In 2007, the Marcellus Shale Play was opened for production in Pennsylvania. The fracking of the shale unlocked massive fossil fuel reserves previously considered inaccessible. But it also unleashed an especially expensive and wasteful extraction process that involved flushing hundreds of millions of tons of highly toxic chemicals a mile deep into the ground and into the water table. And it brought up natural gas contaminated with unprecedented levels of radioactivity.

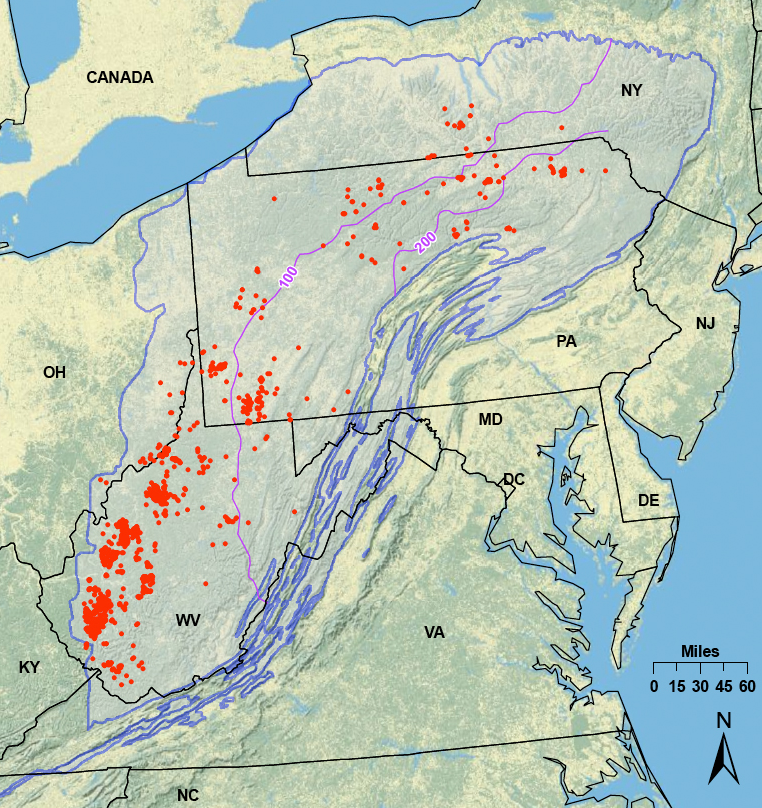

2009 geological map of the Marcellus shale play showing the extent of its development as the fracking boom was getting started. Red dots indicate the placement of individual wells (Energy Information Administration).

An underacknowledged actor in this race to secure the energy stores of the Marcellus is the government. Hydraulic fracturing, like the Internet, was a technology developed by the federal government before getting picked up by industry actors. Major politicians across the spectrum threw their political weight behind fracking. Not least among these was President Barack Obama, who called fracking a “bridge fuel” that could “power our economy with less of the carbon pollution that causes climate change.” The federal government also made a massive investment in Liquefied Natural Gas infrastructure to transport fracked gas over long distances.

More consequential and insidious was the government’s policy of systematically exempting oil and gas development from the regulatory framework governing hazardous substances. Recall, for example, the infamous “Halliburton loophole,” passed under Vice President Dick Cheney in 2005. Or, less frequently mentioned but still more shocking, the erosion of the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know-Act, legislation that the federal government passed in the wake of the Bhopal disaster to prevent a similar disaster from occurring on American soil.

However, the question I pose here is not what enabled this government-sanctioned poisoning of the land. Instead, I ask how we could ignore the extent of this involvement when it is so glaringly obvious. The answer, I argue, lies largely in the economic dogma that we have been conditioned to accept.

The way popular understandings of economics shape our ability to accurately perceive the role of government in the fracking boom is an extremely complex and nuanced problem. The small facet I attempt to tackle here is the role of our belief in the free market. I examine how this belief blinds us to the symbiotic collaboration between government and corporations that was necessary to secure the Marcellus Shale for production.

A Paradox of Perception

When I began interviewing residents affected by fracking in southwestern Pennsylvania for my dissertation at the University of Pennsylvania in 2020, I was quickly struck by what I will term here a “paradox of perception.” Some residents had taken a militant stance against the fossil-fuel developments in their backyards. Consequently, they had developed a sophisticated understanding of how government and industry colluded to enable fracking development in their communities. Yet these same people often believed that fossil-fuel companies were the only ones who could produce positive economic outcomes in their communities.

![]()

Frack pad in Potter County in northcentral Pennsylvania, one of the epicenters of fracking in the state (Ted Auch, FracTracker Alliance).

Consider Roger, who spent five years attempting to reverse the improper renewal of a well permit on his property. At the local level, Roger was acutely aware of the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection’s favoritism toward the fossil-fuel industry. But this did not change his belief that the fracking industry generally functioned under free-market conditions. To him, a free market operates by default to pick out the best possible outcome. So if natural gas is dominant in the current market, then it must automatically be the best form of energy.

In my research, I labeled this disconnect “splitting.” Splitting refers to our collective blindness to how governments and corporations operate symbiotically to secure a source of energy that the state deems crucial for its continued existence.

So where does this blindness originate? The truth is people very rarely update their core beliefs based on new observations. Once capitalism implanted in our collective consciousness the idea that the free market automatically picks out the most socially desirable outcomes, it takes a lot to dislodge that belief.

This status quo is then reinforced for emotional reasons. Once people living in extractive economies accept the narrative of fossil-fuel companies as bullish entities who alone possess the brashness and vision to pull their region out of its economic slump, a kind of learned helplessness sets in. They become nervous about scrutinizing the narrative too closely. Sure, companies may be illegally dumping in our local streams, but if they were to leave, that would be worse.

And I believe the biggest fear is actually internal. How would our sense of security be affected if we acknowledged these fault lines in our narrative of economic growth?

Holes in a Bridge to Nowhere

Traveling on a bridge to nowhere (Jake Cook, Flickr)

In the spring of 2019, just a few months before the first leg of my fieldwork in southwestern Pennsylvania, I remember trying out a new shortcut on my bike from Penn to where I used to live in South Philadelphia. The shortcut led over a bridge spanning over a now defunct oil refinery just three miles from my old home. What I didn’t anticipate was that the bridge was so worn it had actually developed holes. I remember a powerful sensation of vertigo seizing me as I peered through the gaps in the bridge at what I believed was the industrial wasteland below.

The other thing I didn’t know was that the refinery was still active and would explode the day after I left for my fieldwork. The explosion sent a container the size of a school bus toppling into the Schuylkill River and came within a hair’s breadth of killing thousands of people from hydrogen fluoride exposure.

This put me in an embarrassing position. I had just embarked upon fieldwork to understand how so many rural citizens could tolerate extractive industries in their backyards. Now it turned out I was just like them.

But this experience also gave me valuable insight into what might be motivating my subjects’ selective blindness. The impulse I felt to look away from the holes in that bridge came to symbolize for me how I could live so long next to an oil refinery without any awareness of the risks it posed to me and my community. Ironically, I think it felt safer to me to simply assume that it wasn’t active. Allowing for the possibility that it was still active raised too many issues I had no idea how to resolve.

Resisting the Siren Call of the Markets

Humans don’t always react to threats by burying their heads in the sand. The key is to try and understand why, in the case of threats posed by industrial development, we mostly do. Anthropologists David Wengrow and the late David Graeber would probably argue that this is because we have lost our capacity for “actuarial intelligence.” This is the capacity to understand “what society might look like if [we] did things differently.”

When the direction of the world seems completely out of our hands, it makes sense to ignore the problems we notice. If we can’t do anything about the holes in the bridge, we would rather forget about them so we don’t have to think about falling.

I believe this perceived lack of agency does more to explain our unwillingness to let go of perpetual growth and free-market fantasies than just about anything else. It is tempting to believe in the free market precisely because we experience our economic system as unpredictable and fickle. Revisiting our bridge metaphor, our deepest fear when questioning the wisdom of neoliberal economics may not be that we could fall off the bridge. It may be that we’ll realize the bridge was never there to begin with.

Tuning out the signal of ecological destruction and tuning into the noise of stock market fluctuations is a self-soothing technique. But we all know what happens when this kind of denial of facts causes us to ignore real dangers. Take the false claim that served as an ideological launchpad for our latest foray into fossil fuels: that the fracking industry could lead to economic growth without sacrificing the environment. This is the central claim that the CASSE position refutes. But focusing on this tradeoff overshadowed another truth: Locals never benefited economically from the GDP growth engendered by the industry.

Still, we want to refrain from judging people trying to find footing on the deck boards of a nonexistent bridge. Clinging to a false narrative is a fundamentally human reaction in the absence of a better choice. Our real problem does not lie in the flaws in our current belief system, but in our failure to articulate an alternative. It’s time to construct a sturdier bridge to coax us off the fanciful one. And before we have a chance of building that better bridge, we have to deconstruct the old one to get material for a narrative that can actually hold us all up.

How to Deconstruct the Deck Boards of the Growth Myth

According to Merchant, historical depictions of nature as female and sacred used to act as restraints against the unrestricted exploitation of natural reserves (Engraving attributed to Theodor de Bry or Matthaeus Merian, Wikimedia).

Coming up with a better story than the one that led us to the brink of global environmental disaster has to be the task of many people from all walks of life, not just a select few. It has got to include both Harris and Trump supporters, people from the Global South and the Global North. The rich, but especially the poor. It has got to involve the kind of coordination and coalition-building that we have stopped feeling capable of. But the alternative is to continue allowing people to tell our story who do not have our best interests at heart.

I am committed to being a part of creating this story. This is how I envision my authorial contribution to the Herald: as helping to chip away at the deck boards of the old bridge, one by one, in preparation for the new one.

Oilfield canal in the Louisiana Bayou showing the disruption of natural ecosystems by fossil fuel development (Louisiana Sea Grant Collective, Flickr)

There is only so much I can achieve with an average of 1,500 words per article. But I can do my part to strengthen our collective muscle for thinking through how we know what we know. My aim will be to interpret the news cycle from the angle of steady-state principles and to point out the common blind spots in our environmental and economic news coverage.

As part of this process, I hope to hold under the microscope different elements of the myth of limitless economic growth. I am thinking for example of the belief that GDP growth can be converted into environmental conservation or that the pursuit of economic self-interest will always result in maximizing group benefit.

I will be drawing from the work of the many excellent thinkers who came before me to make my case. Some of these works will be contributions to the CASSE canon. I am thinking, for example, of Herman Daly’s historical account of how we came to consider “land” a superfluous input in the economic production function.

I will also be introducing additional influences from my own reading. These will include among others Carolyn Merchant, whose ecofeminist book The Death of Nature shows how Enlightenment thinkers sanctioned the exploitation of nature. Or of the urban sociologist Harvey Molotch, whose theory of the “growth machine” gives us a framework for understanding how land speculators managed to convince the rest of us of the intrinsic value of for-profit land development.

With their help, I hope to interrogate where our ideas about the environment and our economy came from, how we can shake them off, and how we can learn to replace them with something better.