I worked for almost two decades with smallholders in developing countries, in particular East Africa. The projects were market-oriented with the aim of increasing income, mostly through export commodities such as coffee, cotton, cocoa and sesame seeds (you can read a book about the largest project EPOPA, here). When I started the work I had some knowledge about the situation for smallholders and I read quite a lot to better understand their economic and agronomic situation. It was apparent that they didn’t always, or even mostly, followed the advice of well-intentioned agricultural advisors. Those often complained that farmers were ignorant, lazy or simply not good farmers. Their economic behaviour could also appear to be somewhat irrational from an entrepreneurial perspective.

The world of development assistance, which was what I worked with, is strongly coloured by a view that smallholders are backward and irrational. The debate is mostly between those that want to modernize them into commercial commodity farmers and those that want them to retire and simply move to cities. Ironically, on the system level, the result is more or less the same. If farmers modernize, they will start a process whereby the more successful will take over the land from others and fewer people will work the land; the same process that has transformed agriculture in the developed countries (i.e. the countries that are responsible for most loss of biodiversity and global warming).

Meanwhile, smallholder farming has shown to be surprisingly persistent and a rough estimate is that around one fourth of the global population live in smallholding households. Even in a country such as China, that has undergone rapid transformation, there are still some 200-300 million small holder households, according to some estimates.

It didn’t take long before I realized that the social component of being a smallholder was more important to understand their situation than various economic theories, and that the way they farmed often was quite rational if one considered their total situation and not looked at farming as an isolated commercial enterprise. In the cases farmers didn’t manage their farm properly, unless they were sick or too old, it was often because they prioritized other things, or were forced to do other things, e.g. take a job or engage in small trade or prostitution to get cash.

A recent research article by Flora Hajdu and colleagues from the Swedish University of Agricultural Science, published in Journal of Rural Studies, emphasizes the need to take the social relations and conditions into account when discussing smallholders. They call it “rendering the smallholder social”. Based on 36 studies in 19 countries across Africa, Latin America and Asia they formulate five social themes that are essential for understanding smallholders’ behaviour and development paths.

A. The social values of land and landscape. The value attached to the land can not be reduced to its price or productive potential. Through inter-generational obligations the land stretches back in time to ancestors and forward to descendants and inheritors. There is also a sense of belonging to the land and the land is also a kind of safety net when other livelihoods fail.

B. The authors identify three aspects of the the social values of farming. 1) While waged work was much appreciated, many said it felt good just to work for yourself and be your own boss. Especially gardening is easy to combine with other livelihood activities and household chores. 2) Home-grown food was sometimes viewed as tasting better, to be healthier and safer. In some cases, traditional crops or varieties were not available in the market so growing yourself was the only way to get them (something that it is easy to relate to also for many gardeners in developed countries. 3) By involving the younger generation the social values are transmitted also in the future.

C. Caring in the countryside. Rural areas and home villages play an important role for care work and reproductive labour. The authors make the point that “the smallholder household is as much a unit of social reproduction, as it is a unit of economic production… Reproductive labour, and especially care for children and the sick or elderly, is intimately – functionally and relationally – linked to ‘productive’ household members who are engaged in non-farm and off-farm work, often far from home.” There is thus often a mutual dependence between the homeland-household and the urban labourer, and not just one stream of remittances from the urban to the rural, sometimes even over continents.

D. The village and the countryside as a buffer in times of crisis. People do not only leave rural areas for better opportunities, they also come back in times of crisis, personal or social. A forty-year-old metal worker in Thailand explained: “[I keep my land but] just for a rainy day. If I fail in this job, then [at least] I still have my rice land to work”.

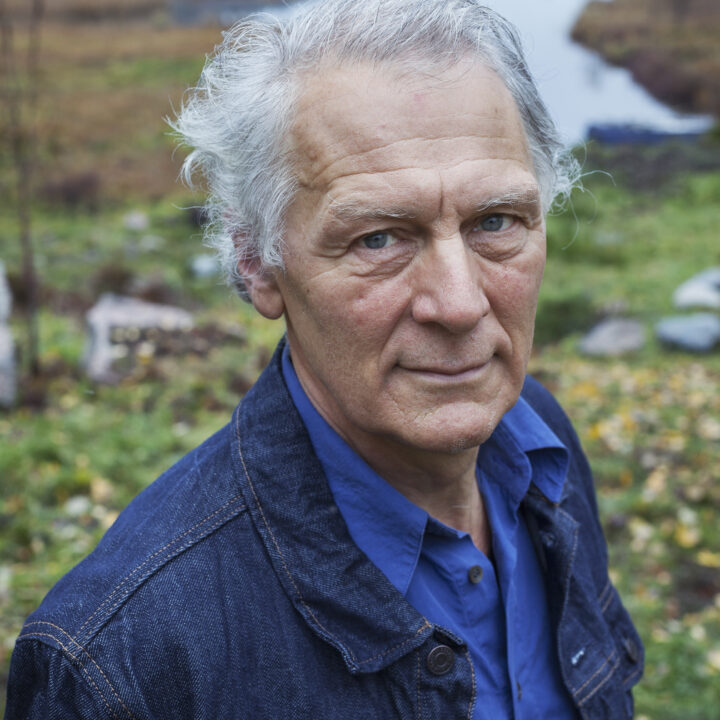

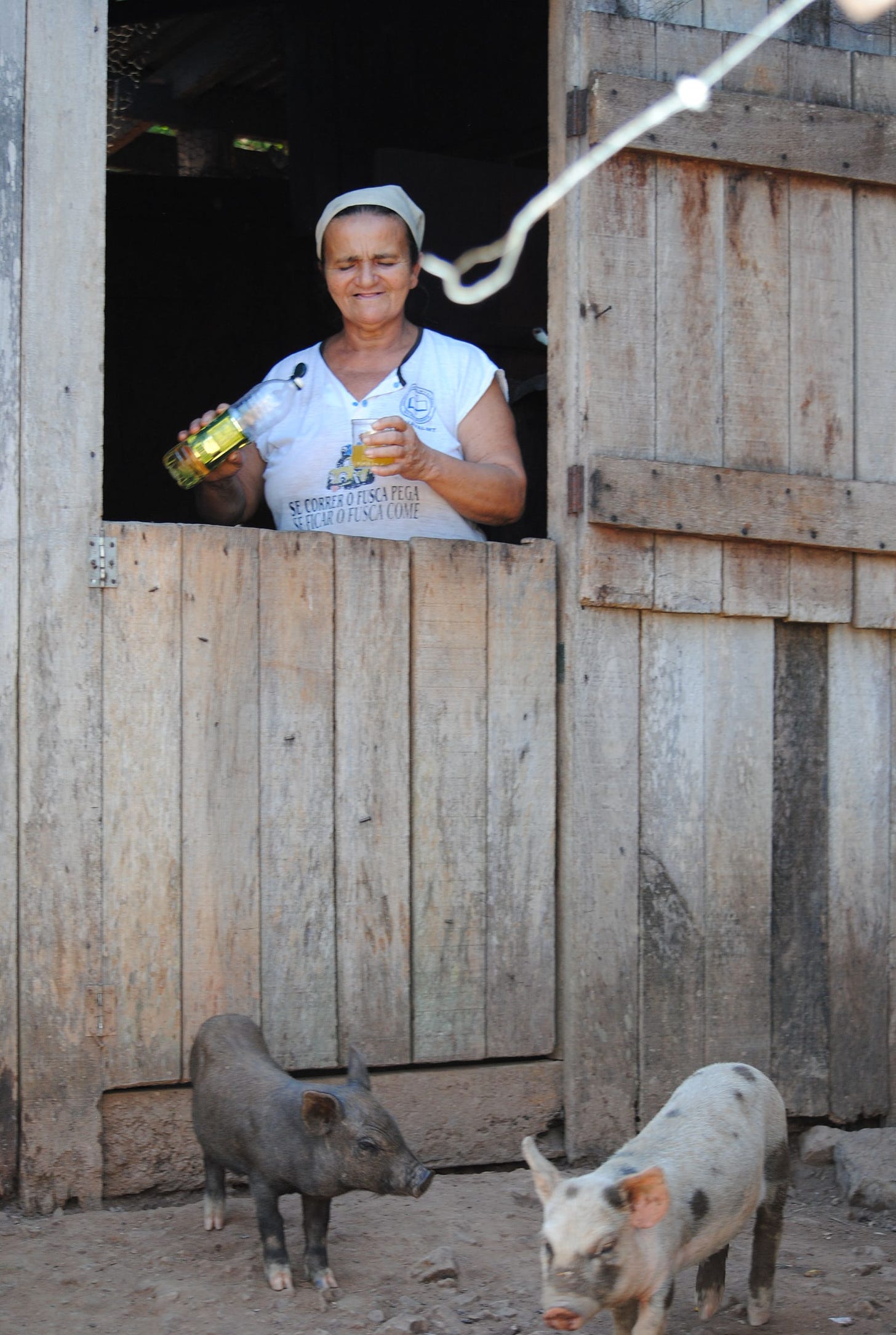

The smallholder Maria Viera in Nova Esperanca, Matto Grosso, photo: Ann-Helen Meyer von Bremen

E. It is not only middle class back-to-the-landers like myself that romanticize rural living and rural life, also economically poor smallholders can appreciate the clean air, the joy of work, the good environment and the social relationships. Living well, living frugally in the rural is the fifth social theme in the article.

In 2012, Ann-Helen and I visited Maria and Louis Viera, farmers in the Amazon, and noted how much they valued their life, despite extreme initial hardship:

”The two first years, while we cleared the land, we survived on rat, palm heart, the flour from the babassu palm and other wild plants,” Maria Viera says when she receives us in her home in the small settlement Nova Esperança, where the road ends and the vast Amazon takes over. She is just 57 years but looks older, and that is no wonder when we hear her story. Nine children she has carried, of which six are still alive. She has diabetes, a wound with emerging sepsis and just three teeth in her mouth. But she is full of life, just like her husband Luis. He can’t sit still for a second; he talks incessantly and is excited that we have come all the way from Sweden to visit them and their farm.

Maria and Luis think their life is good now and their farm is an example of how you can have a decent life with small means and a small ecological footprint. Solar panels produce enough electricity for a few lamps, a TV and a radio, not more. They have their own well water from the mountain, led by gravity into the house; the sewage water goes into the fish pond. Even though there is a gas stove, most of the cooking is done on the wood stove – they get firewood from their own forest. Today there is a road. Even if that is not passable in the rainy season, it is a great improvement compared to the mule path that was there when they came.

We are offered a simple but good and nutritious meal of beans, rice, meat and lettuce – all from the farm. It is a typical meal, according to Maria. For breakfast they drink home-grown coffee and bread made from the wheat that they buy. https://gardenearth.substack.com/p/agroforestry-in-amazon

Notably, the themes are not equally significant in all situations. For instance, among migratory farmers practicing shifting cultivation over long time scales or pastoralist, land has often not the same importance. Returning to the village is also not always welcome. “Villages – as social collectivities – can act as safety nets and places of welcome and solace at times of need; but they can also judge harshly” in the words of the researchers. In Nigeria, women returning to the village were assumed to be lazy and a failure and if they were pregnant they were said to have ‘run home to hide’.

The researchers conclude that the persistence of smallholder farming is based on these social relations and that “Seeing the smallholder household not as a unit of economic activity, a collectivity of human capitals, or as a source of labour, but first and foremost as social and relational allows for a different perspective to emerge on why smallholders have endured through development time.” Meanwhile, they also emphasize that smallholders are in most cases “enmeshed in the modern world, underpinning capitalism through their rural reproductive work.”

Of course, there is almost no possibility for anyone to avoid the net of global capitalism, whether you like it or not. And smallholders are both voluntary and involuntary caught in it as well. But I would say that many smallholders try to balance the wish and need to get cash income and the wish to maintain a certain level of autonomy, for the household and for the community. The themes of the research cited above can be contrasted to developments in society which undermine the social web of small holders.

One such process is the privatization of land. In many (most?) traditional societies, land can’t be privately owned but is held in common by the villages and allocated to households according to some rules. If you leave the community you will lose the right to the land. The drive to convert communal land to privately owned land, mostly in the name of “development”, change all this and is, therefore, a long term threat to the smallholder social web.

The conversion of small holders to farm entrepreneurs is another path by which smallholders are made totally dependent on the capitalist economy rather than being opportunistically involved. In my book Global Eating Disorder I describe a job I did for the World Bank in Samoa some 15 years ago like this:

“I was part of a World Bank team assisting the government in the development of a program to increase the competitiveness of the agriculture sector, to be financed by credit that would be repaid in a distant future. My role was to look into the opportunities for commercial organic production. Commercializing production would mean that farmers sell their produce in ‘the market’ to earn more money. But it also would mean farmers using more inputs – that they generally need to buy – including credit, fertilizers, irrigation and advisory and business planning services. In this way they could increase productivity and their incomes. That is the idea at least.

Part of the price to be paid for this is increased risk. But there is more: when traditional farming systems are brought into the market economy, the change is more than just technical or economic. The whole village social context is disrupted, reducing the role of the village and the extended family. When visiting farms, I realized that many farm families seemed to be happy with their way of life. When I asked directly what they would like for their business, they came up with nothing related to increased production, higher income and the like. There were few incentives for individuals to invest in commercial production as the benefits will be shared by so many. The very rocky soils make mechanization virtually impossible, so it is unlikely that Samoans can ever be competitive in commercially cultivating any annual crops. One of the few larger scale farmers I visited had bought soil and put a thick layer of topsoil on his land to cover the stones.

In personal terms the job on Samoa was very rewarding. Professionally, as a consultant it contributed to my growing uneasiness of being asked to recruit farmers into the global market economy, and leading them and their country into debt. At the end of the day, I found it hard to wholeheartedly recommend commercialization as the best solution for Samoan farmers and communities, not even commercial organic production. I suspect that the World Bank will no longer want my services, and even less so after reading this book.

Even if the situations differ, there are many of these themes that also apply to “smallholders” in so called developed countries. I will discuss this in the next article.