This is the fourteenth of 18 installments in the Metastatic Modernity video series (see launch announcement), putting the meta-crisis in perspective as a cancerous disease afflicting humanity and the greater community of life on Earth. We have arrived at the episode whose concept inspired the name of the series. Though no metaphor can perfectly capture a complex reality, by comparing modernity to metastatic cancer I hope to provide a useful framework that counters the usual modernity-boosting narratives we swim within.

As is the custom for the series, I provide a stand-alone companion piece in written form (not a transcript) so that the key ideas may be absorbed by a different channel. The write-up that follows is arranged according to “chapters” in the video, navigable via links in the YouTube description field.

Introduction

This is the usual short naming of the series, of myself, and the topic of this episode (modernity as metastatic cancer) as part of our effort to put modernity into context.

Organ–Species Analog

The first step in recognizing the merit of a modernity–cancer comparison is to appreciate the parallels between an organism and an ecological community of life.

An organism, such as the human body, is composed of a number of organs—each playing a distinct role within the whole, and each interdependent on the health of the others. An organism doesn’t work because of the organs themselves, but because of the relationships between the organs—pulling together toward some common goal. We never encounter a lone intestine roaming the street trying to make ends meet (get it?), without the rest of the body supporting its existence.

Like an organ within an organism, a species is a member of a whole community of life. Every species forms relationships with other species in an inter-dependent web of life. A squirrel cannot survive without a surrounding ecology supporting its existence. The squirrel, in turn and in part, helps plant trees and spread nutrients around.

Both organisms and communities of life arise from a process of co-evolution—its organs or species inextricably inter-related throughout the entire process. The stomach evolves in lock-step with the kidneys and lungs, never out of relationship. The same is true of a species in an ecological context: every step in its development happens in close contact with developments in all the interacting species—whether direct or not.

Now getting to the central analogy, cancer afflicts a single organ within the organism, eventually taking down its host. The fatal result is to the detriment of the cancer as well, which cannot survive without the health and resource support of its host. Similarly, modernity afflicts one species (Homo sapiens) within the community of life, resulting in the whole community of life suffering. The result appears to be the initiation of a sixth mass extinction, as touched on in Episode 7. Just as in the cancer case, modernity’s “success” is its own undoing—cutting the necessary and supportive ecological foundation out from under it.

I present below five relevant parallels between cancer and modernity.

1. Anomalous, Unchecked Growth

Cancer arises from a random mutation, producing a behavior utterly uncharacteristic of the tissue during its long life before cancer struck. A defining characteristic is unchecked growth. The function of the afflicted organ suffers from the presence of this swelling growth, translating to an increasingly dysfunctional organism as a whole.

Modernity arose as a mode that was unusual and very new in the long history of our species, producing a set of unprecedented behaviors. Notably, the entire process has been characterized by growth of the human enterprise and footprint. Not only does this produce a fair bit of strife within the human “tissue,” but eventually impairs the whole community of life.

2. At-Risk Tissues

Cancer could, in principle, afflict any organ. While it is certainly possible to have two independent cancer instances start in two different organs, the usual case involves just one. Some organs do prove to be more susceptible than others—like lungs, colons, breasts, or prostates. We don’t blame the organ for the cancer, which is something that happens to it, not caused by it, per se. If someone gets pancreatic cancer, we don’t hate the pancreas for it, which prior to the cancer was just going about its business as a functioning member within its organism.

The Planet of the Apes movie franchise might argue that modernity could have afflicted a species other than humans. I’m not going to stand behind such a statement, but it is at least the case that modernity afflicted only one species on the planet. It is not hard to make the case that humans were more susceptible to the onset of modernity than other species. I trace it to our brains, whose flexibility and superficiality allowed an untethered departure from our ecological context. Just as we don’t blame the victim (organ) in the case of cancer, we need not blame humans for coming down with modernity. We might sympathize with ourselves and send get-well-soon cards.

3. Evolutionary Dead-End

Cancer has no path to a “win.” It cannot pass on its mutant genetics to future generations, because it is a one-off aberration that has no reproductive mechanism. It is not part of evolution: not part of the co-evolved inter-relationships in the community of life. It has no path to sustaining itself. Other diseases are different, in that they co-evolved with other life using a reproductive strategy that involves infecting a host (not usually to the host’s death). Cancer is essentially not a form of life, but of death: death of both the host and of itself.

Modernity is also a mode that lacks a proven adaptive strategy for its long-term success. Rather than participating in reciprocal relationships with the community of life, it rips through said community with callous disregard. If modernity keeps getting its way, it executes a sixth mass extinction, which kills its host and thus itself—very similar to how cancer operates. By not being crafted and honed by an evolutionary process to adhere to sustainable design, modernity has not purchased a ticket to a long-term future. We can only hope that it does itself in before ending the line for both humans and a wide swath of the community of life.

In short, neither cancer nor modernity are participants in biological evolution. They are not a form of life—which is important to recognize. They both lack the necessary two-way support within their contexts.

4. Hungry Zombies

A cancerous tumor acts like a hungry zombie. It grabs an ever-increasing portion of resources (blood flow and sustenance) as it expands. The host is increasingly starved of critical resources.

Most of us are aware of the stupendous appetite of modernity in terms of energy and materials. Because modernity involves runaway growth, the flow of resources shoots up in hockey-stick fashion. These resources don’t come from nowhere, and their waste stays with us (no nucleons are created or destroyed). Like the organism being starved by a cancer-afflicted organ, the community of life is deprived of the habitat and environmental context in which it evolved. More for modernity means less for life.

5. Metastatic Phase

Eventually, cancerous cells spread to the rest of the body, starting new tumors wherever they land. Initially, only the organ where the cancer began is impacted, followed by a general resource drain felt by the whole organism. But in this final stage, many other organs are directly impacted and incapacitated by the presence of the growth.

In the modernity case, humans bore the affliction for some time before damage to the broader community of life began to accumulate. By now, the ills of modernity inhabit virtually every corner of the planet, affecting virtually every species in some way. It has fully metastasized, and is severely impacting ecological health. The current situation has every appearance of having started a sixth mass extinction.

Win–Lose Situation

What’s good for the cancer is bad for the host. Your doctor probably will not prioritize the cancer’s prosperity. As pointed out before, cancer is not a viable form of life: it has no evolutionary path, no vetting or reciprocal relationships, and no role in a healthy body.

Likewise, what’s good for modernity is bad for the community of life—of which humans are a part. See, for instance, the tangled interconnections between the Likes of modernity and resultant Dislikes in Episode 10. Given this, why be the kind of doctor (PhD, even) who prioritizes the prosperity of modernity? How does this comport with a “do no harm” motto? Or is the motto strictly meant for human supremacists?

Like cancer, modernity is not a viable form of living on this planet, demonstrating overwhelmingly negative impacts on the community of life, which itself is vital to human well-being. In the long run, modernity requires the very thing it destroys: a healthy ecology—which has no room for the modernity tumor. That’s called a fundamental incompatibility.

The Human Tumor

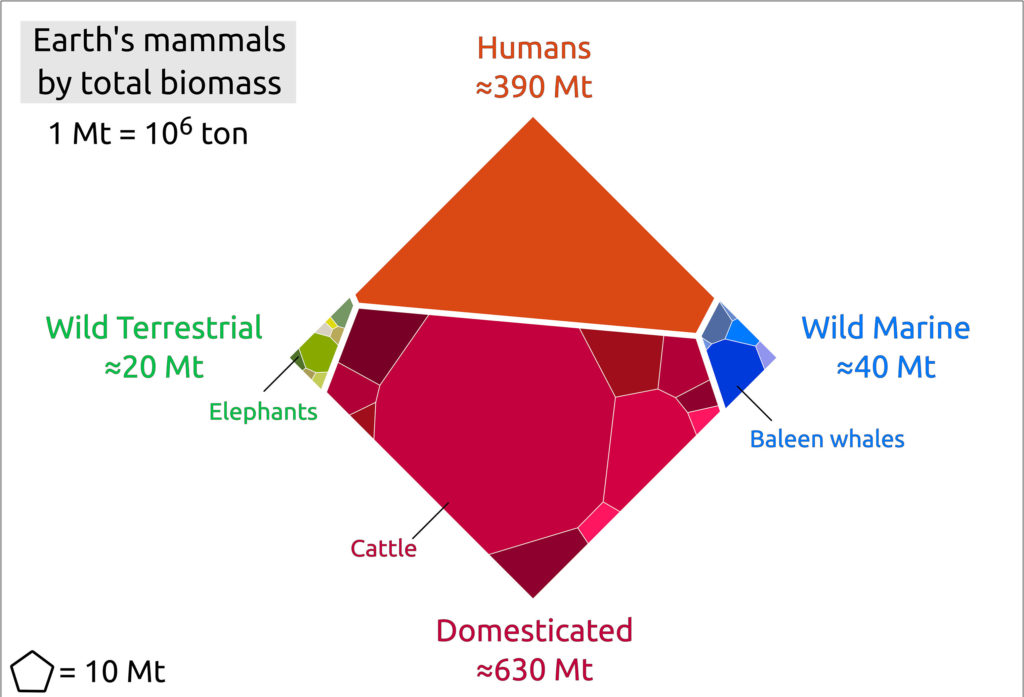

Just as a cancer-afflicted organ swells to gross proportions, so too has the human “organ” on the planet swollen to a dangerous size. The figure shared in Episode 7 helps illustrate.

From Greenspoon et al. 2023: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2204892120

Humans and our domesticated extensions have crowded out the wild mammals just as neighboring organs can be squeezed by an engorged tumor. This is not a healthy state of affairs: the tumor that has swollen humanity is forcing other life into a struggle for survival—putting extinction on the table.

A cancer-enlarged organ does not reflect the true nature of the organ. Likewise, modernity-enlarged human population does not reflect the true nature of humanity. Modernity has taken us far out of our ecological context.

Humans are NOT the Cancer

A common reaction to the foregoing cancer comparison is to assume that I am labeling humans as a cancer, which might be off-putting. That’s not my intention. Humans are not the cancer. Humans were afflicted by the cancer.

So, try not to take the cancer comparison personally, which only eclipses the message. Attach the negative qualities to modernity, not to humanity. It is a faulty program—or operating system—that happened get installed in (some) humans, and then spread. Let’s not blame the victim. As before, we don’t hate the pancreas because it had the misfortune to contract cancer. We appreciate that a healthy pancreas has a role in a healthy body. Similarly, humans have an ecological context: a generative role in a healthy community of life. That’s the only way we could have evolved into being: by occupying a role in the whole.

Hard to Stop

One other attraction for me in the modernity–cancer analog is that both are incredibly hard to stop—especially once metastasized. Modernity is so firmly rooted in present-day human cultures across the globe that it is fully entrenched and in control.

I have compared modernity to a technological boat on a raging river headed for a waterfall. Once gripped by the currents, the boat of modernity has essentially no choice but to go over the waterfall, because that’s what unsustainable fabrications must do.

Most of humanity is riding in the boat, and many enjoy the thrill of the ride. But humans need not go down with the boat. Abandoning ship is an option—albeit an understandably scary one.

Metaphorical Misfits

While sometimes very helpful in facilitating understanding, no analogy or metaphor is perfect. Here are a few things that don’t work in this case.

Flaw #1: Growth

Growth is identified in both analogs as an essential problem. Indeed, runaway tumor growth is unsurvivable, just as continued growth on a finite planet is not an option. But being too literal about the analogy might suggest that halting modernity’s growth so that we might hang out at the current level—tolerating a static tumor—would be just peachy. But that’s inaccurate. The scale itself is an enormous problem, as is modernity’s utter reliance on non-renewable materials, its failure to use materials processed by the community of life, and its failure to establish a rich set of ecological, reciprocal relationships in the web of life. So, just stopping growth is not a “solution.” The ecological nosedive would continue, only halting its acceleration.

Flaw #2: No Perks

Another analogy failing of sorts is that cancer tends not to bring with it a collection of perks that we enjoy, as modernity does. Modernity is more pernicious, in this regard. Granted, all those Likes in modernity are directly tied to the damaging Dislikes (Episode 10), so we can’t choose to keep the Likes in isolation. But still, the analogy would be better if cancer brought with it some perks. For instance, what if having cancer meant not needing to sleep anymore? Or what if everything tasted like chocolate? What if a feeling of euphoria accompanied the experience? Then we’d have a better match to modernity—perhaps with addictive qualities as well. Lots of people accept modernity because the Likes are so attractive, despite its terminal and devastating impacts. Maybe people would accept the inevitable early end of cancer if it meant enjoying the perks for a short time. No?

Flaw #3: Modernity Less Deadly

Finally, metastatic cancer runs its course by killing the host. Humanity is not as strictly, biophysically tied to the fate of modernity. Modernity is therefore less deadly, in this regard. Modernity has no choice but to end, although it seems very likely to me that humans will survive the trauma and come out the other side experimenting with new (and/or old) ways of living, necessarily in closer connection with local ecological realities. The diagnosis is terminal for modernity, but not for humanity. Again, it is crucial to be able to split these entities apart from each other.

Closing

Next time we’ll take stock of how we might react to this metastatic diagnosis. It’s heavy news.