Perhaps you’ve heard: Autocracy is on the march. Not just in the obvious places like Russia, China, and North Korea. Democracy has been declining throughout the world for decades, sometimes gradually, sometimes suddenly, but invariably replaced by autocratic tendencies, politicians, and states.

What’s going on in places as far-flung as Hungary, Myanmar, and Nicaragua? Why, after the lessons of world wars, the Cold War, and nefarious autocrats from Pol Pot to Saddam Hussein, are autocratic and authoritarian regimes rearing their ugly heads? It’s not like today’s autocrats are universally despised by the people, either. In country after country, we find real or aspiring autocrats bolstered by grassroot waves of populism, often mixed with nationalism and racism.

In this third decade of the 21st century, is the golden age of democracy tarnished with a thickening patina of irrelevance? The answer may soon be a resounding “Yes,” if it isn’t already. Not just based on the obvious, empirical trends toward authoritarian rule, either. Rather, based on the concepts and principles of steady-state economics.

The argument herein is that democracy is rarely served in the 21st century by a growing economy, but rather by an optimal size of economy. When the economy is too small or mired in recession, the people demand change. That’s the scenario that brought us the likes of Adolf Hitler, Mao Zedong, and Idi Amin. The reasons are well-documented and easy to understand. It’s old-school political economy.

At this point in history, though, the opposite is also true: When the economy is way too big, the stresses and strains are too much for a liberal democracy to handle. Even in a huge economy laden with fat, the masses are restless and unhappy. They are susceptible to authoritarian personalities who seem similarly angry and bent on overturning “the system.”

That leaves the steady state economy, at an optimal level, as the greatest hope for maintaining the ideals of liberal democracy. Let’s start with the basics of optimality.

Optimality: Don’t Minimize It

The importance of optimality can be recognized by juxtaposing it with the other two options: maximizing and minimizing. Maximizing corn production on the farm, for example, might sound like a good goal, but it comes at the expense of other important conditions. To maintain soil health, preserve the aquifer, and even to maintain a reliable source of income, we’d want to optimize, not maximize, the level of corn production. We’d try to go light on tillage, fallow a field on occasion, and rotate crops, even if it meant a smaller harvest.

Similarly, our goal wouldn’t be to minimize many things, either. For example, it’s become popular to “minimize the use of fertilizer.” But the absolute minimum would be zero, and grain crops can hardly be grown on most farms without a boost of nitrogen. Conversely, too much fertilizer will upset the balance of nature in and around the field, negatively impacting the environment and ultimately the corn harvest itself. Again, optimizing is the proper objective.

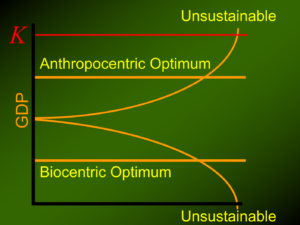

Determining optimum GDP in a democracy is an art, entailing the consideration of divergent viewpoints. Is there an optimum GDP for democracy itself? (Copyright — Center for the Advancement of the Steady State Economy)

When you stop to think about it, in virtually every scenario of economic activity, neither minimizing nor maximizing any input or output is prudent. Real, sustainable success is all about the optimum.

And in this case, at least, what’s good for the microeconomic goose is good for the macroeconomic gander. Just like fertilizer on the farm, the economy itself has an optimum level over long periods of time. That’s what the steady state economy is all about: stable or mildly fluctuating GDP at a sustainable level, for decades, and ideally at an optimum level. That means there is plenty of ecological capacity reserved for environmental challenges (drought, for example), balanced with a significant population of humans in a healthy, happy condition.

Achieving an optimal GDP is one of the greatest challenges for democracy in the 21st century. Merely estimating an optimal range of GDP is fraught with methodological challenges. But then, so are a lot of profoundly important policy goals, such as affordable health care, quality education, and homeland security. How do we know when we’ve achieved such lofty goals?

Not easily, and I am reminded of a profound, aging book—coincidentally focused on sustainability—called Muddling Toward Frugality. In a democracy, we muddle toward a lot of goals, striving for success, success that is sensed more than measured.

The argument here, though, is not only that there exists an optimum GDP for social wellbeing, an optimum we must muddle toward, plying such tools of democracy as government research, town-hall meetings, and public opinion polls. Rather, the main point here is that democracy itself has an optimum GDP, within countries and globally. If we’re not careful—if we get too far out of an optimal range—we might find ourselves with no democracy for muddling toward anything.

Trophic Origins of Democracy

It is no coincidence that the origins of democracy are attributed to ancient Greece, plus the “primitive democracy” of Mesopotamia. These are the same places where some of the earliest, reliable food surpluses allowed for a complex division of labor. As described with the trophic theory of money, it was agricultural surplus that gave rise to money as a means of exchange.

Greek agricultural surplus allowed Aristotle to philosophize; for example, about his preference for a democracy ruled by farmers. (Wikimedia)

But the use of money was far from the only social convention arising from agricultural surplus. The “demokratia” (power of the people) was another. Surplus allowed for the Mesopotamians and Greeks—just enough of them at least—to assemble and assess not only the status of grain supplies, but to plan water works, judge criminals, and discuss foreign affairs. It was a direct (not yet representative) form of democracy, including the practice of sortition.

Eventually a coherent political philosophy was put forth in Athens by the likes of Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. Just as importantly, agricultural technology and surplus evolved and spread through much of the world, freeing the hands for the division of labor, the exchanging of money, printing (and reading), and the development of democracy.

Over the centuries, democracy has undergone experiments and milestones: the Roman Republic, Indian sangha, Corts of Catalonia, Magna Carta, Polish Sejm, British Parliament, and American Constitution to name a few. Through trials and errors, democracy has evolved to become characterized by:

- Representative government

- Free and fair elections

- Multi-party system

- Separation of powers

- Rule of law

- Freedom of information

- Civil rights

None of these institutions is easy to maintain. They take due diligence, extensive coordination, and faithful adherence to a social contract between the governed and their government. They are costly in terms of time, money, and intellectual effort. They require the maintenance of substantial surplus at the trophic base of the economy.

Despite all the evolution and effort, democracy has remained notorious for inefficiency, instability, and susceptibility to mob rule. As Winston Churchill noted, “Indeed it has been said that democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.” It’s a nuanced quote, because Churchill was condemning “those other forms” more than criticizing democracy. But governance of any kind is a messy challenge, and democracy is no silver bullet.

Nor is it a bulletproof vest against authoritarian movements.

Democracy and Its Discontents

Today, roughly half of countries can be classified as democracies, although the precise number varies with the classification system. In 2019, the Pew Research Center classified 57 percent of nations as “democracies of some kind.” Another 28 percent exhibiting “elements of both democracy and autocracy.” In 2022 the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) classified only 43 percent of nations as democracies.

What most of these think tanks agree upon is that, globally, democracy is eroding. Of the 43 percent of nations categorized as democracies by the EIU, two-thirds were further categorized as “flawed democracies.” Freedom House reported in 2023 that “global freedom declined for the 17th consecutive year.” Larry Diamond at the Hoover Institution calls it the “Democratic Recession.”

Unemployment and inflation, in that order, are somewhat explanatory. Economic inequality gets its fair share of the blame, too. The International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (International IDEA) blames “pandemics, wars and climate change.” Some point to technology and the internet, especially the politically corrosive effects of social media. Others emphasize immigration and the cultural stressors that often come with it.

Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, one of a growing number of populist authoritarians. (Wikimedia)

As David Brooks wrote recently for the New York Times, “Like everybody, I’ve been trying to figure out why populism is having this broad resurgence.” “Broad” is the word! “Resurgence,” on the other hand, doesn’t provide the proper connotations.

The geopolitical breadth of populism suggests that, in addition to the conventional list of causes noted above, some deeper, fundamental force is afoot. In my opinion, this ubiquitous phenomenon is limits to growth, as manifested in environmental, social, and psychological strain. It’s “something new under the sun,” to borrow the unnerving phrase of the historian J.R. McNeill, who was referring to the environmental crises caused by two centuries of industrial economic growth.

Limits to growth are as broad as Planet Earth, but there is no “resurgence” of historic geopolitics. It’s not about the Marxist countries that long ago rejected capitalism so fervently as to succumb to central planning and communist rule. Nor is it about the obviously authoritarian Islamic states in the Middle East, Central Asia, and Africa. The “uptick in the number of authoritarian regimes” is something else altogether. It’s an uptick reported extensively in Europe and North America, but prevalent in many other parts of the world as well. It is something new under the political sun.

Limits to Growth, Complexity, and the Challenge to Governance

The breadth of democratic decline is because the world—nation states in the aggregate—is bumping up against limits to population and economic growth. Limits to growth is a complex of symptoms that includes global heating, ecosystem unravelling, and economic debt, among other crises. The limits are pushing desperate economic and climate refugees out of Catholic Latin America, Muslim North Africa, and Hindu South Asia alike. Homeland resources aren’t sufficient to support billions of occupants living in the Global South with reasonable levels of certainty, much less comfort.

But emigrants aren’t emanating only from the Global South. Russia and China are two of the top four emigrant countries. The UK and Germany are also in the top twenty. While most citizens in these countries are financially far better off than those of the “Global South,” they too find themselves getting more crowded, competing for fewer resources, and being exposed to the noise, crime, and general stress of a country in which GDP (and therefore the ecological footprint) either exceeds or is rapidly approaching the biological capacity. They’re seeking greener pastures. Not finding them, they’re starting to see red.

The basic principles of democracy are surrounded by nuance and difficult to maintain, especially at the limits to growth. (International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance)

But if limits to growth is such a common denominator of dissatisfaction, it is still fair to ask why the outcome is a democratic recession. Why don’t we see autocrats falling out of power instead? Why not turn toward democracy, “the most successful political idea of the 20th century”?

Autocrats have some key advantages in times of crisis. They can act quickly, unencumbered by the inefficiencies of bureaucracy. They operate free of the checks and balances of constitutional democracy. They can control the media and keep the public on their side. To the level that autocracy is achieved and maintained, it greatly simplifies governance.

Democracy, on the other hand, requires a great deal of information, education, organization, discussion, debate, negotiation, compromise, and synthesis before a policy direction can be settled upon, much less administered and enforced. It’s a complex endeavor. The political and bureaucratic complexity is like a collection of exorbitant transaction costs. It amounts to a crippling tax on government and society.

A society can take only so much complexity, and then it collapses, as Joseph Tainter has argued for decades. In other words, limits to growth apply to complexity, too. By extension, there are limits to the growth of democracy.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m not arguing for authoritarian rule. As a youngster, I pledged allegiance to the flag a thousand times. My Ph.D. dissertation was The Endangered Species Act, American Democracy, and an Omnibus Role for Public Policy. What was the “omnibus role for public policy?” Serving democracy (as laid out in Policy Design for Democracy.) And, as a civil servant in the American government, I was proud to serve the tax-paying public, ironically while autocratically gag-ordered.

Rather than denigrate democracy, I rail against the obsession with GDP growth that threatens democracy in two ways: the obvious way of breaching environmental capacity, and the overlooked way of complexity overload. As a long-time student of democracy—and ecological economics—I am convinced that the proper response to 21st century democratic erosion is steady statesmanship.

Some things depend so thoroughly upon a steady state economy that we can simply state, “[This or that] is a steady state economy.” For example, biodiversity conservation is a steady state economy. Peace is a steady state economy. I’m not sure we can go that far with democracy. The appreciation and maintenance of democracy is too complicated by historical, cultural, political, economic, and psychological variables.

One thing is certain, though: Democracy entails a steady state economy, within an optimal range.