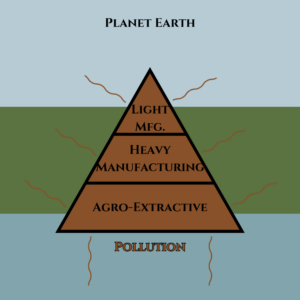

Like the economy of nature, the human economy has a “trophic” structure. In nature, nutrition and energy flow from plants to herbivores to carnivores, with each of these comprising a trophic level of the ecosystem. In the human economy, materials and energy flow from agriculture and other extractive activities to heavy manufacturing to light manufacturing. Both economies include service providers, such as pollinators in nature and the transportation sector in the human economy.

This ecological conceptualization of the economy provides the foundation for the trophic theory of money. It states that money originates from increases in mouths fed per farmer, which frees people up to engage in other economic activities. It further posits that real economic growth is not possible without growth in the agricultural and extractive activities at the trophic “base” of the economy.

Most research on the trophic theory of money focuses on agriculture. The agricultural sector plays a unique role in our economy because: a) food surplus is an absolute prerequisite for other economic activities, and; b) it has consequently marked the origins of money in civilizations throughout history.

Food may come first, but we didn’t build our $105 trillion global economy on agriculture alone. Agriculture could not produce the unprecedented quantities of food it does today—3.1 billion tons of cereals alone in 2022—if it weren’t for another unique natural resource: fossil fuels. Unlike food, humans don’t need fossil fuels to survive. However, our modern way of life does.

Nothing Quite Like ‘Em

Fossil fuels are our modern economy’s “great stimulant.” Whatever sector they touch, be it agriculture, construction, or entertainment, undergoes a boom. We tend to attribute this boom to increased productivity. Fossil fuels enable the production of more output with a given amount of input, such as labor or land. Yet fossil fuels’ true power is that they allow us to procure more input. With the use of fossil fuels, we clear more forests, drain more wetlands, and dig deeper into the Earth’s crust to extract more biomass, minerals, and—you guessed it—fossil fuels.

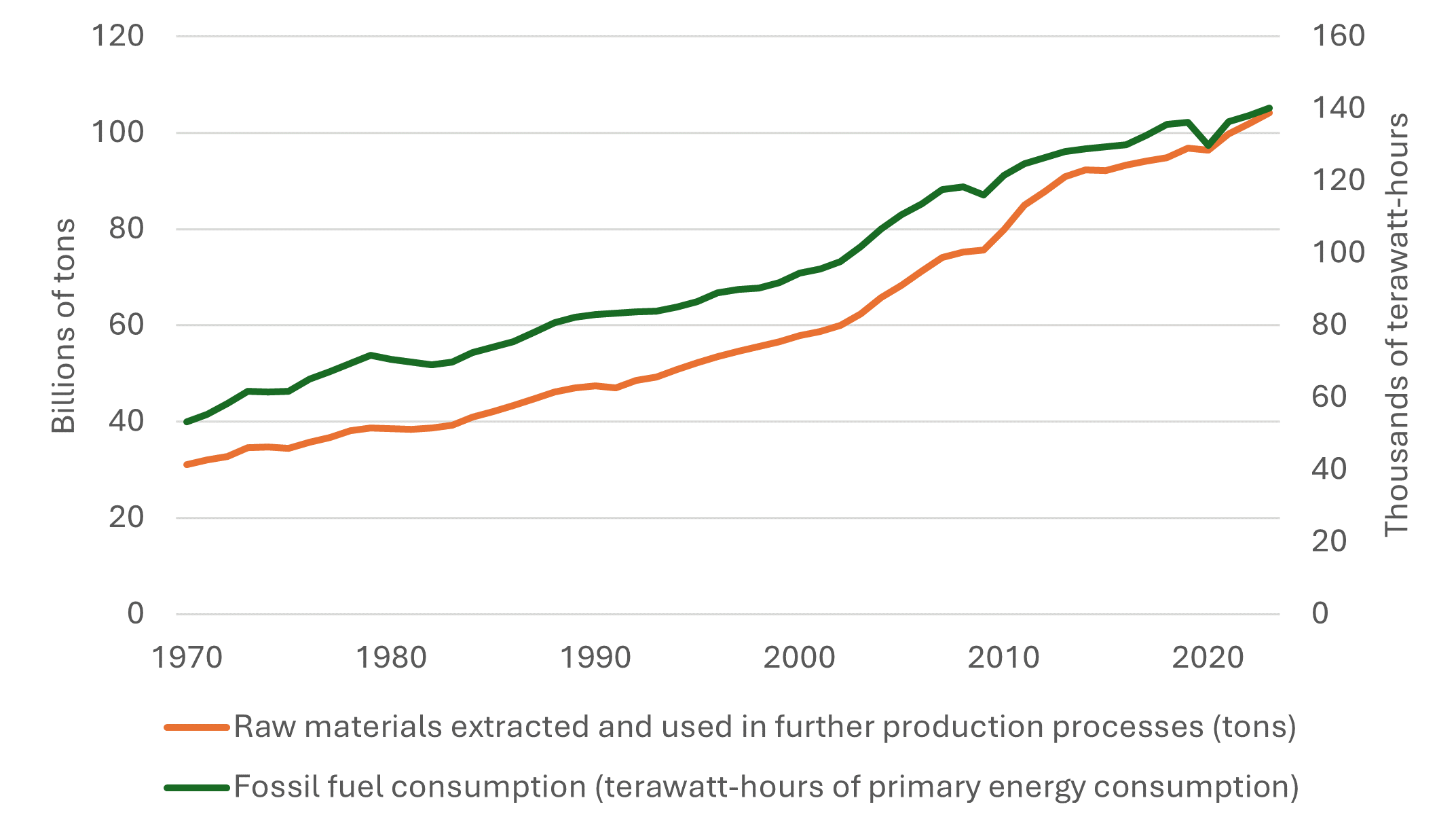

Raw materials extracted and fossil fuel consumed over time. (Raw materials extracted comes from MaterialFlows.net, and fossil fuel consumption comes from the Energy Institute.)

In fact, the first mechanical process to harness the power of fossil fuels was invented to extract more fossil fuels. In 1776, James Watt designed the first coal-fired steam engine to pump water out of coal mines. Then came the Industrial Revolution.

The rest is history. From 1970 to 2020, global fossil fuel consumption increased by a factor of 2.5. Global extraction of materials more than tripled.

Increased fossil fuel consumption and material extraction have been accompanied by global economic growth, as measured by real GDP. Additionally, the price of fossil fuels, especially oil, has a heavy influence on the economy. Spikes in oil prices are one of the most cited causes of inflation.

A Trophic Perspective

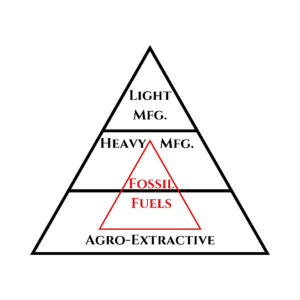

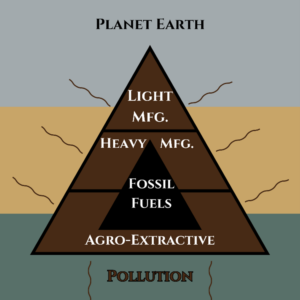

Fossil fuels are at the core of the modern economy and are sourced from the bottom two trophic levels.

So, how can we conceptualize the unique role of fossil fuels in our bloated human economy using a trophic, ecological lens? I propose the figure to the right to demonstrate both the sources of fossil fuels and their stimulating effects on other economic sectors. Some fossil fuels are extracted from the Earth and used in their raw form. For example, most of the coal used in power plants is “feedstock”. These unrefined fossil fuels occupy the base of the economy, with agriculture and other extractive activities. Other fossil fuels are refined via heavy manufacturing processes before being consumed. For example, crude oil is refined to produce gasoline. Gasoline and other refined fossil fuel products occupy the second trophic level.

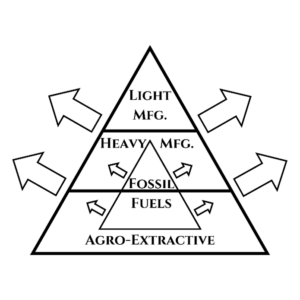

Human economies existed before fossil fuels as smaller ecosystems; smaller and slower-growing triangles. When fossil fuels came on the scene, they took up residence at the core of the economy. Growth of this core stimulates even more growth in other sectors, as illustrated below. Given agriculture’s unique role as a precursor of other economic activity, I will use this sector as an example of fossil fuels’ effects. However, almost every sector in today’s economy has been transformed by fossil fuels.

Fossil fuels are at the core of the modern economy and are sourced from the bottom two trophic levels.

Growth of the fossil fuel core leads to even more growth in other sectors and, consequently, the overall economy.

Fossil fuels’ biggest impact on the agricultural sector stems from the use of natural gas in industrial fertilizer production. Industrial fertilizer was first mass-produced in 1914 using what came to be known as the Haber-Bosch process. This invention enabled the Green Revolution, a boom in agricultural production that took place in the latter half of the 20th century, starting in Mexico and India. From 1961 to 2010, cereal yields per acre increased by 217 percent in Mexico and 183 percent in India. It is no coincidence that the human population has more than quadrupled since 1920.

We often attribute the Green Revolution to the spread of high-yielding crop varieties. Yet these varieties typically require industrial fertilizer application. The Haber-Bosch method, combined with mechanization and pesticides derived from fossil fuels, have represented a massive and unsustainable injection of fossil fuels into our food system. Today, the production of one food calorie in the United States requires 2.7 fossil fuel calories.

Fossil fuels have also had a massive stimulating effect on our manufacturing and service sectors, as well as our burgeoning digital economy. Imagine for a moment what would happen if we lost access to this resource—if we reached an energy cliff, perhaps. Our unwieldy economy would likely collapse, or snap back on itself like a taut rubber band.

A Splash of Color

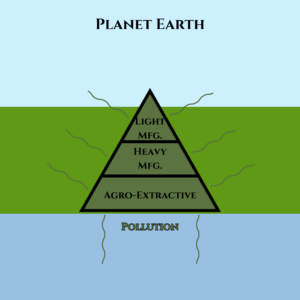

A small economy that avoids the extraction of non-renewable resources and prioritizes recycling and composting could emanate so little brown as to verge on green.

Let’s add some color to our model. In Supply Shock, Brian Czech points out that there’s no such thing as green growth; only “less-brown” growth. Of course, producing a unicycle is less environmentally harmful than producing a Hummer, but that doesn’t make it environmentally “friendly”. The unicycle is composed of steel, aluminum, rubber, plastic, etc. And with an injection of fossil-fuel energy, voila, these materials combine to produce a new unicycle that makes you feel environmentally benevolent.

This fossil-fuel injection is responsible for most of the environmental harm caused by making the unicycle. Unicycles created without fossil fuels would likely consist of wood, leather, and iron, all manually extracted and processed. This would be far more labor-intensive, and, without fossil-fueled trade, producers would be more cognizant of local resource limits. The result would be fewer resources extracted and fewer unicycles coming off the production line (and forget about Hummers).

Even in the absence of fossil fuels, an economy can exceed its ecological limits, but this has never occurred at such a global scale.

Fossil fuels have not only a stimulating effect but also a browning effect on other sectors. A relatively small economy could hypothetically contain so little brown that it verges on green. In this truly sustainable economy, we would not “liquidate” renewable resources. This means we would not consume them faster than they can renew themselves, and we would facilitate their renewal by composting. We would leave non-renewable resources in the ground wherever possible, and otherwise we would recycle them. In this way, we could keep pollution to levels that can be absorbed and converted by a healthy ecosystem. This is how we would achieve a steady state economy.

Many human economies had browned significantly even before the advent of fossil fuels. People generated pollution by burning organic matter, manually smelting metal, and mismanaging human waste. Local resource availability, however, imposed limits to just how brown an economy could get.

Pollution Beyond the Limits of the Here and Now

In the 18th century, Great Britain bumped up against local limits to growth when it depleted its supply of timber, which it used to cook and heat. The country broke through the ceiling, however, when it turned to coal as an energy source. The energy from coal and other fossil fuels was harnessed over millions of years by prehistoric organisms in the process of photosynthesis (at the trophic base) and consumption (higher trophic levels). By using fossil fuels, we are reaching back through time to access more of that energy than the Earth can produce at any given moment. It’s the very essence of unsustainability.

This time-warping discovery spread, stimulating global trade and enabling innovations like the Haber-Bosch process. Economies around the world catapulted past their local limits to growth. As the use of fossil fuels spread, it multiplied the environmental impact of existing industries.

Once we inject fossil fuels into all our production and consumption processes, their cumulative direct and indirect effects serve to thoroughly brown the economy.

Returning to our previous example, agriculture used to employ sustainable farming techniques that consumed minimal resources and generated little pollution. The use of fossil fuels for mechanization and fertilizer production has thoroughly browned this sector.

The fossil-fuel combustion involved in these processes emits health-damaging and planet-warming air pollutants. However, pollution from fossil-fuel products used in agriculture is also devastating and often overlooked. For example, the nitrogen in synthetic fertilizer makes its way into the atmosphere as a potent greenhouse gas or into waterways as harmful nutrient runoff.

We also use fossil fuels in chemical processes to produce substances that did not previously exist in Nature. A prime example of these “novel entities” used in agriculture are pesticides. These chemicals find their way into our crops and into our bodies, usually without being properly vetted for their environmental and health impacts.

Fossil Fuels as Steroids

An apt analogy for the stimulating and “browning” effects of fossil fuels on the economy is that of anabolic steroids. Just like our economy under the influence of fossil fuels, individuals who use steroids experience immediate perceived benefits: their muscles grow, and their physical performance improves. Similarly, millions of people have benefited from the comforts afforded by our fossil-fueled economic activity.

However, the long-term use of anabolic steroids increases the consumer’s risk of a slew of health issues: liver damage, hormonal imbalances, and cardiovascular problems, to name a few. Likewise, the negative environmental effects of fossil-fuel use will eventually come to outweigh the benefits, making the human economy and the people affected by it physically and mentally ill. In many ways, we may already have passed this point.

When a heavy steroid user abruptly stops using, they can experience physical and psychological withdrawal symptoms and health complications. Similarly, an abrupt cutoff from fossil fuels would have dire consequences for humanity.

Yet an eventual cutoff is inevitable, as we burn through readily available fossil fuels and remaining supplies require more and more energy to access. What remains to be seen is how we will handle this transition. Will we stay under the sway of the illusion of limitless growth, till no body of water or plot of land or lungful of air is left untouched by our profligate economic system? Or will we choose the steady-state path, gently tapering off our steroid supply through intentional government policies and adjustments to our way of life? Only our actions will tell.