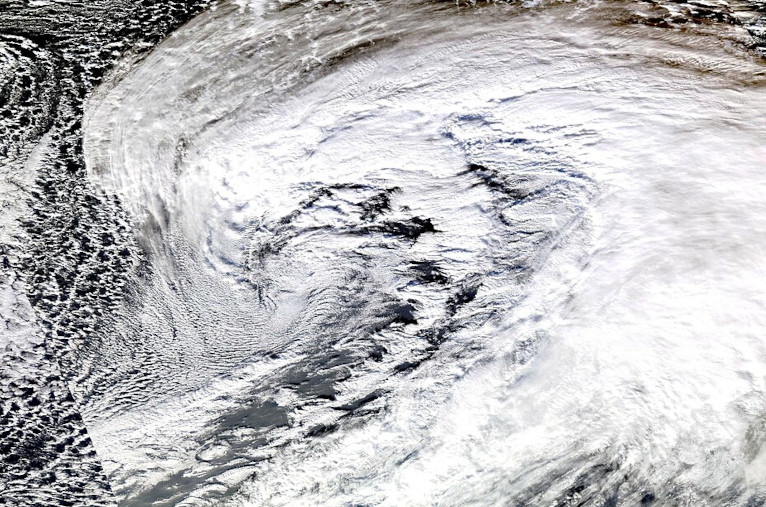

When Storm Isha hit Northern Ireland and northern Britain in January 2024, wind gusts of almost 100mph caused widespread damage to property. This strong extra-tropical cyclone also influenced both the insurance and energy sectors. Isha resulted in damages which required the insurance industry to pay out approximately €500 million (£427 million).

That’s a significant financial impact, yet considerably smaller than some previous extreme weather events, such as Storm Lothar which affected much larger regions of Europe with losses of nearly €10 billion.

Storm Isha also affected the energy sector. Fallen trees and high winds brought down power lines, so hundreds of thousands of homes lost power. Some energy traders benefited as the high wind speeds led to record-breaking wind power production and significant energy price drops. More than 70% of Britain’s electricity came from wind turbines at the peak of the storm, compared to an average of 30%.

Energy systems are being pushed to the brink by wind storms and heatwaves, compounded by gas shortages and price rises caused by the war in Ukraine.

Extreme weather events cause extensive economic damages, with more than US$100 billion (£80 billion) of this being covered by insurance in 2023. Understanding these extremes is, therefore, of great societal and economic interest. But the impacts of extreme weather vary depending on the industry. An event that benefits the energy sector can be detrimental to the insurance industry, and vice versa.

Climate change is likely to intensify these extreme weather events, potentially increasing or altering their impact on the energy and insurance sectors. With a greater frequency of heatwaves, pressure on energy systems will probably increase. Stronger storms could mean more damage and potentially higher premiums from the insurance industry. So it is essential that the meaning of extreme is understood in each context – this could help researchers like us, and society as a whole, to predict events and understand losses.

Focusing on the insurance sector, extreme weather events are of interest due to the potential to cause destruction and damages that need to be financially covered. Hurricanes and severe tropical cyclones are of greatest interest due to wind damage and flooding. From 2018 to 2022, these events caused economic losses of more than $450 billion, with just under half of this being insured. The costliest event in the past 50 years was Hurricane Katrina which devastated New Orleans in the US in 2005, resulting in approximately $100 billion insured losses.

The insurance industry classifies events with loss potential into primary and secondary hazards. Primary hazards, which include hurricanes, windstorms and earthquakes, have potential to cause the highest losses. Secondary hazards, such as wildfires or hail storms, occur more frequently and cause low to medium losses.

For primary hazards, such as European windstorms, it’s easy to assume that more events occurring causes higher insured losses. But only the strongest events are of interest, because these cause the most widespread damages. For example, the recent 2023-2024 winter season featured a very high number of storms in western Europe, but only one caused significant damage – from November 1 and 2 2023, Storm Ciarán hit France, Belgium, the Netherlands and the UK, resulting in approximately €2 billion in insured losses.

Despite the low impact on insurance, that winter season had a very high impact on the agricultural sector, due to extensive and persistent flooding that affected farmland and ruined crops.

Another factor to consider for insurers is the affected area and the economic exposure. Strong wind gusts and heavy precipitation from a hurricane over the Gulf of Mexico, or even sparsely populated parts of the US coastline, have little impact. But a hurricane impacting a built-up metropolitan area (as Hurricane Katrina did for New Orleans) will lead to huge damages and loss of life.

Insurance companies evaluating risks must account for a combination of the most extreme weather systems, and those affecting built-up, developed areas. The most risk-prone areas are quantified by examining historical events and assessing other possible scenarios that are generated by models. Risk experts also consider what impact historical events would have today. Increases in risk may be due to increases in population, density of the built environment, or GDP. For example, Hurricane Katrina’s impact would be $40 billion higher if it occurred today.

Many types of extreme weather, from dust storms to heavy snowfall, can have adverse impacts on energy infrastructure, generation and demand. Windstorms and flooding can damage power lines or the substations that distribute electricity to homes and businesses. In October 2023, Storm Babet left more than 100,000 people without power in northern England.

Extreme weather also influences the amount of renewable electricity being generated by wind, solar and hydropower. Wind droughts – low wind periods – are of particular concern. A prolonged wind drought from April to September 2021 affected the UK, Ireland and other parts of western Europe, with wind speeds almost 15% lower than average. This means that more gas has to be burned to produce enough electricity to meet demand. Researchers from the Met Office recently calculated that there is a one-in-40 chance of three consecutive weeks of low wind speeds (and low power generation) in any given winter.

Extreme weather affects energy demand. Temperature influences the amount of demand for heating and cooling, but wind speed and direction and rainfall also play a part. Southern European heatwaves are associated with a rise in energy demand of up to 10%, mostly due to air conditioning, according to researchers in Spain.

These impacts often overlap. Researchers from across Europe showed that wind droughts are particularly an issue if they coincide with extreme temperatures (which leads to high energy demand for heating or cooling). The impacts of extreme weather are further complicated by society’s move towards a more weather-dependent energy system and the changing distribution of extremes in a warming climate.

As our understanding of how extreme weather affects these two sectors develops, it is imperative that weather and climate information is tailored to professionals and researchers in each sector, so it can help to mitigate future damage and long term impacts.

![]() This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.