quite some opposition. The governmental Climate Council claims that the agreement is far too optimistic about the cost for the large scale reforestation and that bigger incentives –or outright expropriation is needed. It is also worth noting that the agreement is not only about climate but also about reducing nitrogen emissions. And here there are trade-offs. For the reduction of nitrogen emissions to water, the best soils in intensive production areas should be taken out of production, while for carbon sequestration purposes marginal soils can be planted. The cost for the government will be much lower if farmers are compensated for taking marginal land out of production instead of prime arable land.

Paul Holmbeck, long time president of the organic association in Denmark and current board member of IFOAM writes on Linkedin that the agreement “set in stone the current industrial production, targeting research and investment to more of the same, making climate fees ineffectual, investing in dubious technical fixes and sending the bill to the public rather than to polluters. The agreement includes almost no efforts for organic farming, that in Denmark has proven to be the single most effective tool for reducing two of the most problematic issues for clean water and biodiversity (on land & in the sea) in Denmark: pesticides and Nitrogen pollution from fertilizers.”

That there are still many struggles and conflicts to resolve was made clear in the latest re-shuffling of the Danish government, where a minister and an separate department was tasked with the implementation of the agreement.

We need rapid action yes – but the right action

Climate change is real and to a large extent caused by the emission of greenhouse gases (see more below). And there are good reasons to take prompt action against those emissions now. The obvious target that is quite straight forward is the emissions caused by the combustion of fossil fuels. In agriculture, nitrogen fertilizers is also an obvious target.

To try to regulate the biogenic emissions of methane and nitrous oxide is quite a different story. Natural eco systems also emit methane and nitrous oxide but in the greenhouse gas accounting methods for agriculture all emissions of methane and nitrous oxide is considered anthropogenic, which makes any zero emission target for agriculture impossible to reach.

In addition, there are huge uncertainties in the cycles for methane and nitrous oxide and how they are affected not only by direct emissions but by a host of other processes. For instance, the functions of the atmospheric methane “sink” (it is not really a sink but a process by which methane is broken down) is to a large extent unexplored. There are also huge uncertainties about how efficient different methods to reduce emissions are. Even for generally recommended measure such as tree planting, soil carbon sequestration or re-wetting the actual climate effect is uncertain in many cases. Recent research in Sweden show that under certain conditions, emissions can even increase with re-wetting. Emissions from liming of agriculture soils have shown to be very varied and in many cases total emissions are actually lower when soil is limed.

“There are so many things we don’t understand about ecosystems. They’re incredibly complex.”

says Christian Frølund Damgaard, professor at the Department of Ecoscience at Aarhus university,in an interview in Phys.org. This was about a recent study of biodiversity in grasslands in Denmark, but the same goes for the dynamics of greenhouse gases in ecosystems.

It is true that emissions of greenhouse gases are main drivers of climate change. But life on the planet is also an important agent for shaping the climate on earth in many different ways apart from direct emissions, including, but not limited to, driving the water cycle and reflecting or absorbing sunlight (albedo and particles). Human manipulations of the planet other than emissions and direct sequestration of greenhouse gases also influence natural processes to a very large extent. The tremendous increase of reactive nitrogen in the biosphere (mainly as a result of chemical fertilizers), overfishing, reduction of biodiversity, land use changes, the paving of land, drainage, dams are all having climate effects over and above the direct emissions. To base climate policy primarily on greenhouse gas budgets is far too simplistic and it is even worse to aggregate the various greenhouse gases into one dubious metric such as carbon dioxide equivalent. In the end, the inclusion of biogenic greenhouse gases tend to draw the attention away from the fossil fuels, to the benefit of the fossil fuel industry, which is just happy if cows get all the attention.

The failure of the Danish climate tax on agriculture is a result of a siloed science and policy with no consideration of the realities of agro-ecosystems. Landscape management need to be multi-faceted and not directed towards just one objective, be it climate regulation, maximum harvest, profit, bio-diversity or tourism. Things are made worse when general policy targets are applied indiscriminately, regardless of the local conditions. We would have more to gain from moving from the landscape level upwards rather than the top down approach now prevalent in both climate and biodiversity policy. But more on that another time.

* New Zealand has also a proposal in the pipe, which at the moment is put on hold.

** A lot of the Danish pork is exported to China and as China also is a major importer of feed. It makes perhaps little difference on a global level if Denmark reduces the number of pigs if China increases its production correspondingly, or if some other country picks up the slack.

*** There is considerable controversy about this, I discuss it in depth in this article.