An economy not dependent on endless growth

This is the second part of a scenario for how a city comes together to address the multiple economic, social and environmental crises facing our world. The first part of the scenario is here. It covers how the city creates basic frameworks of life. How it gains control of its own finances and local economy through creating a public bank. How it ensures everyone has shelter through creation of social and community housing. How clean energy is supplied while energy use is reduced through creation of community energy cooperatives.

In this part, the scenario will cover how the city develops the basics of an ecological economy not dependent on endless economic growth. It develops local and bioregional production of basic necessities including food. It sets up circular material flows that eliminate wastes. It builds worker-owned cooperatives with a broad range of social and environmental goals. As a touchstone of its efforts, the city prioritizes people and communities underserved by the standard economy, who are most in need of alternatives.

Worker Cooperatives: Productive work for all

Even when times had been good, many people still fell between the cracks, unable to find adequate work or any work at all. When the economic bubbles building up over many years burst, plunging the economy into depression conditions, many more were tossed out on the street. It was crucial for the city to help create new employment options. The intensifying climate crisis, manifesting in many natural disasters including storms and wildfires, as well as the general stress on lands, waters, wildlife and forests, underscored that those options had to reduce the pressure on ecological systems.

These criteria pointed to worker-owned cooperatives that aim for more than the bottom line, but also to sustain the maximum employment in the most ecologically sustainable manner. So the city public bank funds worker coops, financing worker buyouts of existing businesses large and small, and creating new economic institutions. In this way, local small businesses ranging from restaurants and shops to service and trades companies have come under ownership of their workers. Some larger enterprises have also gone coop.

Growing supply chain difficulties underscore how unreliable the global economy has become. Goods are increasingly back ordered or unavailable. The city looks to re-localize and re-regionalize production to the greatest degree possible. It aims to produce manufactured goods through organizations modeled on the Mondragon Cooperatives of Spain, one of the world’s largest industrial cooperatives. The community assembly that developed the local agenda (see the first part) commissioned a city economic planning group to identify goods that could be produced in the bioregion. Replacing the most commonly used goods with local and bioregional production was the priority. The group came up with a list that included clothing, construction materials, bicycles, and basic household goods such as furniture and appliances.

The city bank has funded a number of cooperatively-owned enterprises. Networks of distributed and decentralized shops use open access designs to make goods, employing flexible manufacturing techniques, computer numerical control machines and 3D printers. These are capable of producing basic items as well as sophisticated equipment such as tools, heat pumps and other energy saving equipment. Flexible manufacturing allows production in small lots, eliminating the need for mass production, with an emphasis on quality and durability. Together these eliminate the drive to planned obsolescence. So people are willing to accept higher costs for goods that last.

Because many areas are engaging in such initiatives, the city reaches out to other communities to create flexible production networks, with the aim to supply vital goods as close to home as possible. This reduces energy and pollution from long-distance shipping. The city fosters an understanding that buying goods made in the area keeps money recirculating, promoting local and bioregional prosperity. It also promotes the idea that local and bioregional production in worker coops fosters social justice in a way goods imported from afar might not. So, as with durability, people are willing to spend a few more dollars for goods made in the area. (I am indebted to Paddy Le Flufy for introducing me to some of these concepts. His book, Building Tomorrow: Averting Environmental Crisis With a New Economic System, is an invaluable guide to new economic concepts.)

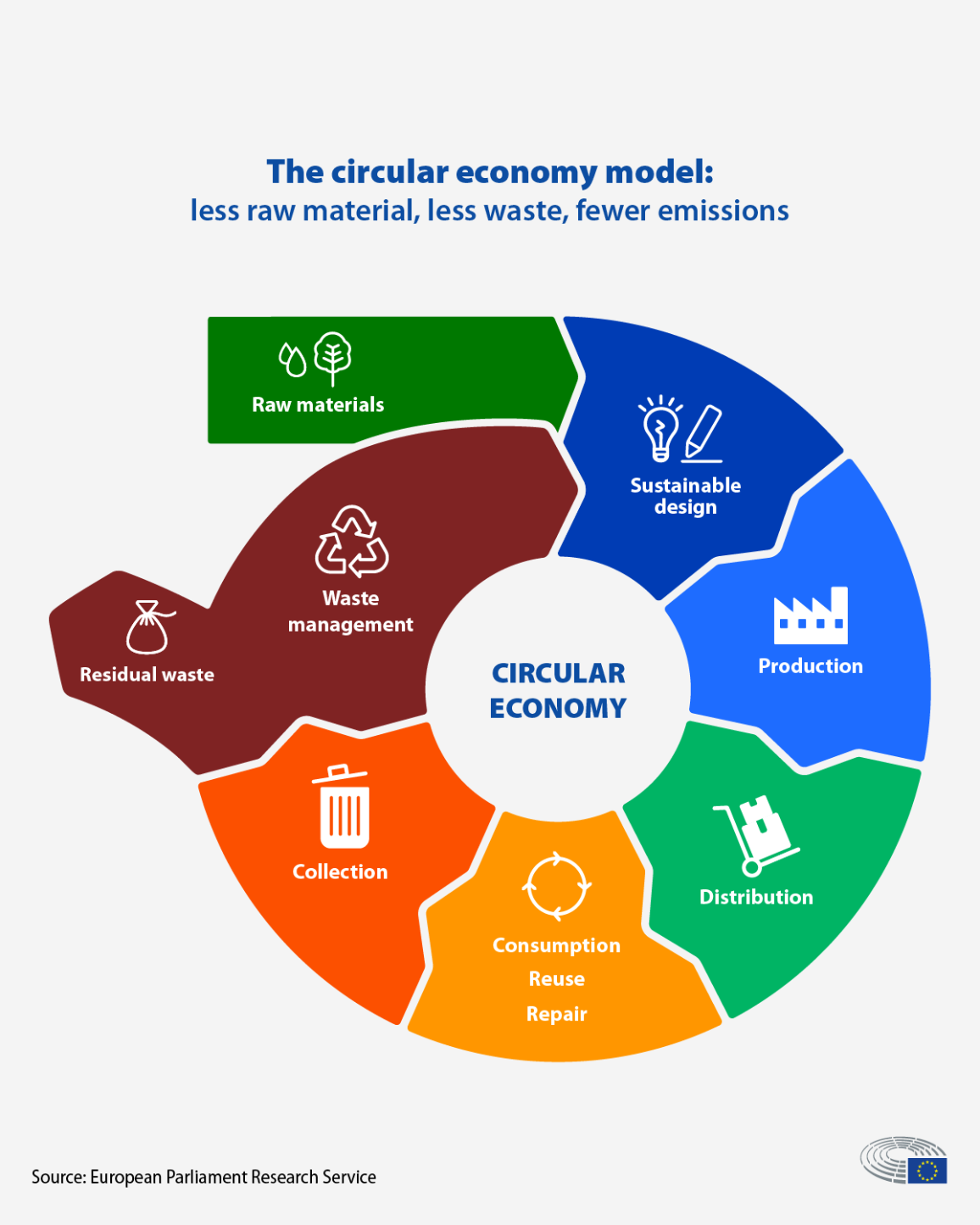

A circular economy that minimizes material use and recirculates wastes to produce new goods is fundamental to an ecological economy. Credit: European Parliament

Sustainable Materials: Closing the loops

In building a new local and bioregional economic base, the city emphasizes reducing wastes to zero in both consumption and production systems. This circular economy strategy is vital to reduce climate pollution and other impacts on the natural environment. Building on existing recycling efforts, city economic planners identify opportunities to transform wastes into valuable products. Having a city bank making financing decisions according to a broad range of environmental and social criteria makes this more possible. On a strictly bottom-line basis it is often still more profitable to use virgin materials. With a priority on creating closed loop economics, the city bank capitalizes worker coops and other businesses that instead base production on recycled materials. The clothing industry, for example, relies heavily on recycled textiles. As noted above, focus on long-term durability is vital to reduce waste.

In developing new local and bioregional economic institutions, the city aims to create industrial ecosystems where possible. These co-locate businesses where one’s waste, such as wood fragments from furniture production, becomes feedstock for another, for instance making construction materials from those fragments. The municipal waste treatment system is leveraged to produce materials such as composts and biochar.

But producing new goods is not the only goal. Reducing demands for goods is also emphasized under an emerging strategy known as sustainable materials management. This ramifies back up the supply chain to reduce mining, logging and pollution. In making funding decisions, the city bank gives priority to enterprises that reduce material consumption. The city has revitalized the tradition of the repair shop, and also hosts repair cafes where people can bring broken items to be fixed by experts. Enterprises that refurbish items such as mattresses, appliances and computers have been created. It has supported right-to-repair legislation at state and federal levels. The city has also created libraries of things that let people borrow items such as tools, really, anything that people only occasionally use. Rental businesses are also encouraged.

(To learn more about these concepts, check out a report on sustainable material use to which I contributed, done by the Center for Sustainable Infrastructure, From Waste Management to Clean Materials: A 2040 Blueprint for PNW Leadership.)

Local Food Systems: Ensuring food security

An increasingly turbulent climate causing crop failures around the world underscores the need to build local systems to provide food security, especially to economically stressed populations. While it is impractical to completely replace long-distance food transport, creating networks that supply food closer to home is a crucial priority.

The city builds efforts to link local and bioregional food producers with its residents. These include creating on-line systems through which people can order food and producers can ship food, community supported agriculture that makes direct connections between producers and consumers, and farmers markets. An urban extension service helps people start home gardens. The network of community gardens has been expanded so residents without yard space can grow their own food. Social and community housing typically includes areas for food production including rooftop gardens.

The city bank funds urban agriculture farms and enterprises to process food, as well as sheds for local and bioregional producers to ship and store food in the city. Rooftop greenhouses powered with solar and geothermal energy allow year-round, local production of fruits and vegetables formerly imported from long distances. The city also builds networks to reduce food waste, channeling items that restaurants and groceries might discard to food banks. Recognizing the emerging insecurities around food supplies, the city has created an emergency granary and food storage in case of natural disasters and other crises.

In line with the priority on serving economically stressed populations, the city sets up food coops and purchasing clubs in food desert areas, and targeted extension and community garden efforts to these areas.

Conclusion: Only a start

This scenario for how a city can build the future in place, addressing the converging crises in our world by local action, is only a broad brush vision. It is by no means exhaustive of all that can be done locally or bioregionally. (And of course we should continue to work for change at all levels.) Each of the areas covered in these two parts has models that are already working, to be examined in future posts. I invite readers to call out models, help refine this vision, and point out places where it can be enhanced, or where there are gaps in my understanding. As well, it is only a partial picture. Other key items such as water, transportation and health care are also crucial.

My hope here is to begin stirring the imagination for what we might do, to create a picture of key areas where we can act in place to build a better world beginning in our own communities. The problems afflicting our world sometimes seem intractable. We have the greatest leverage to make change in the places where we live. Let’s use it.