Sometimes things are simple and sometimes, they are complicated. In the Irish midlands, from 21-24th March, people representing dozens of organisations involved in agri-food came together, to work together, on how we feed ourselves.

Over these four days, there was detailed analysis of macro level EU policy regressions, and carefully curated listening spaces. Sometimes there was strategising, sometimes sharing. And always, spending time together to bake bread and build bridges. More happened than is outlined below, and more will come here on ARC2020 to give a flavour of the event. But for now, here are some thoughts – both simple and complicated!

A Brief History

Beginning in 2011, Feeding Ourselves started as a way for the Community farm in Cloughjordan to tell others in Ireland about this new idea – CSA, or Community Supported Agriculture.

Making local food resilience happen has always been a core element to Feeding Ourselves. But as the years unfolded, an ever widening set of people and organisations have gotten involved.

Talamh Beo, the Irish iteration of La Via Campesina and the Landworker’s Alliance, emerged from the event in 2017. ARC2020 brought a European dimension from 2018; by 2021, the Environmental Pillar, which is the advocacy organisation for 30+ environmental NGOs, added policy and ecological dimensions to the mix.

With each of these moves, what appeared from the outside to be an echo chamber widened into an expansive community choir.

Fast forward to now, and food poverty/access, health, rural and research dimensions are integrated too. As also is a way for conventional farmers – older and younger – to get involved. So how did it all unfold? Here’s some key takeaways from a participant involved from 2011 to today.

Community Action Works

Communities will have to do a lot of work themselves – and they are. People coming together know where they stand and know each other. Policy and politics sometimes let us down – as in the case of the Sustainable Food Systems Law, which, at a final hurdle, was dropped by a lily-livered EU Commission.

In Northern Ireland, there was a period with no government for three years until very recently. There is division and by the standards of the island, very industrialised farming, especially of poultry and pork, as we’ve covered.

And in the face of this, we saw examples of joyful, animated go getters just getting things done. One among these was the inspirational Carrick greengrocers. This community owned vegetable shop in Carrickfergus has been a hub and a hive since inception, being supported with real investment from the local community, working with local growers, exceeding expectations and pushing on with bringing people together around good healthy food. (Check a Feeding Ourselves reel over on Instagram)

We saw this too in the bigger picture examples from around Europe which were showcased. Both the Marburg Action Plan (via Henrik Maas and Ann-Marie Weber beaming in) and Plessé’s (via Thierry Lohr beaming in) multi stakeholder approach see communities come together in wide ways around making better food provisioning happen. (Marburg Action Plan)

This can mean retaining farms in your region, or providing via public canteens, or developing functioning food policy councils or making public procurement really happen where you are. It can mean, as Dr. Noreen Byrne of UCC’s Centre for Co-operative studies suggested, activating the ordinary – credit unions, the creamery co-ops, and more of what’s already there. It can be a theatre or a local football club, as fan-owned football club Bohemians in Dublin have done as an anchor institution, creatively defined, for the wellbeing economy in their part of Dublin. (being featured globally for it too, as here in the New York Times in March 2024)

Communities must come together – as in Plessé, as in Marburg, as in Carrickfergus and Cloughjordan – seize the initiative, and show policy makers how it’s done.

In other words, we must build a sustainable food system ourselves because we can’t wait for a faltering, fractious, Farm to Fork process to help us out at EU level.

Think geographically

When thinking not just of problems but also of solutions, what emerged was working on a landscape and water catchment level. The carrying capacities of the land and the needs of the people in places could mean, for example, that nitrogen budgets in demarcated places make sense.

Clearly, there is too much nitrogen in the wrong places, and a decline in mixed farming which can be a way to be more efficient with it. We heard about the problems with nitrogen from Elaine McGoff and Paul Price, and we started to develop approaches that might help ameliorate them. (see Paul’s Oireachtas submission on emissions here – 2022-03-24 Paul Price); See Elaine’s 2024 submission to the Oireachtas here)

Brian Meredith (Talamh Beo) shared a panel with Paul, and he spoke of the challenges and opportunities of moving into mixed farming, whereby he now grows crops on the Laois farm for the first time in decades.

More broadly, a nitrogen budget, within water catchments, would be one of the ways we could be fair to both people and the environment. Some individual farms could potentially be allocated more N than they currently are, others less, but we could be more consciously distributing this precious resource.

Look Geographically too – the case for land observatories

Land Observatories could help with the landscape level approach, and take into account more needs again. We saw excellent examples from Plessé in particular, and the SAFER approach from France came up more than once. Ireland indeed had a land commission for most of its time as an independent state.

In Plessé, where a very participatory approach to needs and resources, with an emphasis on protecting farm numbers while integrating societal wider needs, has seen the number of farmers increase rather than decrease. What’s more, the transition to agroecology continues apace.

With land consolidation rapidly becoming a problem in Ireland now too – as it has been for years in Europe – there is an urgency to this. Farm land is being sold for tens of thousands of Euros an acre in Ireland, with purchasers potentially thinking of all kinds of things other than producing food.

The needs and benefits of a more French style SAFER approach is emerging as common ground and a unifying factor between a lot of divergent farming and food interests (Read the Scottish government assessment of SAFER, courtesy of Daniel Long dairy farmer and Tipperary PPN chair – Safer Scottish report)

Solidarity times

Ruth Hegarty and Cynthia Masina looking on at Donegal Food Response Network’s work on improving food banks

We are in a time of something like disaster capitalism, with a bonfire of environmental regulations occurring. The far-right is trying to seize the moment, putting themselves forward as representatives despite being rejected by so many farmers and their organisations. This is cover for exclusionary regression on women, migrant and LGBT+ rights – it needs to be resisted at all levels.

The agri-food system implicates everyone. Wider considerations too, such as diet in direct provision featured at Feeding Ourselves. With set meals and times, and no options to cook or ask, people in the international applicant system are often othered.

Cynthia Masina eloquently represented this reality, reminding us that people have needs and desires in here too. As a simple example, what of people with diabetics with rigidly set meals? What of the dignity of cooking and learning how to cook?

Food banks have grown in Ireland, especially up north. How do we ensure food access, food dignity, and maintaining prices for farmers and ecological standards in this growing, emerging context?

In a way, the success of the Food Cloud approach to food waste – which featured at a Feeding Ourselves in earlier iterations – has moved fighting food waste into a cost saving, good publicity opportunity for supermarkets, while doing nothing to address below cost selling and other power issues in the middle, between producers and eaters.

We heard from inspirational folks like Joanne Butler in Donegal and the Open Food Network in the UK, who are pioneering progressive ways to bring more holistic thinking and acting into food access.

Joanne Donegal established Donegal Food Response Networks, to improve many aspects of the burgeoning number of food banks popping up around the north western county (current count 17). “I noticed there was lack of nutritious food and amount of sugar in food bags given out to families was huge ” the Donegal woman said.

She started a conversation with Food Cloud, and now has introduced a grower’s project, which brings tonnes of locally grown vegetables into the system. Plastic packaging has been reduced, and, after an eight week pilot, 60 tonnes of local veg distributed.

And the Talamh Beo Local Food Policy Framework is about solidarity too. Each day, further work was done to flesh out what’s in it and to build a campaign of momentum to make it real. At both ends – producers and eaters – institutional and financial supports could be put in place to embed local food access as part of building community resilience.

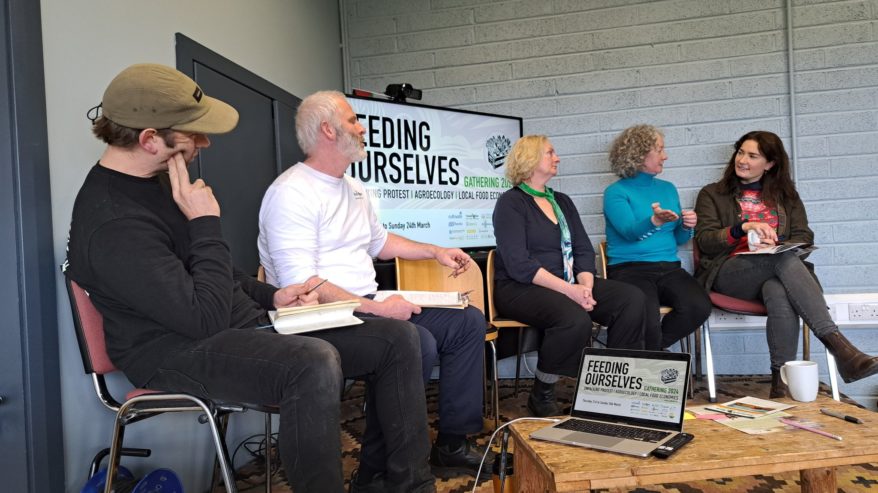

Everyone at the table

Ray o Foghlu; Thomas O Connor; Ailbhe Gerrard; Oonagh Duggan, Hannah Quinn Mulligan (L to R)

There’s genuine inclusion, there’s everyone with a real stake being at the table, and there are fake processes which function to provide cover for business as usual. It now appears that a charade of dialogue has taken place at CAP and wider EU levels, where NGO goodwill, time and expertise is hoovered up for years, but where legislation can get rolled back at the first signs of anything getting in any way tough.

A facade of stakeholder dialogue that was announced recently at EU level in these troubled times. Here, groups were hand-selected to talk. Concurrently another process was underway anyway, with a week of ad hoc meetings with farmer organisations and a series of militant confrontational protests which forced regression on environmental regulations.

And yet even here, many farmers were not asking for these changes. Farmers want dignity and livelihoods, to have some certainty and a fair playing field. Indeed only COPA of the farm four organisations expressly asked for green rule regression: CEJA, ECVC and IFOAM EU did not. These latter, though smaller, represent youth and agroecology. They are the future.

How do we connect meaningfully, when so much of what happens at the macro level is subterfuge and sabotage? One way is to try to build real bridges. Bridge-building had its own dedicated session at Feeding Ourselves, but it was present everywhere really.

That dedicated session saw a range of people, each of whom made efforts to reach out to others, talk a little about what they did and how they did it.

- Ailbhe Gerrard teaches in agricultural collage and farms organically by a nearby lake – the Tipperary woman organises Field Exchange, which uses a variety of methods to help farmers encounter diversity in action.

- Oonagh Duggan is perhaps the most farming-engaged of environmental advocates, visiting so many farms and events with an open-mind and eagerness to engage.

- Ray o Foughlu an online communicator between factions if ever there was one, has made regenerating native trees along river corridors attractive to farmers when forestry on farms has regressed so much of late.

- Thomas O Connor has an amazing mixed organic farm, equally impressive good food store, while working tirelessly for Transition Kerry and Talamh Beo among other activities.

- Moderator Hannah Quinn Mulligan, known to many as an agri-journalist, is also a recent convert to organic with her dairy farm while now also direct selling her milk to the Urban co-op in Limerick.

While Feeding Ourselves casts a wider net now than it did previously, there are other process at the national level that do similarly. One is the NESC process – NESC being the National Economic and Social Council, which gives advice to government in Ireland on strategic policy issues.

Niamh Garvey told of how NESC brought together a range of stakeholders on just transition in land use and agriculture for an 18 month process recently (including this author as a representative of the Environmental Pillar).

The aim was to explore how to achieve targets in a way that is socially inclusive, economically viable and environmentally sustainable. It was not about the environmental targets per se.

Process was as important as outcome, and farmer engagement was key to this, with regional meetings around Ireland. Farmers colour-coded interventions (e.g. biogas, afforestation, extended grazing) which were then categorised by difficulty levels.

Sometimes the most difficult thing was the most impactful from a climate perspective – e.g. rewetting – so ‘hard to do’ meant that more work would be needed to make the thing a reality. This might mean more supports and established, longer term payments would be needed compared to the low hanging fruit which might be easier to initiate. Rewetting, after all, could give a much bigger bang-for-the-buck than many more meagre but easy actions.

20 recommendations were put forward, in the areas of action/ambition; inclusion, opportunities and fairness. (see table 2.1 on page 8 here in NESC report 162)

The final report was agreed by farming organisations, the environmental pillar, trade union representatives, employer group representatives, the community and voluntary pillar and government departments. This is not typical for how these things can transpire in Ireland.

Two strongly emergent elements were the real effort needed to scale up and align advisory services, and the importance of deep listening and a genuinely inclusive process.

As it happens, these emerged as two strong themes for Feeding Ourselves this year too.

Developing skills for transition

Farm walk for the Codecs Horizon Project delivered by Torban Marl of Cloughjordan Community farm on the Sunday of feeding Ourselves

Agricultural Knowledge and Innovation Systems (AKIS) in Ireland is dominated by Teagasc – the Department of Agriculture’s research wing. And it doesn’t appear up to the task, in a transition context.

Teagasc is set up for an era defined by fertilizer and fossil fuels, in a post-colonial context defined by large-scale commodity exports.

There is little to help develop local resilience and short supply chains from these quarters. Into this vacuum informal, often peer-to-peer supports have emerged, and other ways to help develop diverse and resilient agri-food systems. NOTS The national organic training Skillsnet) is chief amongst these, but the room was filled with people contributing in their own ways to this too.

One of the most energetic and dynamic elements of Feeding Ourselves was the EU4Advice mapping excessive of what there is of an agroecological AKIS in Ireland.

Led by the Grounded/Amped/Operation Food Freedom Crew from Utrecht in the Netherlands, who work in regenerative resilience, a gloriously messy and interconnected mindmap emerged – and continues to emerge. This is a solid foundation to work from, and much needs to be done.

Real dialogue means really listening

Deep Listening Session

Deep Listening Session

Real proper deep dialogue is important. It can be both cathartic and nourishing to know you are being listened to. An approach developed initially last year at Feeding Ourselves is a closed deep listening session between regional conventional farmers and the rest of the event attendees – agroecologists and environmentalists.

A real dialogue starts with deep listening – with really getting to better understand the other’s starting point. It isn’t about point scoring or responding with advice for others. It’s about taking the time to develop empathy, then compassion. It’s about having the space to really go into how you – you – really feel about things.

So, on the Sunday morning after the movement building, the eating and the dancing of the night before, after the days of talking and thinking and strategising, a wide selection of farmers older and younger from the region were personally invited to spend time with us.

We wanted farmers to tell us how they felt about their farming and the context they are in. There was also, this year, an opportunity for two way listening. This made it an altogether more worthwhile experience.

People were encouraged to really speak from the heart, to let others know how they feel about different aspects of their farming experience. Others were encouraged to be honest about how they felt about aspects of farming, or their sphere of related work on environmental policy.

Those who attended were very positive about the experience, finding it to be very worthwhile, and in many cases quite new. This private, respectful space was one where people were safe to speak about how they really felt, about any aspect of the wider or narrower farming domain.

In these times of ever more polarisation, it’s good to get to know each other, one person at a time.

Feeding ourselves is a lot of things – it’s a network, it’s an event, it’s movement building – and it’s growing. First with CSAs, then agroecologists, then local food proponents, then those with wider food justice concerns, then environmentalists and ruralists, and now also conventional farmers from the region – in all their way, with their own diversities.

Maybe we’ll see you here next time.