A new worldview is emerging, and it’s much richer, more meaningful, and more beautiful than the thinking that currently dominates our societies. I’m talking about planetarism, or what some also call planetarity.

“The concept of planetarity describes a new condition in which humans recognize not only that we are not above and apart from “nature,” but that we are only beginning to understand the complexities of our interdependencies with planetary systems.”

The Third Great Decentering by Nathan Gardels

Actually, it’s not only a new worldview that’s emerging. With it, or on top of its foundation, a new philosophy, identity, culture, science, and governance are forming. These things are still just emerging at the fringes of society, but they are emerging, and they are spreading.

While not fully or directly linked to a planetary worldview yet, the most urgent challenges of our time – such as climate breakdown, extreme weather events, wealth inequality, pandemics, and migration – are, due to their planetary nature, ultimately further fostering such a new planetary worldview, whether people like it or not.

“During the past several decades defined by globalization, nation-states and international organizations have focused on managing the worldwide flow of money, goods, people, services, and ideas. But many phenomena and flows that were once seen as mere background characters – such as microbes, atmospheric carbon compounds, oceanic plastics, the data flooding through algorithms, and more – have been revealed as central. Yet these non-human features do not care about our borders and political divisions.

We are entering a new era, in which our pressing challenges exceed the narrow concerns of human beings. These challenges call for a conceptual break with traditional human-centered understandings of the world and its politics, toward processes and institutions that are planetary in scale and scope.”

The Planetary by The Berggruen Institute

Of course, the big question is whether humanity will be able to cultivate planetary thinking and build appropriate planetary institutions before those challenges become too big to handle.

“We must work with the Earth, at all the scales of the Earth.

But to learn to work on planet-wide problems, we must become planetary thinkers. We must learn how to be humans aware of our natures, our Earthly context and the systems which make up the planet of which we are a part.”

What Does Planetary Thinking Mean by Alex Steffen

Let’s briefly look at a few categories within this new concept of the planetary:

Planetary Philosophy & Identity

“One indication that we may be approaching ‘peak Anthropocene’ is that philosophical quests across the world are coming to regard human-centric modernity as a fraught detour in the long course of life on planet Earth.”

The Philosophy of Co-Becoming by Nathan Gardels

I’ve written about this slightly before. Essentially, the separation or dualism ideology (i.e. humans ≠ nature and humans > nature) is losing its footing, and both how we perceive reality and, thereby, how we identify as humanity are changing.

A new way of attending to the world, a new way of seeing or experiencing reality, is slowly but steadily forming in certain circles. This new way of thinking is based on the idea of entanglement or of deep interdependence between not only our minds and our bodies but also ourselves and nature.

“[R]eality is neither undiscoverable, nor discoverable by the intellect alone, but by the whole embodied being, senses, feeling, intellect and imagination.’

Therefore, in order to find our home in the world, we need to approach the world as something to be embraced rather than manipulated.”

Understanding Ian McGilchrist’s Worldview by David McIlroy

“I think of the senses as a way of tapping my body and soul back into the Earth to renew myself; that then allows me to go on and do the work of right action and of hope, because I’m nourished by my family, by sensory connection. By “my family” I mean the wider family of the living Earth. I think that is a very important part of renewing our relationship to the Earth.”

Listening And The Crisis Of Inattention an interview with David G. Haskell

This changes not only how we see or approach the world but also how we see and approach ourselves. The Chinese philosophy of gongsheng which derives from the biological concept of symbiosis, explains this well:

“The notion of gongsheng […] behooves us to question the validity of the notion of an individual being as a self-contained and autonomous entity and reminds us of mutually embedding, co-existent and entangling planetary relations. It also inspires within us reverence and care toward creatures, plants and other co-inhabitants and even inorganic things in the natural surroundings.”

The Philosophy of Co-Becoming by Nathan Gardels

On top of that, human superiority thinking (as part of the separation ideology) is being rethought, further transforming our worldview as well as our own identity. In their new book Children of a Modest Star: Plantery Thinking For The Age of Crisis, Jonathan Blake and Nils Gilman talk about the third great decentering:

“If Copernicus’s heliocentrism represented the First Great Decentering, displacing the Earth from the center of the heavens, and Darwin’s theory of evolution by natural selection the Second Great Decentering, then the emergence of the concept of the Planetary represents the Third Great Decentering, and the one that hits closest to home, supplanting the figure of the human as the measure and master of all things.”

Just as Copernicus’ ideas changed our concept of “home” so does planetary thinking:

“We are part of a living planet. Note that I specifically don’t say ‘we live on a planet.’ To say we live on a planet is to imply the planet is a habitation; that we live on a planet the same way we live in a house, and may soon change addresses. This is not the case.”

What Does Planetary Thinking Mean by Alex Steffen

As these new planetary philosophies are profoundly transforming how we see the world and our role and place in it, new ways of approaching the aforementioned urgent challenges of this century are emerging.

“Climate change is a symptom of an inner crisis—a relationship crisis—which is intrinsically connected to other societal challenges such as social injustice and political conflict.”

What the Mind has to do with the Climate Crisis by Christine Wamsler

Planetary Culture

I’ve previously shared a study that shows that since the 1950s and the increasing use of technology & home entertainment, nature has continually lost its relevance or mention in music, art, novels, and movies. The conclusion:

“Artistic creations that help us connect with nature are crucial at a time like this, when nature seems to need our attention and care more than ever.”

How Modern Life Became Disconnected From Nature by Pelin Kesebir & Selin Kesebir

An interesting new trend that has emerged throughout the last few years within the literature industry is the genre of Nature Writing.

“Nature writing – in which the beauty of the natural world is used as way of exploring inner turmoil – has enjoyed something of a commercial and critical renaissance in recent years.

It’s not hard to see why. Our obsession with technology has started to feel more like a trap, making the the great outdoors seem like an appealing balm. Meanwhile the encroaching disaster of climate change is forcing us to reevaluate our relationship with nature, and maybe even stop taking it for granted.”

We’re Living Through A Golden Age Of Nature Writing by Olivia Ovenden

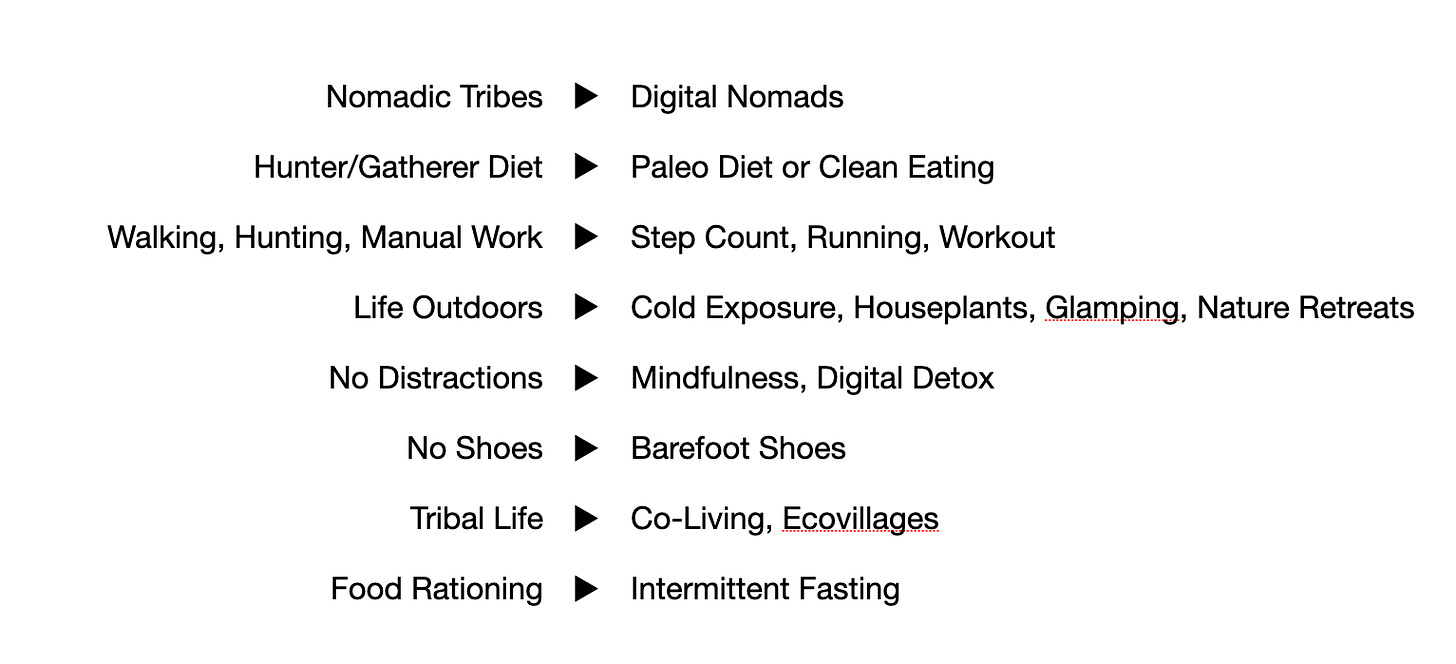

In other domains, we’re also seeing a significant push towards activities or lifestyles that promote a new relationship with nature and facilitate a sort of inner rewilding. We aren’t fully living again like our distant ancestors, who were more embedded in and in tune with nature, but we’re adding activities into our lives that mimic how these people lived.

I’ve also previously shared Erica Berry’s reflections on the deeper meaning behind “playing animal” social media trends, such as #ratgirlsummer, a hashtag shared more than 30 million times on TikTok:

“I think it’s worth considering what we are getting when we garb ourselves in the skin of the ‘rat’ or the ‘bear’, whether linguistically, virtually, or in costume. Not because these performances are accurate animal representations, but because the ways in which we make ourselves nonhuman have always reflected back our own yearnings and repulsions. We are as much running towards one cultural narrative – what the animal we are embodying ‘means’ – as we are running away from another: our sense of what the human ‘I’ means. […]

To perform the nonhuman is also to consider the ways we perform the human.”

An Animal Myself by Erica Berry

Another domain in which our relationship with reality, and thereby our relationship with nature, is increasingly being discussed is digital culture or digitalization as a whole. Society is entering a new reflection phase in which we are much more critically reviewing how technology (especially digital tech) has impacted us and the world around us during the last few decades.

It feels strange looking back at the outbursts of pure excitement that accompanied the introduction of the iPhone in 2007. Nowadays, in the 2020s, it seems like no matter how innovative a new technology or device is, a growing amount of people will always be slightly skeptical. Essentially, there are rising demands for a simpler, less hectic, and slower life as well as concrete calls (or plans) to restrict digital technologies for young people – such as China aiming to put a two-hour limit on children’s and teenager’s smartphone use, or UNESCO calling for a global ban on smartphones in schools.

“Nobody, I would argue, is having a great time at this moment and many (if not most) people are burnt out by the perpetual agitation that comes from the fear-mongering news cycle, by their feeds filled with posts they didn’t ask for, by the algorithmic interference and the nudging and the fact that nothing that they see on their screens can even be trusted. […] And this is before you throw A.I. into the works which is an amplifier and accelerator of fakery. […] This is just not sustainable.“

The End of the Extremely Online Era by Thomas J Bevan

We see yet again a similar picture in the realm of work culture. Recently emphasized by the progress in artificial intelligence, concerns are rising about the role of humanity and the nature of work. In the pursuit of hyper-productivity, work has been stripped of uniquely human traits such as beauty, joy, love, community, and dignity. The pandemic, with its introduction of essential (e.g. nurse) and non-essential (e.g. marketing professional) work categories and the shift to remote work (i.e. work without much water cooler talk and social serendipity), coupled with today’s hype about AI has made lots of jobs….well…extremely boring. Why?! In my opinion, this all comes down to work feeling increasingly machine-like.

Therefore, a massive need for a new, more humane, and more natural work culture is already growing. It’s no surprise (but actually quite ridiculous) then that work and productivity gurus like Tim Ferriss are now promoting stuff like Why You Should Stop Over-Optimizing, The Joys Of An Un-Optimized Life, and Slow Productivity (including the idea of a more natural work rhythm). The hustle culture is transforming into a soft life culture.

Planetary Science & Wisdom

In many ways, new scientific insights uncovered in recent years have driven many of the planetary culture and philosophy developments explained above. The big and obvious scientific fields here are, of course, climate science and ecology – weather doesn’t know borders or ideologies; the same goes for rivers and other natural ecosystems – as well as virology – viruses also don’t know borders. Planetary thinking is an important requirement for these domains of science.

Within biology at large, we’re increasingly learning the interconnectedness of things. We learn that cells have cognition as well, that the trauma of a grandmother can change the genes of its grandchildren, that our bodies live in symbiosis with the bacteria in our microbiome, that even the smallest or seemingly simplest animals, such as bumble bees, have emotions, and that plants might be able to see, just to name a few recent, mindblowing discoveries (or new theories).

“The concept [holobiont] has taken off within biology in the past 10 years, as we’ve discovered more and more plants and animals that are accompanied by a jostling menagerie of internal and external fellow-travellers. […]

You yourself are swarming with bacteria, archaea, protists and viruses, and might even be carrying larger organisms such as worms and fungi as well. So are you a holobiont, or are you just part of one? Are you a multispecies entity, made up of some human bits and some microbial bits – or are you just the human bits, with an admittedly fuzzy boundary between yourself and your tiny companions? The future direction of medical science could very well hinge on the answer.”

I, holobiont. Are you and your microbes a community or a single entity? by Derek J Skillings

We consequently see more and more evidence of nature’s positive impact on our mental and physical health as well as the massive importance of biodiversity for the resilience and health of ecosystems. The advice, for example, that you should get sun exposure early in the morning to improve your mood and sleep, which self-optimization gurus like Andrew Huberman give their followers, is basically just an outcome of such new planetary science.

In essence, an understanding of biology or nature (including our own) that’s based on a rather mechanistic blueprint – separate “cells”, “the heart as a pump”, “the brain as the central computing machine”, etc. – is increasingly being replaced by one that’s all about entanglement and interconnectedness. From system parts to relationships. From nouns to verbs.

“Once the microscope came along, it ushered in a worldview premised on individual identity. The first eyes to peer through those early eyepieces spotted what looked like empty boxes. English scientist Robert Hooke in 1665 coined them as “cells” because they reminded him of the small rooms where monks lived in monasteries. This formative moment led to a worldview called “cell-doctrine” — focusing on things — cells, this basic unit of life from which all living things are composed. Similar cells bundle to form tissues, which then cooperate to form organs, which then carry out the functions necessary to sustain the life of an organism, was how the thinking has gone.

We didn’t pay attention to all of the dynamic, fluid phenomenon, unseen and in between, which connects the organs to one another, and allows the whole system to communicate and stay in homeostasis.”

Just as the world of physics came to the very weird insights of quantum entanglement, other domains in science are increasingly seeing themselves entering a similar quantum entanglement era.

“Ecologists now perceive the trees in forests as connected to one another, trading information and nutrients across long distances, calibrating an ecosystem’s health. Mycelial networks are now part of conversations of people who, until recently, knew nothing about mushrooms.”

As I have previously written, I particularly find the field of traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) fascinating, or basically anything that brings new scientific discoveries together with indigenous knowledge. Because many indigenous cultures have known, not through science but through experience and ancestral knowledge transfer, a lot of the things that modern or Western science is now only discovering with regards to the interdependent nature of all things. This merging of experience- (slightly intuition- or spirituality-focused) and science-based (rationality-focused) knowledge is quite powerful and creates true wisdom, in my opinion.

One planetary scale example of this is the Gaia theory – i.e. that Earth is a giant living organism itself – which can be seen as a modern version of animism. Both animism and the Gaia theory have mostly received lots of ridicule from many scientists, but the idea of Earth as a vast interconnected living system has gained more acceptance in recent decades due to supportive, new scientific inquiry and insights:

“In the 1970s, chemist James Lovelock and microbiologist Lynn Margulis put forth a bold theory: The Earth is a giant living organism. […] Lovelock and Margulis called the idea “the Gaia Hypothesis” — named after the ancient Greek goddess of the Earth. It was openly mocked by many in mainstream Western science. “For many decades, the Gaia hypothesis was considered kind of this fringe sort of woo-woo idea,” Jabr says [Ferris Jabr is the author of the upcoming book Becoming Earth: How Our Planet Came to Life]. […]

Jabr found in the years since Gaia was first introduced, scientists have uncovered more connections between biology, ecology, and geology, which make the boundaries between these disciplines appear even more fuzzy. The Amazon rainforest essentially “summons” its own rain, as Jabr explains in his book. They learned how life is involved in the process that generated the continents. Life plays a role in regulating Earth’s temperature. They’ve learned that just about everywhere you look on Earth, you find life influencing the physical properties of our planet.

In reporting his book, Jabr comes to the conclusion that not only is the Earth indeed a living creature, but thinking about it in such a way might help inspire action in dealing with the climate crisis.”

Is the Earth itself a giant living creature? by Brian Resnick

Planetary Governance

“The planet is a political orphan. Theoretically, people have been designing global governance, but they still do so, naturally, in terms of nations. Think of the Himalayas. There are eight or nine rivers issuing from the Himalayas that service about eight or nine countries, from Pakistan to Vietnam, so the glaciers are important to these countries. But the glaciers are all nationalized. India owns India’s glaciers, Pakistan owns Pakistan’s glaciers, etc. The result is that the Himalayas have become the most militarized mountain range in the world.”

The Planet Is A Political Orphan with Dipesh Chakrabarty

Globalization has colonialism and hyper-extractive, inequality-perpetuating capitalism baked into it. It brings all humans on the planet together…in a hierarchical system. What would a better form of globalization look like? One that also includes non-human creatures and ecosystems? One that is based on planetary thinking?

“In contrast to concepts like “global,” “international,” and “transnational” — premised, as they are, on human perspectives and institutions — the concept of the Planetary does not privilege humans or any other particular species. Rather, it makes plain that Earth is not humanity’s alone. We share it with other living beings, nonliving matter, and forms of energy.”

Planetary Portal by The Berggruen Institute

Stefan Pedersen’s concept planetarism, similar to the Berggruen Institute’s idea of planetary, argues for a global entity based on the idea of post-nationalism instead of internationalism:

“What is a robust theoretical alternative to nationalism? For many seasoned cosmopolitan thinkers the answer is internationalism, which is generally perceived to be a sound foundation for creating a global polity in the form of a federation of nations. But this assumption is here criticised on the basis that it is founded on an inherent fallacy – internationalism is only a modification of nationalism, where the latter remains the ideological nucleus in conceptual terms […]. Because of the shared roots of nationalism and internationalism, the salient question is really; what comes after the international? The answer argued for here is; a novel paradigm of ‘planetarism’ that is not a compromise with the extant nationalisms.”

Planetarism: a paradigmatic alternative to internationalism by Stefan Pedersen

Or, for a different framing of Pedersen’s concept:

“The planetary “imaginary” of planetarism begins by thinking about how we can govern ourselves in a way that makes our feedback loops with the Earth sustainable for us and for the extant order of life on Earth, irrespective of national territories or sovereignties. […] Pedersen asks us to imagine a just and sustainable “planetary polity” to confront and unwork the unsustainable production of planetary space.”

“Planetarity,” “Planetarism,” and the Interpersonal by Jeremy Bendik-Keymer

The already mentioned Jonathan Blake and Nils Gilman add a bit more concreteness to these concepts by proposing a new form of governance and two exemplary, new institutions in their book Children of a Modest Star: Plantery Thinking For The Age of Crisis, which would all be based on a planetary worldview:

“In practical terms, they […] envision, as is already emerging, “translocal networks” of cities and regions for everything from resource-efficient joint procurement policies to close coordination of climate or public health goals, not unlike military alliances such as NATO that seek seamless compatibility of force integration across nations. […]

A illustrative cases, they call for a “Planetary Atmospheric Steward” (PAS) and a “Planetary Pandemics Agency” (PPA).

PAS would conjoin with and enhance the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s function of increasing knowledge of the climate, including by utilizing AI’s data processing capacity and fostering new monitory technologies and sensors, availing all national, regional and local levels of governance of the information they’ve gathered to stand behind its “authority to make and enforce decisions on limiting carbon emissions on the basis of what it knows.”

The authors make this controversial point clear: “The PAS would have the authority to set hard targets for net greenhouse gas emissions — not suggestions or aspirations, but enforceable rules. The PAS’s decisions on greenhouse gas emissions won’t be optional: they will have to be obeyed and implemented by governance institutions at all scales.”

The Third Great Decentering by Nathan Gardels

Some might now think that in today’s highly polarized and trust-deprived world, such ideas of post-nationalism and planetary governance are way too far-fetched. To those, I’d say that firstly, as explained above, the planetary identity, culture, and science are already emerging, and secondly, sometimes, the things that, at the outset, seem the most complex and challenging to transform turn out to be the things that transform the fastest. Maybe it’s the same with planetary governance because, as already mentioned, the most urgent challenges the world faces these days cannot be solved within national boundaries and nation-state- as well as human-centered thinking.

I think that we’re soon approaching a new phase in which band-aid solutions aren’t seen as adequate anymore by the greater public. Similar to new, innovative tech devices and software generating no more pure excitement but rather skepticism, politics won’t “excite” or resonate anymore if it isn’t radical (in the sense of truly transformative or impactful). And this relates to both ends of the political spectrum: even though the type of change demanded is very different, the nature of change demanded by both the right- and left-leaning voters is a radical one.

What the ‘highly polarized and trust-deprived’ public wants in an age full of global challenges might actually be most adequately satisfied with a new innovation in politics and democratic governance. Planetary governance that integrates direct and deliberative democracy ideas but also accountable meritocracy (i.e. nonpartisan technocrats who serve direct democracy) could be the next big opportunity within politics and solve both the trust crises and the inadequacy of nation-state thinking and acting when it comes to planetary-scale challenges.

A bit too abstract?! I previously shared A.J. Hudson’s idea of a People or Community COP “where community voices steer the conversations and commitments” as well as Corwin Schlump’s idea of a Carbon Central Bank, inspired by the design of central banks which are generally shielded from everyday politics and run mostly by experts:

“Likewise, an independent central carbon bank would shield climate change policy from the incentives of electoral politics, allowing its board of scientists to make decisions that would be beneficial in the long term, even if those decisions are unpopular with voters. One of the main problems with this is that the board would lack democratic accountability. This could be partially addressed by incorporating mini publics [i.e. deliberative democracy] into its structure: i.e., alongside appointed members, the board could include a random selection of members of the public, drawn from every segment of the population and part of the country. […]

If we are willing to delegate one of the most important economic decisions—setting interest rates—to technocrats in order to mitigate the effects of harmful short termism, it seems feasible to do this in the even more important arena of carbon emission reduction.”

The Case for Central Carbon Banks by Corwin Schlump

While the democracy part of the idea above is constrained by a country, in our planetary governance case, such mini publics could perhaps utilize the immense digital communication channels that we’ve created (i.e. the internet) and, therefore, also be established on a post-national or planetary scale, thereby include every segment of the planet or communities from a diverse set of planetary ecosystems (e.g. representatives from rainforest, desert, mountain, grassland, city, etc.).

I don’t know about you, but I get excited by these new concepts and ideas. Once we change our perspective and adjust our worldview and thinking to the interconnected planetary reality we’re living in, a massive new imagination space opens up. That’s where I find the hope that gets me through these uncertain and sometimes scary and upsetting times. ?

“There’s a massive difference between thinking of ourselves as living creatures that simply reside on a planet, that simply inhabit a planet, versus being a component of a much larger living entity. When we properly understand our role within the living Earth system, I think the moral urgency of the climate crisis really comes into focus.

All of a sudden it’s not just that, oh, the bad humans have harmed the environment and we need to do something about it. It’s that each of us is literally Earth animated, and we are one part of this much larger, living entity. It’s a realization that everything that we are all doing moment to moment, day to day, is affecting this larger living entity in some way.”