There are plenty of books and websites telling you how forest gardens should work. I am more interested in how they do (and sometimes don’t) work, and in the people who are working in and with them.

In my book, Forest Gardening in Practice you can meet some of the pioneers who have been planting, tending and harvesting their sites, often away from the spotlight of media and research, for years and sometimes decades. Each of these case studies is a tale of discovery and self-discovery, of successes and setbacks, sometimes planned and often unsuspected.

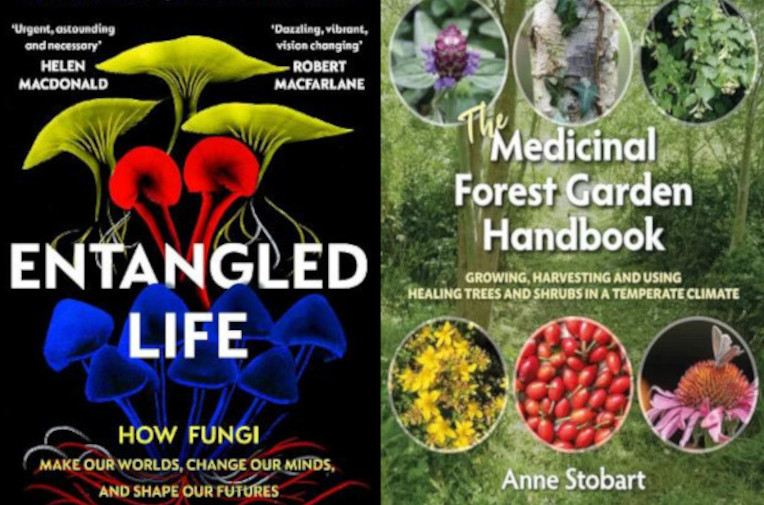

Here I review 2 excellent books that I’ve read recently:

Entangled Life, by Merlin Sheldrake

Not long ago fungi were regarded as weird plants, somehow lumped into a family that stood out awkwardly from the photosynthesising rest of the kingdom. Our knowledge of what fungi are, do and signify has accelerated at the rate of hyphal growth in recent decades, yet it is clear that we are still only at the beginning of our understanding of these truly remarkable life forms. At this point in time, Merlin Sheldrake’s summary of what we know is as good as any you could ask for. He speaks from a position of great understanding, having (sometimes literally) immersed himself in the subject of his enquiry for much of his life.

There seems to be nothing that’s beyond Fungi. They colonise and connect plants, trade substances with them and redistribute nutrients over large distances underground. Their network of mycelial tubes branch, split and reconnect in response to the environment around them. Fungi are the chief agents of decomposing life. They can make animals do their bidding by producing sex hormones and brain stimulating substances. People are now inciting fungi to grow buildings, furniture and packaging, clean up pollution, heal people’s bodies and alter their minds, thereby helping fungi move around the world. “Are we domesticating these fungi or have they in fact domesticated us?” is one of Sheldrake’s provocative questions.

On a fundamental level, fungi challenge us to re-examine some of our core concepts about the living world. They defy and dissolve notions of individuality and classification. Symbiosis is built into their way of being. Often it is a moot point whether they are benefiting or exploiting their symbiotic partners – in fact any such assessments seem to say more about the perspective of the observer than about the fungus itself. As one researcher puts it, “collaboration is always an alloy of competition and co-operation”.

Lichens, one of the unassuming stars of the show, amalgamate not only photosynthesising bacteria and fungi but a whole host of other bacteria and viruses, forming an entire ecology within themselves. Their presence in the world has dissolved rocks since life first emerged on land. They also convey to us that identity does not equal individuality, a lesson that applies to human as well as fungal existence. No body, no life form is an island – everyone is an ecosystem. And part of one.

I found this a hugely enjoyable, engaging and thought provoking read. Whether Sheldrake is hunting truffles in Italy, sniffing samples of rainforest soil, peering through the lens of a microscope or scrumping apples in Newton’s Cambridge garden, he takes you right there with him into the experience. The book is also full of “WOW” moments that will make you put the pages down and spend some time readjusting the way you see the world. If you want a mushroom grower’s guide, try Paul Stamets who, unsurprisingly, is one of Sheldrake’s mentors. To change your sense of how the world works, there is no better book than this.

The Medicinal Forest Garden Handbook, by Ann Stobart

A great many forest gardens have sprung up over the last couple of decades. People have developed the concept in all kinds of directions, exploring their potential for production, wellbeing, learning and ecological restoration. This book showcases one of the most promising developments. Given the great diversity present in forest gardens and the fact that practically every plant has a medicinal value, the medicinal forest garden idea seems a natural fit that should appeal to home gardeners, medicinal herbalists and professional growers alike.

Ann Stobart is well placed to explore this exciting concept, having developed her own site and business – Holt Wood Herbs in Devon – in this way since 2004, together with her partner. This book is the distillation of her extensive research and practice over the years.

The book comes in two parts – a general introduction to the subjects followed by a detailed presentation of 40 medicinal shrubs and trees. The first section covers a wide range of topics. As the book amalgamates two disciplines that are both vast in their own right, it starts off by briefly introducing the principles of both forest gardening and herbal medicine. This is followed by a deeper look at relevant subjects, from designing and planting a forest garden, harvesting plants and using them for their beneficial effects, sourcing plants and making your own. The physical and mental health benefits derived from gentle activity in the open air, in direct contact with plants (what Robert Hart called “purposeful meditative gardening”) are also explored. Another intriguing concept is overlaying the conditions in the ecology around us with that inside our own bodies, leading to suggested guilds for specific health issues or body systems.

The specific advice in section 1 is largely based on Ann’s experience at Holt Wood Herbs, where she and her partner converted a conifer plantation into a forest garden. Most people will work in different settings to that, but the general principles covered in the book are universal. Brief case studies mainly from the UK and US help to broaden the reader’s horizon by showing some of the diversity of forest garden settings. The book also discusses the relative merits of wild harvesting, forest gardening, agroforestry and farm woodlands in producing medicinal plants.

The detailed directory of plants restricts itself to 40 trees and shrubs suitable for a wide range of sites and addressing many conditions. While it is not intended to replace an in-depth medicinal herbal directory, it is a great introduction to the subject for beginners. For experienced herbalists, the book opens up the possibility to develop their own living pharmacy.

Ann wisely decides to leave out too much of the finer detail on forest gardening or herbal medicine which is already amply covered by other authors. Nevertheless her deep knowledge comes through in the writing. At the same time the book is immensely practical. As a serial forest gardener and amateur herbalist, I look forward to using this book as a frequent source of reference.

[First published in Permaculture Magazine.]