This is the third article in a series discussing the “curse of the straight line”, which is shorthand for the polycrisis of modernity and the industrial civilization. In the previous article, I discussed to what extent markets could save the industrial civilization. They can’t. Markets and capitalism are essential features of and drivers of the industrial civilization and they can’t be re-configured to counter their own imperatives. Or as Murray Bookchin phrased it “to quarrel with its very metabolism”.

In this article, I turn to science and technology. They are even more fundamental building blocks of modernity and industrial civilization than markets.

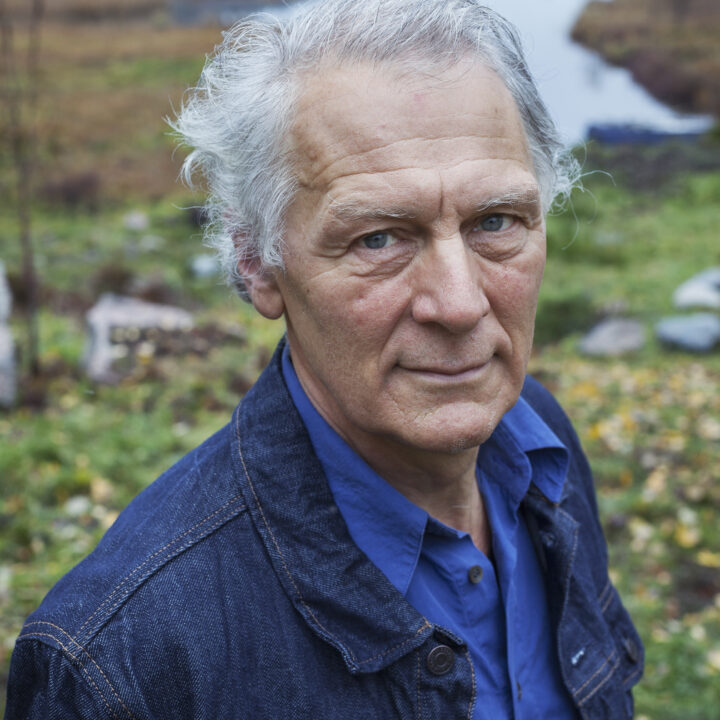

My father, Frithiof Rundgren, published an essay 1972 where he wrote that: “The essence of science as a form of life is to be faithful to the truth gained through centuries of struggle, and to never stop believing that this truth will once make all people free”* I am sure my father meant it when he wrote it. I know that later in his life he would not have written the same, as it expresses an exaggerated and naïve view of science and something that often is called “scientism”.

The quote from my father reflects the environment in which I grew up. The time, 1960s, was a time of optimism, progress and expansion, moon landing, nuclear power and the rise of computers. My father was a language professor at the University of Uppsala. My mother was also well educated and very interested in natural science and provided her three children with chemistry kits, rocket propellants and electronic equipment to take apart and reconstruct. Most of my friends also had parents who were researchers, teachers and alike. My heroes were the great natural scientists like Albert Einstein and Marie Skłodowska Curie or explorers like Roald Amundsen.

But gradually, I lost faith in that science could save us. Many of the emerging problems, e.g. environmental pollution and nuclear waste were a result of the application of science. Other flaws in our societies, inequality, war and abject poverty were not for science to fix. The only “scientific” approach to understanding and transforming society was Marx’s and Engels’ theories of historical materialism. The practical application of that science was not encouraging, to say the least.

The scientific method, as mostly defined, is not wrong per se, it has many useful applications. But it certainly has a tendency towards myopia, seeing what you are searching for and has difficulties with complex systems and emergent properties. This quote of Albert Szent-Gyorgyi, a Hungarian biochemist and Nobel Laureate expresses this well:

“After twenty years’ work, I was led to conclude that to understand life we have to descend to the electronic level and to the world of wave mechanics. But electrons are just electrons and have no life at all. Evidently on the way I lost life; it had run out between my fingers.” **

Scientists are obviously not unbiased neither in what they want to research nor in the conclusions they draw from their research. In addition, those that provide funds for research are biased which means that some things, e.g. biotechnology, get immense funding while others, e.g. agro-ecology, get very little. Which science that finally is published in respected academic journals is also subject to biases. For example, the highly ranked journal Nature selects articles which are of interest for a “broad readership” and the selection is made by editors. Nature even makes a point of that it has no scientific editorial board and that they therefore are “unbiased by scientific prejudices”. The peer review of scientific articles also suffer from biases of the reviewers. The fact that there are multi-level biases in science doesn’t, of course, mean that science is a fraud. It just means that you need to have that in mind when you interpret the results. All other perspectives on reality, including mine, clearly have biases. Even a respected body as the IPCC has biases. For example, none of their scenarios include a total abolishment of the use of fossil fuels and none of the scenarios include a situation with no growth or de-growth. Those are clearly politically or value driven choices of scenarios. Global warming is also a good example of the limitations of science to get us out of predicaments. While the IPCC can make scenarios and predictions and in that way advise policy, how societies handle climate change is about values, norms, culture and power relationships.

For sure, science has enhanced our perspectives and knowledge. Those who follow my writing know that I make ample references to research findings. Meanwhile, science doesn’t tell us how to live and how to die. While science itself perhaps shouldn’t be blamed for it, the idea that science is the only path for our understanding of the world, suppresses other ways we experience reality. If science is the Truth, what is then beauty, love, emotions, moral and values? My point is certainly not that science as such is bad, but that we should not put it too high on the pedestal and in that process disregard other ways to understand what it is to be human and how we should live.

Even if science isn’t a cure-all and it has some limitations, there are, of course, useful things coming out of the busy laboratories, computers and brains at research institutions. Meanwhile, it is not very clear to what extent many technologies are a result of science or rather of the kind of non-scientific innovation or tinkering that has been common in most human endeavours. Farming is perhaps one of the most striking examples where most crops, machinery and production techniques have not been developed by science. Having said that, there is a cross-fertilization between science and more entrepreneurial technological development stretching a long way back. Improvements in tool-making, e.g. microscopes, binoculars and scales, have been essential for scientific progress, which in turn made new technologies possible. It is intriguing to contemplate where science would be today without pencils and books.

Some claim that new technologies will save us and that instead of “collapse” we will just have a seamless transition of the current civilization to some version of eco-modernist future. Common components of those visions are photovoltaics or nuclear/fusion energy instead of fossil fuels, microbial fermentation instead of farming and biotechnology in all kinds of applications giving us eternal life or miracle crops. As there are many versions of this, here is not the place to expand on the limitations or drawbacks of each and every such proposition. The problem with them is mostly not that they are not possible − even fusion may sooner or later become technologically possible – the problem is mostly that they don’t deliver what they promise (genetic engineering of crops and animals), that they are far too resource demanding (nuclear power and microbial protein) or that there are considerable limitations or disadvantages (all) as part of the deal. In addition, under capitalism it is the prospects of profit that will determine which technology that is actually applied and not whether it is “good” or “bad” for humanity at large, not to speak about the rest of the living.

Another version is transhumanism which foresees a “human” without any or most limitations imposed by the environment or our biology. In its most extreme form humanity has migrated to the virtual world and everyone is thus immortal. Common for both eco-modernism and transhumanism is the desire to break the ecological context which, so far, defines humanity. Microbial proteins produced in steel tanks are not food with any meaning, context or beauty, and they seek to make us independent from farming, pastoralism, hunting, fishing, foraging or any other way we have fed ourselves. They are not food at all, actually, at most they are a fraction of the nutrients the human body needs. Transhumanism just takes this a bit longer by including also our bodies in the project. Both miss the main point that this ecological context is essential in making us human and that if you take that away there is no homo sapiens left to care for. As much as we are our bodies, we are also our ecological context.

The renewed interest in space travel and colonization of other celestial bodies is perhaps somewhere in between transhumanism and eco-modernism and business as usual. Simple math makes it apparent that colonization is a project of limited interest for humanity at large. The whole colonization dream is a strange combination of an insight that we have screwed up our stay on planet Earth and the idea that the same features that made us do that will by some magic be useful in space. The more modest ambition that space travel can be useful for expanding our knowledge (it can!) or extract some very valuable minerals (sure, but they have to be incredibly valuable to motivate the costs and it is hard to believe they can) is hardly a solution to the polycrisis, but rather an expression of the kind of hubris and boyish expansionism that is the cause of it.

While the embracement of eco-modernism and transhumanism has a scientific aura, they express a faith in that human ingenuity can abolish all boundaries. This faith is obviously not scientifically grounded but is an expression of values, emotions and desires. Apart from all other shortcomings, they thus fail also on the principles of science they supposedly adhere to.

In the next article I will discuss some external factors that will determine or at least set limits for how our destiny will unravel.

* In Swedish original, “Så kan det väsentliga i vetenskapen som livsform endast vara trohet mot det som under seklers kamp vunnits av sanning och en aldrig sviktande tro, att denna sanning en gång skall göra alla människor fria.” in Vetenskapen som livsform, Frithiof Rundgren 1972

** Unfortunately, I have not managed to find the reference to the original quote, but it can be found in several serious publications – which is not a guarantee for authenticity…But as the journalists say: ”never check a good story” (a quote in turn attributed to Mark Twain, but I haven’t found the ur-source to that either).