In our small farm we have a small herd of five mothercows and their offspring. The cattle graze approximately half the year and consume hay for half of the year. They have free access to a lightly forested area of 2-3 hectares in the winter and certainly enjoy nibbling on some blueberry bush, heather or pine trees but most of the feed will be hay. The hay comes from 8 hectares of very poorly drained cropland, where most normal cropping is not possible. In addition, we cut hay on some neighbours’ idle land.

A typical year we slaughter three calves around 7 months old, one heifer or a cow and one steer that has reached full size, i.e. 3-4 years old. ”One in-one out” is how I mostly explain why we will, in average, slaughter the same number of animals as what is born in every year. Many visitors seem to have a problem to understand this limitation (there are of course also those that object to any slaughter from an ethical perspective). It is an ordeal every year to decide who will live and who will die. We like our cows very much and it would be nice if they all could live, grow and develop the herd as well as their individuality.

We sell the meat in 10-15 kg boxes directly to consumers, most of them are the same every year, many live close by and see our cows. There is a big demand for meat so we could easily sell more. But the number of cows and the quantity of meat is determined by the availability of feed.

We could, like many other farmers over centuries, chose strategies to overcome this limitation. We could 1) buy or rent more land, 2) convert more of our land to pasture or cropland 3) buy feed or 4) increase the production on our land.

Buying more land (1) is a zero-sum game, it just means that someone else will have less cows or grow less wheat. We have converted some dense forest land to a silvo-pastoral area (2), i.e. a much more open forest so that there will be more ground vegetation (in most Swedish pine or spruce forest there is not much to eat for either cows or deer). Now, however, it is winter feed that is the limiting factor and we have no land that is suitable to convert to crop land – in addition, there are environmental reasons for not doing it. Buying feed (3) is just another version of buying more land, i.e. we would exploit more land to feed more cows.

There are several ways to increase the production (4), for sure. We could buy chemical fertilizers. But as we are organic farmers that is not really an option. I recently wrote a series of articles of the problems with synthetic nitrogen fertilizers. Nitrogen fertilizers is the main source of greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture and represent almost 5% of total emissions and is associated with many other environmental damage. We could buy manure, but that just means that we would deprive some other land of manure. We could also use all manure collected in the winter for the hayfields. As things stand now we use around half of it on the vegetables and orchards and half go back (after all the manure is “generated” there) to the hayfields. But if we took all manure to the hayfields we would have to buy manure to our vegetables, so it is about the same as buying manure or feed.

Improved drainage and irrigation are also ways to increase production. But it is hard to drain better because most of our land is next to a lake and the level of the lake regulates the possibilities for drainage, unless you build dykes and use pumps. Irrigation is expensive and hard to justify for growing forage – we do have irrigation capacity for one hectare where we grow fruits and vegetables, but those crops are worth ten to hundred times as much as forage.

We can re-seed the grasslands, something we tried with several methods. Unfortunately the wild boars really liked when we sowed a wonderful mixture of plants including carraway and chicory – they made a total massacre of the field, which had to be resown once more, but without plants that boars love. Some other methods for improvement such as feeding cows seed, surface spreading in wet weather followed by grazing and inoculation of the manure with clover seeds (sound sophisticated but just means tossing some seeds on top of the manure in the manure spreader) have given somewhat positive effects. We could also hunt the deer, the boars, the geese and other species that feed on the same land as the cows. We do try many methods to keep them out of the orchards and the vegetables and don’t shy away from hunting, but we see grasslands and our hayfields as shared ecosystems, where other species also can thrive.

Our predecessors would also manually harvest wetlands, road banks and any small space where grass grew and they collected leaves in various ways to get more winter forage. I am certainly not a very lazy person, but there are limits to how much hard work I can muster….

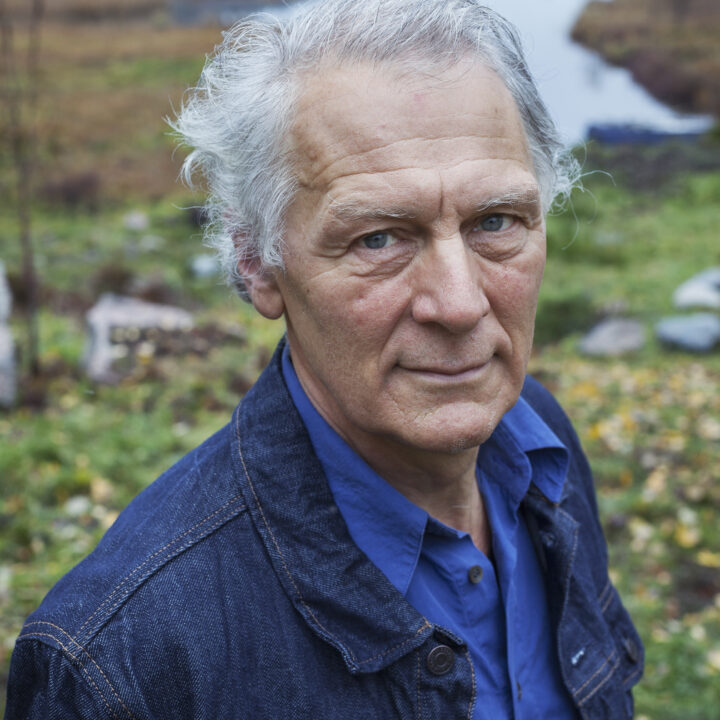

Hungarian Grey cattle at the puszta. Photo: Gunnar Rundgren

Anyway, we could increase productivity of the land in any of these ways in combination. Most methods require increased demand on or manipulation of nature, more labour or other resources. Some only require skill or imagination. Regardless of method, we would soon reach a new limit for the number of cows we could feed.

I guess that you by now have understood what I am aiming at by this story about our cows. In a nutshell, they demonstrate that there are limits, that there are multiple ways for humans to overcome those limits, but that those ways mostly increase our demand on the rest of the living, or limits their space of life.

For farmers, ranchers and pastoralists it is and has always been apparent that you can’t have more cows/sheep/goat/yaks/camels/horses than the carrying capacity of the land, and mostly the number of animals has been kept accordingly. If not, nature will take care of it. When I visited Mongolia some nine years ago we visited a family of herders. They told us that some years earlier the winter had been very hard and only three out of thirty cows survived and around half of the two hundred goats and sheep. The man in the family, Gonchigdorj, said laconically that “nature takes care of the balance, if there are too many animals, they will die during winter”.

Humanity has been extremely innovative and skilled and has constantly pushed the limit for how big share of the resources of the planet we are using. We have been successful in increasing the total biomass production in some limited areas, through fertilizers, irrigation and other management, and some “wild” plants also grow better as a result of the increase of carbon dioxide and nitrogen in the biosphere. Still, it is not apparent that global net primary production (i.e. has increased seen over a longer period, because we have also destroyed ecosystems or simply paved them over. What we have done is taking a larger share of this primary production (depending on whose figures you trust we take some 25% of the global primary production). By and large, we can’t change the fact that there are basic biological processes that limit the number of people (and cows!) and how much they can use.*

The origin of the word capital is Latin caput, meaning head, i.e. how many heads of cattle someone had. I don’t know if this origin of the word is also behind the notion that it is just normal and natural for capital to multiply – not only like cows but like rabbits or locust. To accumulate (by rent or profit) is the basic property of capitalism (it is part of the definition of the word) and a prerequisite for it to work. Compared to cows, capital is more versatile and can grow on more things than grass. Basically every part of the biosphere and Earth’s crust can be converted into products or resources in the metabolism of capitalism. My cows are lazy and eat the best grass that is close by first, before walking out in the swamp. In the same way, capital(ism) eats the low hanging fruits first; colonisation of other cultures; trade to exploit differences in cost of production and the use of enormous energy sources combined with technology to increase productivity of labour.

When it hits limits, as it always will, it directs it ingenuity toward other targets. Gradually, bigger parts of human society and humans themselves are converted into markets shaped by the needs of capitalism (I hope you don’t believe the foundational myth that markets are shaped by consumer demand?). Today, even knowledge, organs, disease and our trivial lives (through social media) are subject to capitalist exploitation. I guess that the re-awakened interest in space exploration also is an expression of this.

Sooner or later it will end. I don’t know if it will be because of suffocation by waste (also climate change is a question of waste), dwindling resources, ecosystem collapse or that the opportunities for further exploitation, aka accumulation of capital or falling profit rate, simply dwindles so that the system collapses by its inherent contradictions**. They seem to coalesce at the same time.

The long term opportunities for growth of my herd and the growth of global capitalism are the same. None.

* Perhaps someone now will say that we can use less if we don’t have cows. As a theoretical statement that is correct, but 1) the idea that we will save a lot of land by eating only plants is exaggerated (most of our land has no alternative use for plant production as it is too often flooded, we already grow vegetables and fruit on the land that is higher), 2) The saving of land by a pure vegan agriculture is much less than most people claim. In most cases, the land use will be higher with a pure vegan system than with a system with a moderate number of animals and 3) Most of the land used for grazing animals is not suitable for growing crops, even our hayfields which nominally are croplands are useless for crop growing as they flood too often. In any case, it really doesn’t change the fact that there are limits in the long run, even if we all were eating just wheat, beans and potatoes.

** The tendency of falling profit rates is no new discovery and it has been a centrepiece of Marxism, even if Marx never claimed that it was any kind of iron law. It was also noted long before Marx. Today, the closely related concept of “secular stagnation” has gained a lot of traction and the long period of very low or even negative interest rates combined with venture capital’s intensive search for new unicorns are strong indicators of that capitalism indeed has huge internal contradictions.