This is the eleventh of 18 installments in the Metastatic Modernity video series (see launch announcement), putting the meta-crisis in perspective as a cancerous disease afflicting humanity and the greater community of life on Earth. This episode looks at various reasons why renewable energy and recycling are not our way out of the predicament modernity has set out for us. It’s just a doubling-down that can’t really work anyway.

As is the custom for the series, I provide a stand-alone companion piece in written form (not a transcript) so that the key ideas may be absorbed by a different channel. The write-up that follows is arranged according to “chapters” in the video, navigable via links in the YouTube description field.

Introduction

This is the usual short naming of the series, of myself as a recovering astrophysicist, and the topic of this episode (why renewables aren’t the answer) as part of our effort to put modernity into context. I see this topic as a bit of a tangent to the main thread, but one that I think needs to be addressed.

A Past Enthusiast

I have a much more intimate relationship with solar energy than your average bear—or even the average “energy transition” advocate. Besides knowing the semiconductor physics inside out, as a hands-on guy I have experimented with various off-grid configurations of panels, built my own curve-tracer to explore partial shade effects, tried different battery chemistries, learned the ins and outs of four different charge controllers, tried different inverter types, performed extensive monitoring and analysis, etc. Plus, living an off-grid lifestyle connected me more viscerally to weather trends, and my energy haul (and expenditure) becomes more personal. I wrote a Physics Today article in 2008 on getting started, and various Do the Math posts (e.g., here, and here) relating to my experiments. Figure 13.15 in my textbook came from my system.

You could say that I have been an enthusiast, and have acquired a fair bit of knowledge and lived experience in the matter. My default starting position was that solar power was bound to be a huge part of our answer to things like climate change and peak oil. Well, it turns out that narrow solutions work perfectly for narrowly-defined or recognized problems. I will try to broaden the perspective in this piece, which has some overlap with A Climate Love Story and Inexhaustible Flows.

Cost of Climate Change Dominance

A primary focus on climate change means the solution becomes artificially straightforward: eliminate CO2 emissions. Solar, wind, EVs, and done! We are attracted to simple stories and tidy solutions like ants to sugar.

But elimination of climate change and CO2 makes only a small dent in the list of causes for the ecological nosedive presented in Episode 7, so that the sixth mass extinction steams right ahead even in a stabilized climate. Of course, we’re dealing with all the elements on the list all at once, and climate change just makes everything worse.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not a climate change denier. Some people only have one box for anyone who does not put climate change at the top of the list. If that’s you, please find more boxes. To me, the larger and more pervasive denial is that climate change is the main problem to be cracked—and via technology, of course.

But even on technical grounds, renewable energy fails to get us out of our mess. I won’t even address here the fact that electricity from renewables can’t obviously satisfy our manufacturing and transportation needs, because that’s not even the appropriate goal, for me.

Materials Demand

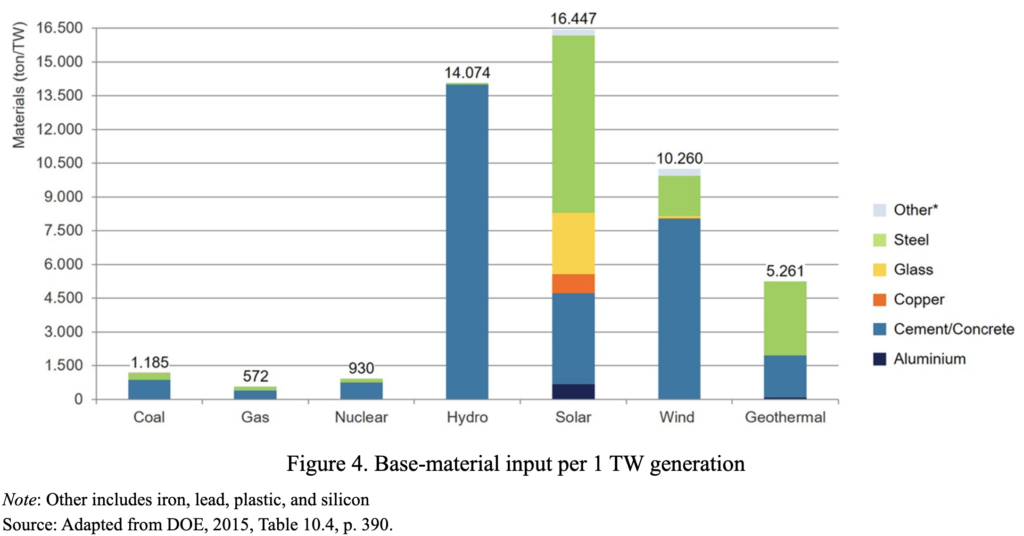

A very important and real concern is that all renewable energy technologies require a lot of non-renewable materials. This is because they tend to be diffuse, low density sources energy, necessitating large amounts of “stuff” to capture and convert. Below is a figure that represents data from the Department of Energy’s Quadrennial Technology Review (Table 10.4).

From Schernikau et al. 2022.

In terms of concrete, steel, copper, glass, and aluminum (not counting the fossil fuel mass itself), renewable energy requires an order-of-magnitude more material per unit of electrical energy delivered than does fossil fuel combustion. This translates to never-ending mining, manufacturing, pollution, and all the associated ecological costs. It’s not a build-it-once-and-done game.

Renewable energy is therefore not actually renewable, since it depends crucially on non-renewable materials. If becomes essentially irrelevant that sun and wind keep coming “inexhaustibly” when the weakest link is non-renewable, and therefore dictates the story. An analogy would be saying that fossil fuel combustion requires oxygen, whose supply is effectively unlimited, so fossil fuel combustion is unlimited? Not at all! One has to look at the limiting factor, not single out the one part of the system that is not a limitation (like sunlight or wind). It’s evident, right?

A solar panel made of something that regrows itself (like plant matter) using elements in ecological circulation would satisfy me in terms of renewability. I’ve just managed to describe a leaf, minus the electricity.

The Genius of Life

This is part of what is so remarkable about life. It has figured out how to do all the amazing things it does based on a small set of elements found in common circulation on the surface of the earth. No mining is required. Recycling is essentially perfect, utilizing a vast web of life to carry out the entire process—from microbes to fungi to worms to insects to birds, etc.

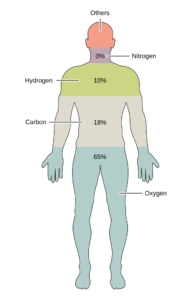

In an earlier post called Inexhaustible Flows, I quantify the elements involved in life, which for this abbreviated treatment can be represented via this figure.

From bottom, oxygen, carbon, hydrogen, and nitrogen make up 96% of human mass. From Wikimedia Commons.

The four labeled elements that comprise 96% of our mass derive from air and water! The carbon comes from plant matter that grabbed it from airborne CO2. Nitrogen is “fixed” out of the air by plants and bacteria before ending up in our bodies. This is a truly incredible trick, huh? Imagine making our clunky cars, computers, submarines, cities, or solar panels out of mostly air and water. Yet life manages it.

The other elements amounting to any significance are calcium, phosphorus, potassium, sulfur, sodium, chlorine, and magnesium: all in broad circulation. As I mentioned, the recycling program is essentially 100% efficient, and goes for millions upon millions of years.

Life does not have much truck with elements that require mining like copper, aluminum, silicon, gold, nickel, cobalt, neodymium, lithium, silver, lead, titanium, and so forth. Our sad inventions use the wrong stuff, don’t last long, leave a waste stream that is not useful (and in fact often harmful) to life, and will not persist on ecological timescales. Where is the true genius, I ask you?

Recycling Limitations

One common reaction to the figure above showing the heavy material demand of renewable energy is: yeah, sure, but you only have to do it once and then it’s recycling from there on out.

First, don’t dismiss the massive initial build-out. You can’t recycle what’s not already in place, and we’re talking about an enormous material outlay to provision modernity with its desired power from renewable resources. In fact, the current “breakneck” pace of solar energy installation is still an order-of-magnitude smaller than it would take even to hold steady at today’s energy appetite based on routine attrition of hardware after a few decades. The effort would require new mines, new deforestation, new waste, new manufacturing and associated pollution, and new habitat loss (and threat of extinctions) from situating these massive infrastructures.

Second, saying the word “recycling” is not a “get out of jail free” card: nice try. In the real world, retrieval is not perfect. Some stuff gets destroyed/scattered, trashed, stored, or otherwise is unavailable for collection. Then not all the collected material will be recoverable. Even an unprecedented, fantasy-level 90% end-to-end recovery results in less than half the original resource after just 7 cycles, and less than 10% after 22 cycles. It’s not indefinite. It prolongs, but does not solve the issue, on strictly technical grounds (leaving aside ongoing ecological erosion for now).

Turbines and panels last a few decades before requiring replacement, which means that recycling peters out on the timescale of a few centuries at best. Compared to the time our species has been on the planet, or even the time since our agricultural departure from ecological living set us on this path, a few centuries is hardly anything. Because it depends on “exotic” (mined) materials, modernity will starve itself in relatively short order even if everything else went swimmingly—which it isn’t.

What Do We DO with Energy?

This is the real question at the heart of the matter. We use energy to cut down forests, clear land for agriculture, mass-murder plants and animals with herbicides and pesticides (I’m not being melodramatic: “-cide” means murder, as in homicide, suicide, and genocide), build cities, highways, dams, cars, gadgets. We use energy to mine materials, spew the tailings, manufacture goods, and release all manner of chemical contamination that the community of life has no provision to process. What we do with energy is produce all those “Likes” from the previous episode, manifestly tangling us into a raft of Dislikes.

The plants and animals know what we do with energy. We dominate the planet and drive ecological health into the ground. They are not cheering ambitions of an energy transition to solar, wind, and electric vehicles. To them, the damage is every bit as bad no matter the engine: the pressure does not let up. The sixth mass extinction barrels on.

The driving attitude is: it’s all ours, dammit! We own the world and can do anything we want with it for our short-term gains. I mean, GDP won’t take care of itself, will it?

You see, it doesn’t matter what form our energy technology takes. What matters is our cultural attitude that sets the agenda. It’s our intent and disregard for the community of life. The next episode will address the related matter of human supremacy.

Intent Matters

Dennis Meadows, of Limits to Growth fame, put it this way (paraphrasing, and emphasis mine):

If a man is coming at you with a hammer, clearly intent on doing you harm, the technology he holds is of secondary importance to you. Instead of a hammer, it could be a gun, knife, bat, mace, or staple gun. The thing that matters most to you is his intent to do you harm.

As we rush at the community of life clutching our technology, we show every appearance of an intent to do it harm. It won’t matter whether we destroy the living world with fossil fuels or solar panels: we are more than capable of getting the job done either way. Before we get too far along, though, I suspect that the deteriorating web of life will create cascading failures that end up making humans victims, too, and pulling the power cord to the destructive machine. Only then would some people accept that ecological ignorance—paired with technological capability—has dire consequences.

Obligatory Titanic Metaphor

One of my favorite Onion headlines is World’s Largest Metaphor Hits Iceberg. The Titanic’s main problem wasn’t that it had a coal-fired engine belching CO2 instead of a sleek bank of lithium batteries charged by solar panels. The problem was the full-steam-ahead, invincible, hubristic attitude of “owning” the ocean. It was the intent, not the technology. Ramming the iceberg wasn’t the coal’s fault. “Renewable” drive would be just as capable of meeting the same fate.

Switching the engine powering modernity to a different technology does not fundamentally alter the situation.

Imagine this conversation on the bridge of the Titanic:

First Mate: Sir, we’re heading straight for a giant iceberg whose encounter even this ship can’t withstand. Oh, and for some reason our engine is slowing and we’re losing steam.

Captain: OMG: if we lose steam, we won’t make it to New York in record time. All hands to restore speed!

Ummm. Did you hear the first part? We’ll break a different kind of record by ignoring the more fundamental peril. Losing speed is the best thing imaginable in this circumstance.

Cease What, Exactly

Of the activities listed above that we use energy to do, tell me which ones we plan to cease under renewable energy. Will we stop cutting down forests, stop clearing land for agriculture, stop murdering plants and animals, stop building cities, highways, dams, cars, and gadgets? Will we stop mining materials, spewing the tailings, manufacturing goods, and releasing all manner of chemical contamination into our living world? Will we stop pursuing the “Likes” that are responsible for all the Dislikes (last episode)?

Sure, eliminating CO2 emissions and reining in climate change would be a great victory, but it doesn’t get us out of trouble. The intense ecological pressures would still be in place.

I mean, think about it: isn’t the whole point of renewable energy to be able to keep doing these things—business-as-usual—but without CO2 emissions? Isn’t the point to keep modernity fully powered? Just be aware that doing so keeps our boot on the throat of the community of life so it can’t breathe. Doing so keeps the sixth mass extinction basically on track, uninterrupted—though perhaps not as quickly or warmly.

Ask yourself the question this way: do the plants and animals cheer heartily to learn that we have a plan to steam along using a snazzy new engine? I don’t see why on Earth they would.