This is the tenth of 18 installments in the Metastatic Modernity video series (see launch announcement), putting the meta-crisis in perspective as a cancerous disease afflicting humanity and the greater community of life on Earth. This episode confronts the bargaining plea: can’t we keep all the stuff we like about modernity and just get rid of the stuff we don’t like?

As is the custom for the series, I provide a stand-alone companion piece in written form (not a transcript) so that the key ideas may be absorbed by a different channel. The write-up that follows is arranged according to “chapters” in the video, navigable via links in the YouTube description field.

Introduction

This is the usual short naming of the series, of myself, and the topic of this episode (can we keep the “good” and eliminate the bad?) as part of our effort to put modernity into context.

Trappings of Modernity

We use this term, trappings, to indicate the outward signs of success: the bells, whistles, conveniences, and conspicuous consumption of our culture. But it’s a pyrrhic kind of success: superficial; itself leading to failure. I like that the word also has “trap” built into it. Modernity offers many alluring perks that act like monkey traps: we grab the banana and won’t let go, even to our detriment. The hidden costs become too great to bear, in the end.

Back to the Stone Age?

My conclusion that modernity will turn out to be a failed experiment—ultimately unsupported by the forces of ecology and evolution—trips a circuit breaker for lots of people. Do I propose a return to the Stone Age? Fury wells up at all the lost benefits such a reversion would entail. What a monstrous proposal!

Firstly, I am making no proposals: just pointing out that modernity can’t be the answer, and we don’t possess the power of choice to maintain something that is fundamentally unsustainable. We similarly can’t decide to ignore gravity and float through the room.

This anomalous period of rapid inheritance spending in a one-time draw-down of ecological health has given us the false impression that we can do anything we want—that it’s all a matter of choice. We therefore live in a fleeting fantasy world in which our mental models don’t match the broader reality. The temporary excess of this moment makes us poor judges of what’s possible in the long term.

Our Likes and Dislikes

Let’s start a table—admittedly incomplete—of the things we like, just to build a flavor. We’ll also add a column of the downsides: things we dislike and might want to eliminate. The columns are not matched, row-for-row, but constitute two independent lists.

| We Like | We Dislike |

|---|---|

| Medical Care | Pollution |

| Food Ease | Deforestation |

| Transportation | Biodiversity Loss |

| Climate Control | Extinctions |

| Hot Showers | Climate Change |

| Smart Phones | Landfills |

| Video Entertainment | Market Domination |

| Computers/Internet | Traffic/Parking (overcrowding) |

I’m sure you could add to both columns (science would be an appropriate Like, for instance).

The Big Perks

An aside on the first two Likes… A common one is that “I and/or someone I know and love dearly would not be here without modern medical intervention.” I can say nothing other than I am glad to have you/them with us, still. I happen to love and admire people (not a misanthrope). Eight billion people, in fact, are awesome. Just not when all here at once. Spread it out, maybe, and then we can talk about more than 8 billion, distributed over time. But we can’t change the facts, and I do not propose harming any human already here through no fault of their own. We need to get through this crunch and learn from our mistakes.

The next big perk is access to food. About 5.5 billion people in the world enjoy food security, having enough money that food is not particularly problematic to obtain. Fed people naturally see this as a good thing.

Political Leanings

Political movements sometimes focus on both columns, but it seems more attention goes to “what do we want?” (more perks) than to eliminating negatives that are more conveniently pushed aside and ignored. Campaigns tend to work better on positivity and promise than on the ills that need to be reduced or eliminated. It’s worth being aware of this bias in the context of Likes and Dislikes.

A Brilliant Plan!

Here’s how a lot of people work (myself included, at times):

Hey, I know what to do. I’ve given it a whole two seconds of thought, and it seems to me that we just need to dump all the bad stuff and keep the good stuff! Because nobody likes the bad stuff, right? So why keep it around?

I’m sure nobody has ever considered this before, so thanks for that!

As obvious as this is, there must be a reason we still have the bad stuff. If it were easy to jettison, it would have been done long ago. For something this important, it does not serve us to be glib, offering only “why can’t we just…” sorts of poorly-examined proposals.

Double Elimination

But, let’s entertain this simple proposal for a moment. What if we became truly disgusted with the “Dislike” items on the list above and fully committed ourselves to complete elimination of those problems: a moratorium on the damaging activities. What is the result?

We eliminate all the things in the “Like” column in the same swoop. The bottom line is that we simply don’t know how to have one without the other—or we’d already be doing that! Yet, here we are, not only suffering the same old thorns, but often seeing them get thornier and adding new ones. The Dislikes have stubbornly remained problematic, despite major concerns for decades or centuries.

Our culture has instilled a frightening degree of faith in technological capacity. We tell ourselves, with fevered conviction, that we can do anything we set our unlimited minds to. What absolute rubbish! Do these people even hear themselves? It’s delusional, yet ubiquitous in our culture.

Two Sides of a Coin

The Likes and the Dislikes go hand-in-hand. They are a package deal; two sides of the same coin. If you don’t like the fact that your coin has a back side, shaving it off still leaves a back side. Want to live but without the inconveniences of eating, sleeping, pooping, or dying? I’m sure if you just think really hard with that precious head of yours…

Pick a Team!

The crux of the matter is: if these pros and cons are inseparable, then liking the Likes amounts to liking the Dislikes. Conversely, if you more strongly dislike the Dislikes, you effectively dislike the Likes. Pick a team: accept/embrace the Dislikes as part of the Likes (along with its necessary self-termination), or be prepared to set aside the things you thought were good because in full consideration, they are actually bad on the whole, when considering the full context. Unfortunately, we have been well trained to isolate, reduce, simplify and decontextualize into discrete problems that have tidy solutions. It’s easy to do when ignoring the complications from the wider—but ever-present—world, and these tendencies do not serve us well.

Inseparable?

The above framing contains what some may consider to be a “big if,” which may be less than obvious. Consider, however, that we have a world of evidence for how the Likes rely on the Dislikes, but lack any evidence of supporting one without the other. Also, wishing them to be separable has no effect on the reality of the situation.

Asymmetric Situation

Acceptance of the bad stuff might be okay if it didn’t undermine life on Earth, ecological viability, and set up a sixth mass extinction. In a cost–benefit analysis, the relative magnitudes are important. But more pointedly in this case, tolerating the Dislikes eventually leads to a collapse that destroys the Likes anyway. When it comes to ecological health on one side and human material comforts on the other, consider that one absolutely needs the other, while the reverse is certainly not true. We don’t really get to choose.

A Tangled Diagram

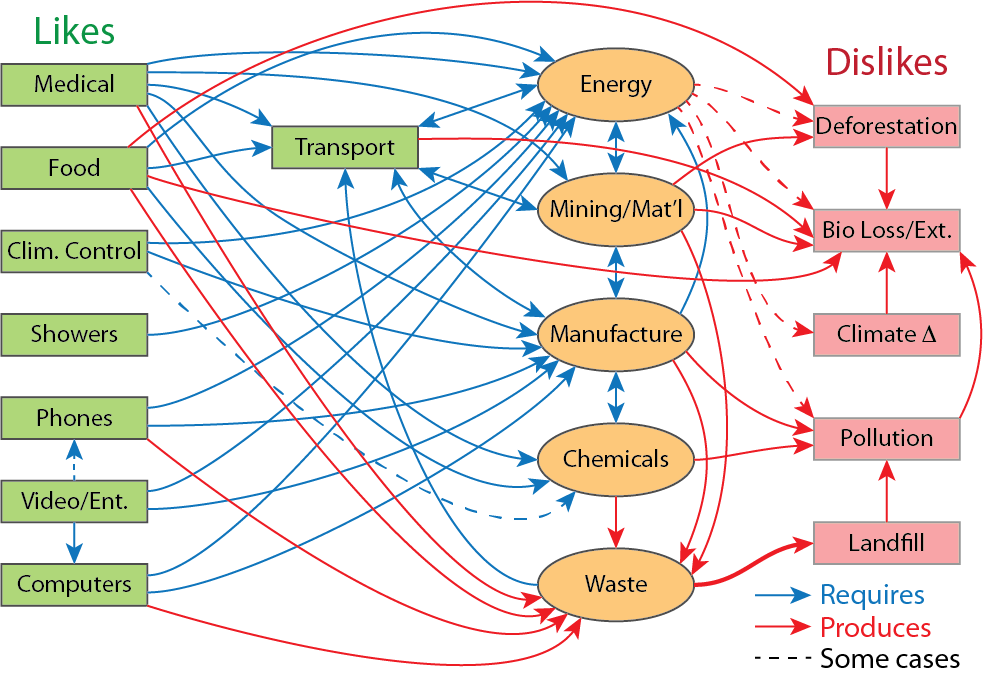

When I drafted this presentation, my first instinct was to make a table: what requirements (dependencies) do each of the Like items require of the world, and how do those trace to the Dislikes? Other than hitting on a nearly universal theme of materials (thus mining), energy, waste, and pollution, I recognized that it’s a much more tangled story than a table can show. So, I came up with this crude diagram.

Every Dislike—such as biodiversity loss and extinctions—is traceable to the Likes. While the diagram is not perfect, every arrow has an explicit and reasonable rationale. Blue arrows are dependencies/requirements (sometimes double-ended) and red arrows are products. Dashed ones indicate “sometimes true” conditions. For instance, many forms of energy contribute to climate change, but not all do—at least not directly.

For all its apparent complexity, this spaghetti diagram is vastly oversimplified: the real world is more tangled, still. For one thing, I left many possible arrows off whose presence I’m sure readers could justify. Yet, it need not be perfect to make the overall point.

Process of Elimination

If wanting to get rid of a Dislike, any arrowhead pointing to it has to go as well, and whatever that arrow connects back to is eliminated, curtailed, or otherwise impacted. Then, any arrowheads connected to that entity will likewise be impacted.

For example, if wishing to eliminate deforestation, then agricultural clearing of land is no longer possible. Materials collection—whether forest products or mining—involves land use and deforestation. Some energy resources must clear land to operate. If prohibiting deforestation from mining, the resulting eliminations ripple into impacts on energy, manufacturing, transport, and agriculture. From here, every Like is impacted—which is to say that every Like has a route to deforestation (most frequently through materials and energy).

Key Notes

Two things jumped out at me after completing this diagram. One is that climate change is perhaps the easiest to eliminate. Only one arrow points to it, from energy, and its a dashed one, at that. Eliminate fossil fuels from the energy mix and the primary driver of climate change goes away. We know this already, and this simple observation has led to the dream of replacing fossil fuels with “renewable” energy. The fact that climate change is the easiest of the Dislikes to eliminate might have some bearing on how much attention it gets. As intractable as it seems, it’s the simplest of the lot—which should give us some pause.

The other alarming outcome is how many roads lead to biodiversity loss and extinction. Eliminating this Dislike quickly tears down the infrastructure of modernity and kills the Likes. This is, to me, seems to spell game over for either modernity or ecological health (and thus modernity).

Material Reflections

This section was part of the original slide set, but was eliminated before recording for time reasons. I leave it here, and will touch on this again in future episodes.

Modernity requires material elements that are, in an ecological sense, “not of this world,” in that the materials are not woven into the web of life, integrated into the various nutrients in circulation. The community of life has no business with these sometimes harmful agents. Meanwhile, the requirements of modernity rip up habitat and deliberately eliminate “pests” who are “not of” our artificial and temporary world.

As you look around and walk through life, ask if the various materials and practices you encounter tuck into the web of life. Does the community of life embrace these things and know how to incorporate them into its practices? Or, are they “alien” elements that are “not of the ecological world?” Has evolution built built a community around these presences, or are they temporary intruders with no place?

But Renewables and Recycling?

This section was also eliminated from the video, but is left here as a bonus. The next installment will be devoted to this topic. Here, I offer a brief treatment. First, “renewables” and “recycling” are just words that are far short of being magic wands capable of making problems disappear. Limitations and new complications arise, of course.

Renewable energy flows tend to be diffuse and require a bunch of material to capture. This means mining, manufacturing, pollution, and all the usual, inseparable, negative consequences. Panels and turbines don’t last and need to be replaced—indefinitely. Copper mining would have to increase over today’s levels and stay up indefinitely, somehow (which it can’t do).

Besides perpetrating the widespread deployment of materials that are alien to the community of life, recycling only delays the inevitable, being well short of 100% recovery (must also repossess the distributed equipment, which will never be perfect). Even 90% end-to-end recovery—well beyond present practices—allows only 7 cycles before dropping below half the original resource, or 22 cycles before diving below 10%. We’re talking decades or centuries, not millennia. That’s an absolute flash in ecological and evolutionary terms. Modernity will therefore starve itself of its requirements—requirements that themselves erode the foundation of life. Where’s the win?

More to come on this topic…

Club of Life Board

Recall from the sixth installment the concept of a Club of Life, in which we are lucky to be members. Imagine that a review board is assembled from the biodiverse community of life (the Committee of Life?): plants, mammals, birds, amphibians, insects, etc. You approach the board with a proposal for one of your “Like” items, and have to make the case.

Let’s say that you want advanced medical care. The pros are:

- Longer lives for humans (at least for those who can afford it);

- A larger, healthier human population (due to lowered mortality);

- Greater potential for innovation and engagement in the market economy.

Board: Hmmm. Okay, what will it cost?

- Mining, and its associated deforestation, land use, mine tailings, introduction of “alien” materials;

- Energy, which is either fossil fuels (thus CO2 and climate change) or renewables which means land use, mining, manufacturing, pollution, waste;

- Waste, in the form of a mountain of disposable, individually-packaged, hermetic implements—plus the stream of “normal” waste from hospitals, for instance;

- Chemicals: the pharmaceuticals get into the environment, not to mention the chemical waste from their creation and the manufacture of all the medical paraphernalia;

- Pollution into air and water and soils from the medical industry and associated manufacture.

Oh, and we may be forgetting some of the costs because we’re simply unaware of the impacts of what we do, if you can imagine we might be so ignorant and careless! Aren’t we adorable!

The Board: And tell us again how this proposal benefits the community of life, whom we represent?

Well, we’re members of the community of life and the benefits we enumerated below apply to us, so that’s good, right?

Board: Sure, there’s some sense in that, and we can all celebrate lives well-lived. But given your track record and portfolio of activities, it looks like a net negative to the entire community. More healthy humans engaging in your market economy seems to be the last thing we, as a whole, need in the interest of distributed access to life. We’re supposed to all be in this together, right? Humans are not somehow separate from the community of life. If humans always “win” in the short term at the expense of the rest, then we actually all lose—humans as well.

Unless you can demonstrate how this helps the entire community, and not just yourselves at the expense of the rest of us, then we’re afraid the proposal must be denied.

Viable Substitutes

If we had to admit that the Likes on the list are incompatible with long-term success of humans as part of an ecological community, it may seem overwhelmingly devastating: a huge loss of all that we’ve worked to achieve. Yes: I can definitely sympathize. I’m a product of modernity, too, and am accustomed to various expectations that seem to be unjustified and unsustainable, ecologically. I know too little of other ways.

But if our goals have been utterly ecologically unsustainable, then they have no future anyway. It’s not necessarily the case that humans are fundamentally rotten. We have just been conditioned by our culture to crave inappropriate things—things that have no permanent place in this world; things that are not supported by the broader ecology. Maybe any lamentation should be over the fact that we went down this dead-end path in the first place, rather than over the unavoidable fact that we must abandon the destructive path and pick a new one.

Reportedly, people approaching death tend not to regret the material things they didn’t acquire, but the more deeply meaningful relationships that they might have tended to more thoughtfully. Our fondest memories are of connections we make with other living beings, and may involve laughter, singing, dancing, loving. A fulfilling life involves unconditional support for and by the community: sharing in all directions for the fitness of both the individual and the whole. A sense of awe, respect, and gratitude are powerful and appropriate. None of these things necessitate the list of Dislikes caused by materials, energy, waste, and pollution in the way of modernity. As in the monkey trap, we simply closed our hand around the wrong set of Likes, and are best-advised to let go.

Importantly, we’ve managed to live without the problematic Likes/Dislikes package before—in fact for most of our time on this planet. I don’t want to come off as believing some delusional tale that we can live on love and laughter in biophysical detachment from the ecological foundation. Of course not. I’m simply suggesting that we might pursue more ecologically “normal” needs that have long-standing built-in support from the community of life.

Next time, we will tackle a bit of a digression as to why renewables and recycling are not going to get us out of this mess.