The word “whiff” is used in baseball to describe when the batter swings and makes no contact with the pitched ball. The term presumably derives from the sound of hitting nothing but air.

This off-sequence post acts as a brief update that I wanted to present, without making a full-fledged blog post out of it (in hindsight, I may have failed). In the last two posts (here and here), I noted that recent rapid drops in child birth around the world could conceivably put us on track for an earlier population peak than previously anticipated—possibly as early as 2040 vs. the 2080–2090 timeframe.

That would be big news, and makes me continually ask myself: where is the disconnect? Is it possible that demography models are that wrong? I have discussed already (and will revisit in the next post) some of the potential blind spots for how this century develops. But here I look backwards to see if the recent drop in child births was itself a surprise to the demographers. If so, then it speaks to dynamics at play not captured in demography models, and that’s important.

I used the 2022 United Nations World Population Prospects (WPP) data (public) to build a list of countries that had the largest fractional declines in total fertility rate (TFR) from 2010 to 2019 (pre-COVID), and that also had projections in previous U.N. WPP products back to 2010. I show how (not) well the U.N. expectations match the actual story for these cases. I also throw in a few other countries of interest, including the three most populous ones.

The Top Drops

I will present six fast-decline countries in the order of greatest to least fractional drop in TFR from 2010 to 2019, before throwing on a few important population players. For each plot, the thick blue line reflects past data from the U.N.’s 2022 WPP effort. Dotted lines represent projections from WPP efforts in 2010, 2012, 2015, 2017, and 2019. Often the left edges are discernible to help sort them out. In each case, the latest 2022 projection (beginning 2021) is a blue dotted line, and fashioned (by the U.N.) to match up to the solid curve to avoid artificial disconnects. In some cases, I supplement with updated TFR reports from credible sources, shown as red circles.

Bhutan

Bhutan went from a TFR of 2.30 to 1.46 from 2010–2019, dropping to 63.6% of its 2010 value.

Bhutan has had a fairly steady track record, so that projections tended to be smooth extensions of the past curve. But the TFR recently dropped well below expectations, already well below where projections had it at 2040. The latest projection anticipates a modest “correction” to higher values that I can’t say I trust will materialize.

Timor-Leste

Timor-Leste went from a TFR of 4.85 to 3.34 from 2010–2019, dropping to 68.8% of its 2010 value.

This is an interesting case. Until 2019 (red dotted), the projections were very self-consistent. They did show a steep decline, but significantly delayed (by more than 20 years toward the end), and a little less steep. I surmise that data for this country was stale and incomplete, so that when better estimates became available, it was a bit of a surprise to see how quickly this country was dropping. That is: the model missed the dynamics that made for an early decline, and we again have a case of already beating previously-anticipated 2040 conditions.

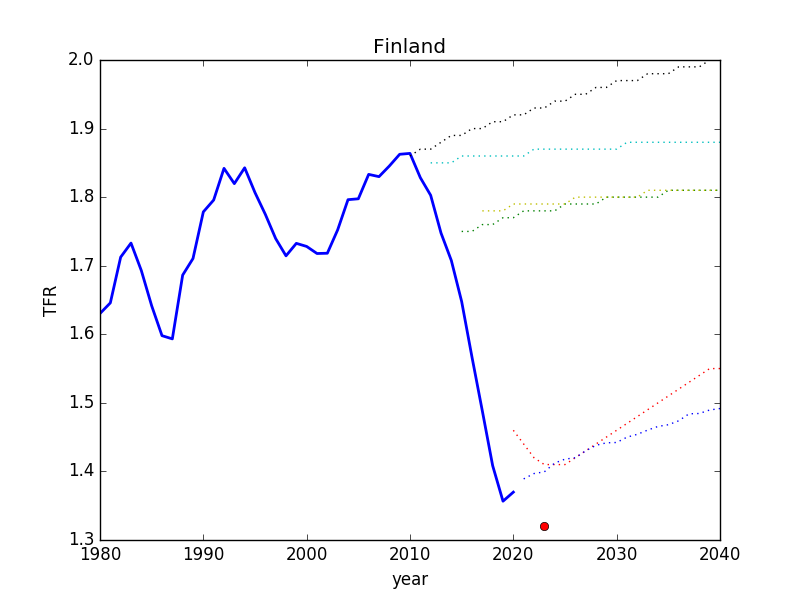

Finland

Finland went from a TFR of 1.86 to 1.36 from 2010–2019, dropping to 72.8% of its 2010 value.

The Finland case is a little hilarious to me. It’s a European country that presumably has high standards for tracking births, deaths, etc. Indeed, the projections always start out near the data, unlike the previous case, suggesting good up-to-date information. But the message from 2010 was: “Pull up! You’re too low!” In 2012, 2015, and 2017 the message was much the same: “You don’t really mean to do what you’re doing: just stop this nonsense and get back on the corrective track we think you should be on.” (My mock U.N. ends sentences in prepositions, apparently: another no-no). In 2019, there was some concession that maybe it could drop a bit more, but let’s not get carried away: it’ll come roaring back up, surely! Will it, though? Is it listening to the demographers? The last year on the blue solid curve shows a baby uptick, but Finland’s 2023 release (red symbol) puts it at 1.32, continuing to fall.

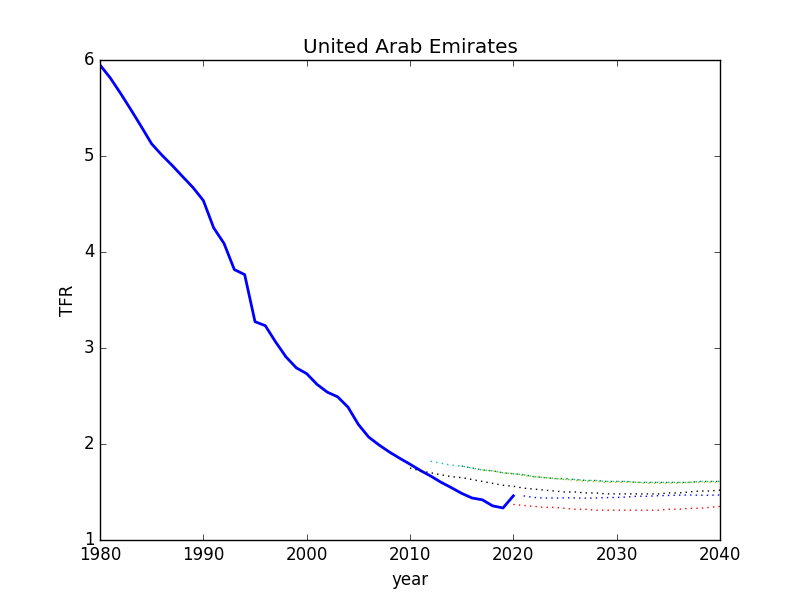

United Arab Emirates

The United Arab Emirates went from a TFR of 1.79 to 1.33 from 2010–2019, dropping to 74.5% of its 2010 value.

This one is a fairly business-as-usual extrapolation of a leveling curve. It did indeed drop below the earlier projections before ticking up again. Still, the latest data has it already below the 2040 projections from 2010 through 2017—well ahead of “schedule.”

Maldives

The Maldives went from a TFR of 2.32 to 1.74 from 2010–2019, dropping to 74.9% of its 2010 value.

No real beefs with this one. The 2010 projection appears to have missed an up-bump in a smooth continuation of older data, but subsequent models did a reasonably credible job of prediction, though systematically underestimating the rate of TFR decline (their favorite!).

Republic of Korea

South Korea went from a TFR of 1.22 to 0.91 from 2010–2019, dropping to 75.1% of its 2010 value. Pause to consider how low those are!

Okay: this one is pretty amusing to me as well. Korea has such a low TFR that it seems as if demographers simply don’t have a room in their imaginary house for such behavior to persist, and insist that fertility must execute a corrective rise any year now. “Pull up! Pull up!” But it just doesn’t. It has its own plans, and the gall to drop further against professional advisement. As was the case for Finland, it seems the 2019 model is the first to concede perhaps a smidge more decline before resuming a climb: a modicum of patience that was not respected. The latest data point indicates that the 2022 projection was another swing and a miss.

The Big Three

Now here are the three countries with the largest populations.

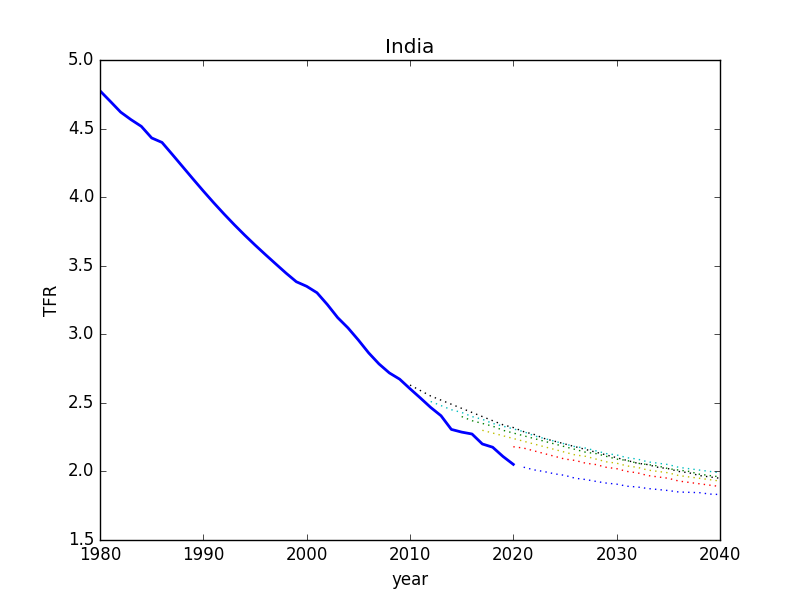

India

India went from a TFR of 2.60 to 2.11 from 2010–2019, dropping to 81% of its 2010 value. Importantly, it is now edging below replacement TFR.

India’s declining TFR has been a smooth no-drama affair: a modeler’s dream. Despite this, models have consistently underestimated the decline rates, always expecting a bit of a pulling-up. Again, it looks like a bias toward higher TFRs. Maybe the 2022 projection (blue-dotted) is okay, but the slope is discontinuous. Based on the history, would we really be surprised if the real trend undercut the projection?

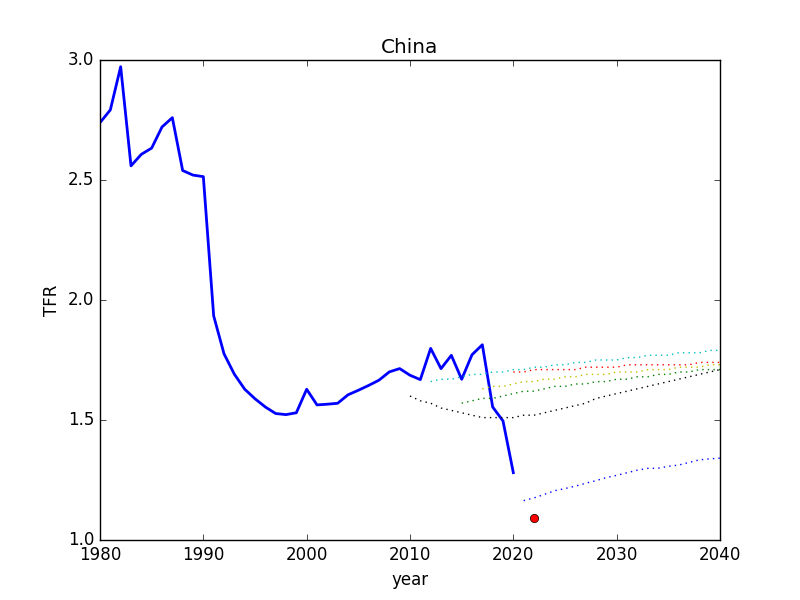

China

China went from a TFR of 1.69 to 1.50 from 2010–2019, dropping to 88.7% of its 2010 value.

Like South Korea, China’s TFR has been hanging out lower than the demographers think is reasonable, so that projections tended to anticipate a slow “recovery.” From 1995 to 2017 it looked like this was exactly the dynamic, but then a rapid decline commenced (pre-COVID). Oops. The last data point (red circle) indicates that the decline is still in progress—again ignoring the wishes of the projection’s trajectory.

A side comment here is that China imposed a one-child policy from 1979–2015 (exceptions were granted depending on location and gender). It looks like an effective crackdown happened in the early 1990s. Keep in mind that TFR is a “real time” metric unlike total population, which is subject to demographic inertia. Ironically, the country seemed to stubbornly saturate above 1.5 under the one-child policy until the rule was lifted, after which time the country “dutifully” headed toward 1.0 for real. It’s behaving like a cat!

United States of America

The United States went from a TFR of 1.93 to 1.69 from 2010–2019, dropping to 87.4% of its 2010 value.

This plot calls to mind the American flag: stars and stripes. Oh, say does that star-spangled banner yet wave… an expression of patriotism? Anyway, somewhat resembling the Finland drop, the U.S. has embarked on a rapid decline in TFR starting around 2008 (year of financial crisis…). The U.N. model, fully up to date on the stats kept saying: Nope. Nope. Nope. I’m not listening! Perhaps it was exciting in 2015 when the madness may have appeared to be over based on that little “shelf.” The next two trends launched from this shelf to execute an anticipated “recovery.”

Bonus: Italy

Okay, I threw in a bonus round, because I was curious to see another example of a low-TFR European country. This, then, is not part of an unbiased sample, but also does not represent a “cherry-picking” process: Italy was my first/only pick, and here it is:

The impression one gets is similar to what derived from previous examples: the U.N. model seems to be allergic to low TFR, desperate to get things “back to normal,” and whiffing on predicting downturns, to this day.

My Take-Away

I embarked on an unbiased exploration of the question: how well do the U.N. demographic models capture sharp declines in birth rates of late, and how are they performing on the most populous countries?

I can’t say that I was impressed. I expected the U.N. to anticipate at least some of the sharp declines, but in no case did they appear to “get out in front” of a decline, seeing it coming based on a deep understanding of underlying demographic drivers (that’s not how their modeling works: not systems-based—no room for unexpected emergent phenomena). This is especially true for low-TFR countries, where the model impulse to pull up seems to be rather strong.

My impression, then, is that the global rapid decline in TFR, as seen in regional aggregates prior to 2020, is not a feature understood by and captured in the models. It’s a new phenomenon whose (many) origins are not apparently represented in mainstream demographic models. In the end, something is making these trends go down beyond the model’s awareness, and that something is more likely to still be with us than to suddenly vanish. Perhaps the youth of the world are reacting in a “mature” fashion to the uncertainties of the future, and the justifiable sense that things are broken.

If the models are being surprised by recent developments across the world, then we should not be surprised if they whiff on the near future as well—not to mention the far-more-speculative late-century story. As I have dipped a toe into the world of demographers, I am truly impressed by the granularity and sophistication in their projections, but taken aback by what appears to be a faulty foundation of assumptions that render the exquisite attention to detail perhaps a bit misplaced—like perfectly arranged deck chairs on the Titanic. The world follows its own evolution, and will likely continue to thwart extrapolative projections based on a continued assumption of business as usual, dependent upon a context that is disappearing. I think this century is the one that breaks BAU in a big way.