Sometimes I hear something about the modern world which stops me dead in my tracks. Here’s one tidbit that did it for me recently: it takes 10 calories of fossil fuels to produce 1 calorie of food for human consumption.

There’s different versions of this statistic because it’s hard to know where to draw the line – do you just count the inputs on the farm? Do you count the the meat factory that processes the food? What about the machines that make the machines that process the food? It’s like pulling a piece of string. But on average, in the industrialised world, it is about 10 fossil fuel calories for producing 1 calorie of food, processing it, transporting it, retailing it, and cooking it.

In the US alone, it takes about 35,000 fossil fuel calories – equivalent to about a gallon of crude oil – to feed a person for a day (with the average person needing 2,600 food calories daily).

Breaking it down into cups of crude oil, with 16 cups in a gallon, farming operations use 2.5 cups of oil, food processing uses 3 cups, packaging and transportation combined account for 1.67 cups, while retailing and restaurants together consume about 4.33 cups, with household activities requiring 4.25 cups.

Breakdown of the 35,000 fossil fuel calorie inputs

Farm operations account for 15.9% of the total energy inputs – so that’s about 5,565 fossil fuel calories to feed a person for a day.

We have a slight advantage here in Ireland, with cattle grazed out in the fields most of the year. But we still rely on maize imported from the US, soy from Brazil, nitrogen fertiliser from Norway, phosphorus fertiliser from Morocco, and diesel from OPEC. So we’re in or around the same ballpark.

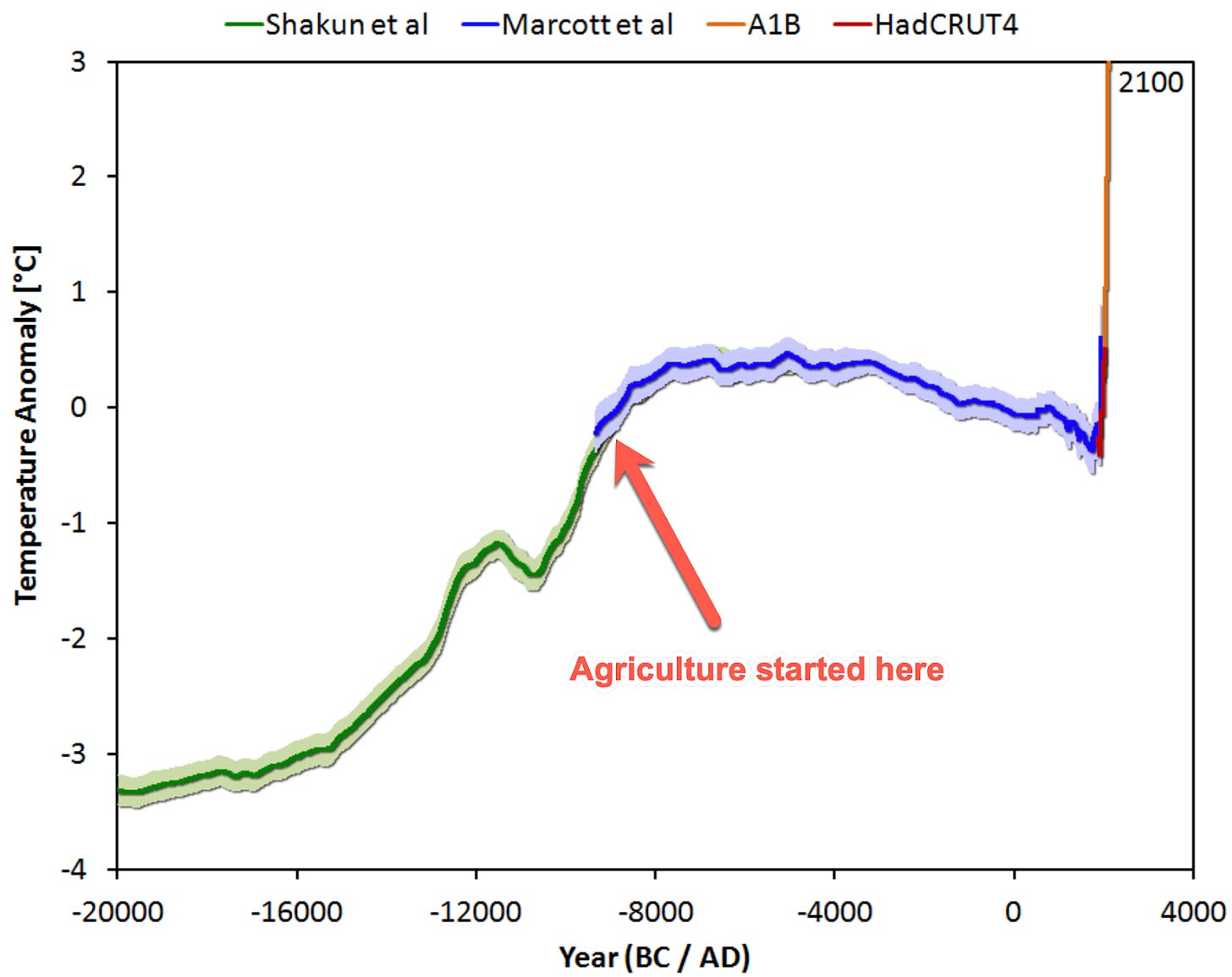

When hunter-gatherers were hunting and gathering, they were a lot more efficient than we are now. For every calorie expended, they acquired about 69 calories in food. When the climate system stabilised 12,000 years ago and civilisations around the world established agriculture, this dropped significantly – with all the extra work needed for cultivation of crops and whatnot – but was still net energy positive.

However, with the advent of fossil fuels in the 1900s and increased intensification of agriculture, greater use of pesticides, herbicides and fertilisers, this flipped on its head and the food system became an energy sink rather than an energy source.

I mentioned above the establishment of agriculture 12,000 years ago after the climate stabilised. Well, burning 100 million years worth of ancient sunlight in less than 200 years has set the climate adrift again. If emissions stopped tomorrow, 40% of the excess emissions would still be in the atmosphere in 100 years. 20% would still be in the atmosphere in a 1,000 years. Climate change will continue to amplify for decades, centuries, millennia – even if we stopped emissions tomorrow – as the system slowly tries to find a new equilibrium. Agriculture has relied on stability, but the stability of the holocene is leaving us.

Agriculture was established as temperatures stabilised

Which brings me to the focus of this week’s blog – the “sustainability” buzzword. The term has never really fit – last year saw record levels of CO2 emissions, breaking the previous record set in 2022. To sustain any of the present system is to accelerate faster towards the brick wall. Every week brings a different version of the headline in the Farmers Journal headline from last week “Ireland is becoming a global leader in sustainable agriculture”. The word “sustainability” is thrown around like confetti, but if you asked different people what it means, you’d get a different answer each time.

But it is actually very easy to define. Sustainable agriculture is when all energy inputs into the production of food, from farm to mouth, are renewable. Currently, virtually none are.

So sustainable agriculture has 2 problems. It’s not sustainable because of the complete and utter reliance on non-renewable energy inputs, while agriculture relies on a stable climate system, which is now leaving us.

There is nowhere in the industrialised world where food is produced sustainably. The only place where that happens is the non-industrialised world where the main 2 energy inputs are forms of renewable energy – human and animal muscle power.

You would think that many people would be working on this extraordinarily important problem, and building towards a food production system that runs entirely on renewable energy. But that doesn’t appear to be the case. Any piece of policy you look at is a tweak around the edges of a system completely reliant on an endless supply of oil and gas.

It reminds me of the old joke: a guy goes to a doctor and the doctor says “I’m afraid I’ve got bad news. It’s terminal and there’s no cure. There isn’t even a race for a cure”.

Until we recognize the urgent need for a systemic overhaul, not just minor adjustments, we’ll remain locked in a race without a finish line.