Where the Desire to Write Comes From

In the 1990’s I spent years as an actor, director or academic bringing short productions of Shakespeare scenes to rural high schools. Audiences were welcoming and our small companies often lingered after shows to talk with students about their lives. During these conversations I began to hear disturbing stories and to see unexpected things: opening a phone book to get to know Williamsburg a little and seeing a bull’s eye printed on top of the city map with evacuation directions in the event of a nuclear attack, warnings by high schoolers in eastern Idaho not to drink the tap water because it was contaminated with nuclear pollution, listening to kids in eastern Idaho describe how their parents were getting sick and their cattle dying from local water polluted by nearby munitions testing sites, and hearing from northern Michigan locals about the countless barrels of toxic waste they claimed had been deposited by the military into Lake Superior. After enough tales, I decided to take early retirement from my academic career and work on environmental issues as best I could in my home state of Illinois.

And Then…

On February 13, 2024 I learned that I have a rare cancer called AML, or Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Only 1% of the cancers diagnosed in the US each year, a little over 20,000, are AML and a large percentage of them begin after a person has had multiple courses of chemotherapy, which I have not experienced. The majority of them occur in elderly patients.

A significant number of AML cases are now recognized to stem from environmental toxins; benzene and ionizing radiation are common causes, but “forever chemicals” (PFOA, and more), fertilizers and small airborne particulate pollution found in both urban and industrial agricultural locations can cause AML too.

This information has me wondering how a 67 year old woman who has lived most of her life trying to eat a healthy diet and exercise somehow managed to expose herself to toxins that cause AML. Admittedly, one of the other risk factors for AML is cigarette smoking, but I smoked in my 20’s and kicked the habit decades ago.

The diagnosis has me wondering about other questions too, larger questions about what my Baby Boomer generation accepted for many years as necessary parts of our environment and culture without really considering the costs to us of that acceptance.

And finally I need to consider that AML is a very fast moving disease. The oncologist suggested I may have as little as three to five months on this planet, and not all of that time may include days when I can sit at the computer and type words into this window.

AML Cases and Benzene Exposures – From the Personal to a Much Larger Cultural Story

As I began to explore chemicals linked to cases of AML, I decided to start with benzene. Multiple articles about AML and this environmental exposure came up in my searches. Benzene exposure is part of both agricultural and urban areas, and I have lived in both of these during my lifetime. I had a vague sense that benzene was used in tire manufacturing, but really knew next to nothing about the chemical. And then I found, “Benzene, the need for a new global Industrial Revolution and the big challenges that lie ahead.”. For example, from the author I learned:

“Everyone needs to understand that modern-day life would be impossible without benzene, as with the other petrochemicals.”

This statement comes from an author writing for the Independent Commodity Intelligence Services. He is writing for CEOs and top managers of companies that are dependent on benzene. He is warning that if fossil fuel production and fossil fuel refinement are significantly reduced, the benzene supply needed for “downstream” production of chemicals such as other carcinogens toluene and MX, the ready supply of benzene will also be greatly reduced, thereby making industrial business as usual impossible.

For an industrialist convinced that the way manufacturing currently happens is the only and best way that it can occur, this news would be alarming.

The author, John Richardson, acknowledges that since benzene’s cancerous effects have been recognized, its manufacture and use–especially as a fuel additive–have been significantly reduced. The question remains, though: how much benzene is currently being used? Richardson is happy to provide both data and projections. From 2001 to 2021 the “developed world” consumed a little more than 500 million tons of the stuff. That level of use is expected to stay largely the same from 2022 through 2040. However, the “developing world” is another story. From 2001-2021 the developing world consumed about 300 million tons of benzene. The bad news comes from estimates of what they will use from 2022-2040. In efforts to bring people in the developing world the “lifestyles” similar to those enjoyed in developed countries, the developing world is projected to use over 750 million tons of benzene. In other words, on a planetary scale, benzene use is expected to increase in a big way.

Implicit in Richardson’s article is the warning that industrialists need to push to keep fossil fuel production and petrochemical processing a healthy part of the industrial world. And as I realized that was his message, I began to understand why benzene and a host of other petrochemicals continue to be with us, in spite of the harm way too many people understand these chemicals can cause. Efforts to address climate change and efforts to reduce the incidences of environmental cancers need to be understood as linked. My mind began to imagine ways that I might make connections between the very private reality of a cancer diagnosis and the surrounding environment that gives rise to so many of them. Research soon revealed to me that physicians and scientists have been studying this connection for decades.

According to author Richard W. Clapp, benzene is one of the chemicals linked to AML. According to Clapp, benzene has been a known carcinogen since the 1920’s. He describes how our government has decreased the amount of benzene that a person can safely be exposed to, and ends by writing that it is now generally recognized that there is no safe level for exposure to this chemical.

The article examines a number of chemicals associated with cancer diagnoses, but for me the most interesting part of what he wrote came at the end. In his final paragraphs, Clapp pointedly asks, with so much information known for decades about the carcinogenic dangers of over 100 chemicals, why are the chemicals still so frequently a part of manufacturing. He reaches the same conclusion as I did after reading Richardson, but let him speak for himself.

In a section titled “Failing to Act on What We Know,” Richardson contends that

“we as a society have repeatedly failed to act on this body of evidence to reduce and/or eliminate exposure to carcinogens wherever possible. Although we have made significant headway on preventing disease associated with exposure to lifestyle factors such as tobacco smoke, we have ignored the dozens of environmental and occupational agents that contribute to new cases of cancer each year.”

He goes on to describe how economic and political factors keep these dangerous chemicals in the environment, including the profit motives connected with cancer drugs. As companies increasingly move to create highly targeted cancer treatments, the cost to patients skyrockets. Studies are now tracking who receives these new drugs based not only on health and age factors, but on income levels as well. Not surprisingly, those with more yearly income are choosing these treatments more often than those with limited incomes. I encountered a stark example of this reality when trying to understand some of the novel drugs now being promoted for AML treatment.

In a press release from Syndax Pharmaceuticals, 2023, not only were their drugs revumenib and axatilimab’s trials described, but the company’s increasingly promising financial situation was outlined. Syndax specializes in creating narrowly targeted cancer drugs, including those for AML. The company’s stock is traded on the NASDAQ stock exchange. This company must turn a profit in order to stay in business. Luckily for the company, Syndax issued over 12,000,000 shares of stock in the 4th quarter of 2023 and has already sold almost 3,000,000 shares, allowing it to estimate it has an income stream sufficient to continue its work through 2026.

Returning to the Personal for a Bit

At the moment I am sitting in a recliner, my laptop balanced on a quilt between my knees, as I attempt to craft this complicated article. I’m relatively pain free–mostly body aches that I can knock back with some Tylenol. My mind is relatively clear, my energy level is much less than what I knew before my diagnosis, but I am functioning for now. There’s the bother of a secondary urinary infection, one of the dangers of AML, that is being treated with a round of antibiotics. And I’m still enjoying the quality of life benefits of a blood transfusion that improves oxygen levels for me, and a number of other benefits in my circulatory system.

What would you do if you learned at 67 that you had this disease? I’m told that without treatment I can expect 2, 3 or up to 5 months of life, that I will simply grow weaker, that I may die relatively suddenly from a stroke, heart problem, or acute secondary infection, but failing those I will likely experience little pain and may have quite a few weeks with my husband and son, living at home, and gently participating in the last spring I will know in my garden.

The alternatives I have been given by an oncologist seem a bit like choosing to go to Las Vegas–gambles all of them with the odds being that I will not see much of an increase in time in this incarnation and will be required to spend weeks of it in hospital dealing with the pain of cancer treatments with, as my doctor admitted, no guarantee that treatment will improve my life expectancy. Those weeks in the hospital will also mean greatly reduced time with my family and garden, and when I return from hospital, the remaining weeks I have at home I will spend in a greatly weakened condition.

I have chosen to have monthly blood transfusions for as long as they are permitted, and when they are no longer available, to enter home hospice care. What I have chosen is selected, especially by women, more often than you might think. Perhaps we choose this approach for financial reasons, perhaps we choose it for the family reasons that I have–more quality time with loved ones. But it is a choice–my choice–and my family agrees with it. How do you measure what is better: a short number of months largely functioning as I am now with the ones I love around me every day, or an extra two or 10 months often in the hospital and in pain?

The other task I can attend to with the choice I’ve made is to write, which brings me back to the next aspect of the tale I am trying to share–how our legal system contributes to the ability of chemical manufacturers to evade responsibility for the poisons they visit upon us all.

The Difficulty of Ascribing Responsibility for an Environmental Disease–Especially in the US

In Europe environmental oversight organizations employ a concept called the Precautionary Principle. Rather than demanding that a direct causal link be established between, for example, chemical exposures and cancer, Europe studies the chemical by focusing on peer reviewed studies that are not conducted by chemical companies. If the studies offer enough concerning data, even if an incontrovertible link cannot be established between a chemical and a particular cancer, the European organizations may issue a statement saying the chemical is a probable carcinogen, or it may ban the chemical from use in Europe entirely, because banning the chemical until it is proven safe is the prudent choice to make.

In the US, the process of determining the dangers of a chemical is hampered by a number of factors. For years the US has been underfunding the Environmental Protection Agency and the Food and Drug Administration, along with many other oversight departments. The underfunding has led to the closure of governmental testing labs. Their closures have forced the government to increasingly rely on industrial labs for testing and interpretation of testing results. Corporate labs have a vested interest in proving that what they are manufacturing is safe. They also insist on a standard, especially in court cases, that requires someone claiming to have a disease caused by a particular chemical to prove that no other chemicals are involved. The possibility that multiple chemical exposures may have contributed to a disease becomes a boon to companies who rely on the current state of scientific methodology. Though scientists continue to develop techniques that will allow them to understand the links between pollution exposures, genetic mutations and the timing of these factors, they lack techniques that will allow them to determine what percentage of a chemical exposure has led to disease when a person has had multiple exposures to chemicals. For example, a chemical company may claim its pesticide is not responsible for a person’s disease by pointing out that the claimant was a cigarette smoker, a combination of factors that has allowed some chemical companies to have cases against them dismissed.

So far I seem to be suggesting that all ultimate responsibility for environmental cancers should be attributed to chemical manufacturers who recklessly introduce these substances into the environment in the pursuit of profit. That contention, though, is only part of the truth. Other factors related to environmental cancers like AML have to do with time, with the nature of a particular cancer, and with choices individuals make about where to live and what chemicals they willingly bring into their homes. For example, if you are a spy and someone decides to give you plutonium in a cup of water, that event will be enough for you to experience fatal heavy metal poison. However, prostate cancer develops after approximately 9 factors have been put into play. Other cancers will involve a series of genetic mutations finally sufficient for the run-away train that is cancer cell development to really fly. And the amount of time that these cancer causing events can take varies from a few days to years or decades.The time factor is also important because people make personal choices during these periods, choices that when first made seem completely innocuous. Let me give you some examples.

My father was a carpenter. Our family often chose to buy older homes, and to improve them while we were living in them until they had been remodeled to our liking. It is likely that we kids were exposed to lead paint, silica dust, asbestos and more as we lived in these works-in-progress. All the tradesmen we knew were doing the same thing with older houses. It was a way for skilled artisans to end up living in much nicer homes than they could ever afford to buy. After I married, my husband and I also bought older homes and worked on them. The original home builders had used materials that they did not understand were dangerous and we did not always take sufficient care to limit our exposures to materials within them.

Here is another exposure over which we had no control. As a kid I lived in Chicago at a time when air pollution was so bad that particulates and chemicals built up in the skies over the city from Monday through Friday, only to have weekend rains wash all those pollutants down to the ground on Saturday and Sunday. These cycles of air toxin buildup followed by weekend rains that washed the pollution onto our front lawns continued for years. These pollutants included those from Chicago vehicles. Leaded gasoline’s last phase-out in the US didn’t happen until 1996, and I lived in Chicago in the 1960’s.

When I think about the homes my husband and I have owned in the last twenty years, one was over a hundred years old and we remodeled it extensively, one was located blocks from a metal reprocessing facility, one seemed to sit beside a huge green space that I learned after purchasing the house was actually a superfund site, and one, where we now live, sits less than a mile east of a huge EV vehicle manufacturing site and a little more than a mile west of a tire manufacturing plant. I’ve also lived almost thirty years in an industrial agricultural area with air borne particulate pollution, as well as pesticide and fertilizer applications that are applied every fall and spring. The truth is that it is growing increasingly difficult to find US communities that do not lie near polluting industrial or agriculture areas. It has also been true for a very long time that the majority of people in the US lack the financial resources to relocate to safer communities, even if they were willing to do so.

Popular cafe close to tire manufacturing plant near to where author has lived. Photo credit: Samuel Galewsky.

In my 67 years, I have exposed myself to chemicals and carcinogenic substances of countless kinds. There is no way for me to be sure what exposures have brought AML into my life. And while I am most unhappy to think that chemists should have understood just how dangerous were the substances they were inventing and promoting as products, I bear some responsibility for the choices I have made that may have contributed to illnesses I have experienced over the years.

This complex, shared responsibility for what has developed in our country includes issues of trust in what manufacturers tell us is safe, our own economic or time limitations, the preferences we develop for certain products even after reports come out that what we have been using is not safe, pressure from our communities to turn a blind eye to companies that are polluting air, water and land because they also provide a significant number of jobs, and our tendency to trust official messages from government and industry because we do not completely understand how larger economic factors cause leaders to post less than accurate messages in order to keep current systems in place.

So who exactly is to blame for the highly polluted state of the US? The manufacturers? The underfunded government oversight departments? The economic and political leaders who fear the negative consequences that will result if more stringent safety measures are put into practice? Ordinary people with bad backs who choose to trust that herbicides are safe because they do not have the strength to manually remove weeds from their yards? Others who are more afraid of the disease carrying roaches in their apartments than they are of the pesticides sprayed within their apartments in order to keep them insect free? Is determining the greatest responsibility for the environmental cancers now plaguing US residents the only way for us to attempt to improve the environmental situation in the US?

The preceding questions return me to the EU’s Precautionary Principle. The EU pulls dangerous chemicals out of the environment, sometimes before they have a chance to do harm. The chemicals are banned before they are released to markets. The European systems are not without difficulties, as there are many European farmers who very much want more relaxed standards toward pesticides like those that US farmers enjoy. There are protests and contending points of view. But in Europe, it remains the responsibility of the chemical companies to demonstrate, with peer reviewed studies, that the chemical they want to introduce into the European environment is safe. This is very different from the system we have in the US in which biased studies let chemical companies put new products on the market and it becomes the responsibility of citizens to prove, on a case by case basis and one chemical at a time, that the chemical has caused harm to them.

Our system employs what some call the whack a mole principle in which US citizens must attempt to remove one by one dangerous chemicals from the market in an unending, expensive and highly illogical legal process. The other alternative is to rely on the punishingly slow process of having the EPA test tens of thousands of untested chemicals–at the rate of approximately 20 per year–an approach that the underfunded EPA will need centuries to accomplish.

The US could at least halt the introduction of new and potentially dangerous chemicals into the environment if it adopted the Precautionary Principle. Unfortunately, powerful economic and political forces all but guarantee that such an action will not happen. However, I want to return here to Robinson’s article that points out how research physicians, epidemiologists and chemists have been publishing peer reviewed articles for decades demonstrating the deadly link between about 100 especially dangerous chemicals and cancer. Could we begin by banning these 100 chemicals that have already been proven to cause terrible harm?.

Mounting an attempt to ban even 100 out of tens of thousands of US chemicals would be met with incredibly well funded campaigns to discredit those who are asking for such a modest beginning at improving environmental health and safety in the US. This approach might take more than a generation to accomplish. It might require that coalitions of different kinds of environmental, health, legal, community and monied interests leave their silos and agree to work together for the greater good. But more than that, it would require a profound attitude shift in American citizens, which is where this article has been attempting to go all along.

The Answer to Wealth and Influence in the US: Your Voice and Your Body

One of the questions I’ve been wanting to ask my oncologist, but haven’t yet voiced, is what environmental and public health organizations he supports. It seems to me that if he is going to make a good living treating people for cancers, many of which are caused by our polluted environments, he needs to demonstrate his commitment to changing the conditions that make his work necessary. Environmental writer Sandra Steingraber argues that far too many cancers are caused by environmental pollution. Not that cancer would disappear if we were all able to live in pristine environments. The complexity of our human bodies means that we have far greater risks of naturally occurring genetic mutations that lead to cancer than simpler organisms. What I would hope from oncologists would be that they would use their influence and resources to support efforts to have environmental toxins in our environment greatly reduced. I would also ask that they add one step to their intake documents; they need to ask patients for environmental histories in addition to family health histories. They need to document what environmental toxins have been part of their patients’ lives.

Many years ago I had a conversation with a woman running a small town Arts Council. I asked if she’d always worked on arts advocacy. No, she said. Her first career was working with the American Cancer Society, work she embarked on with idealistic ideas of wiping out lung cancer, for one thing. As she rose in the ranks of the organization and learned more about it and about the forces arrayed against it, she came to a terrifying conclusion. She suspected the ACS was focused on finding a cure for cancer because the approach meant that its existence as an organization would be guaranteed for a very long time. Her organization’s focus on finding the causes for cancers most often related to family histories and the lifestyle choices that could be contributing to health problems: smoking, obesity, poor diet. Her conclusion after looking at the complex dance between government, industry, the health care system and health advocacy, was that all four needed each other in order to survive. That, she concluded, was why there was so little emphasis on discovering and eliminating the environmental causes of cancer. To eliminate cancer’s causes would mean the need for the ACS would disappear. Not long after reaching that conclusion, she resigned from the ACS and embarked on a career focused on arts advocacy. At least, working in the arts, she felt she would do no harm.

There are so many ways for people, well meaning people, to work on environmental issues that actually provide only window dressing. Whether it is the PR efforts of the environmental people in chemical companies who distribute beautiful color brochures demonstrating how they greenwash the dangers of the chemicals they produce, or lawmakers who–as Obama and bipartisan senators and representatives did–claim a victory when they overhaul the Toxic Chemicals Act, only to design an approach, as I mentioned above, that will require centuries for the EPA to accomplish, or advocacy organizations to focus only on incremental victories that will never threaten to rock the cultural boat, organizations can appear very busy while accomplishing very little.

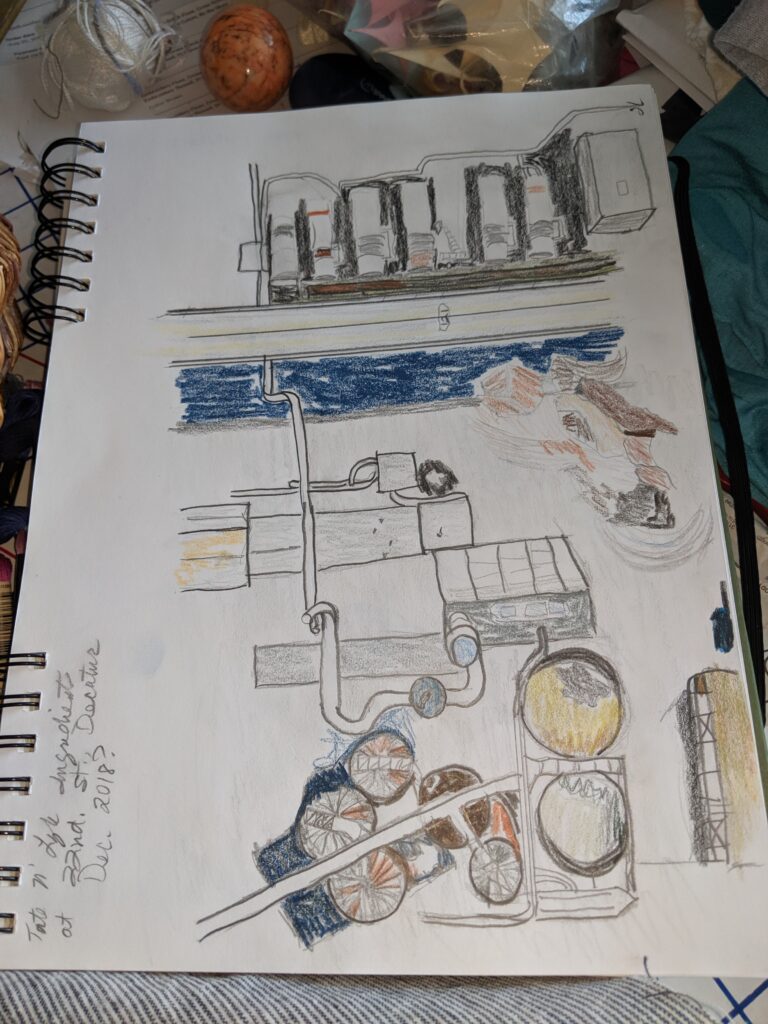

The author’s freehand drawing of the “web” of grain processing silos near where she once lived. Photo credit: Sandra Lindberg

There are other ways to work on the problems we face–and there are groups doing such work. They have succeeded in ignoring messages intended to make them feel powerless.

As individuals it is easy to become convinced that one person’s efforts can never amount to much. The messaging from countless magazines, newspapers, press releases, billboards, and on-line sites happily encourages our belief in powerlessness. These sources are invested in keeping our ailing culture largely the way it is. Whether it is the article arguing that the world is going to fall apart if fossil fuels and their byproducts are not allowed to continue, or a pollster intent on convincing us that outlier candidates don’t have a chance in hell of getting elected–and thereby of course influencing the political outcome to agree with the pollster’s prediction– we are inundated with messages intent on convincing us that we waste our time as activists.

Many folks are so worried about the unraveling of US health care that they despair of ever changing current conditions. However, the US has known another time much like this one. During the Gilded Age following the Civil War, political corruption and cronyism dominated Washington DC. It was the era of a handful of incredibly wealthy plutocrats. From 1865 to 1900 many people earned below the poverty level of $500 per year. And then conditions finally became so terrible that people rose up. The Progressive Movement was born. In a single year 1100 labor unions went on strike. In fact, the power of the people began to strike fear into even the kinder politicians, like Theodore Roosevelt who relished breaking apart trusts, and Franklin D. Roosevelt who devised the New Deal to rein in corporate greed and guarantee working people somewhat better lives.

The work of 19th Century Progressives needs to be remembered. What was accomplished then needs to be furthered–and fast. Our times are getting truly bad: environmental degradation, illness, a broken healthcare system, poverty, a truly greedy 1%, and the catastrophic effects they are happy to bring us, including climate change.

I am arguing that the messages that insist we are powerless are only one way to see the world. The other way is to remind ourselves over and over again that the 1% in the US are very few in number. Even those who rely on their dollars to pay their manager salaries or to get them elected, are relatively few in number. We, on the other hand, are the majority. We who suffer from and must pay for treatment from the ill effects of, to name only one of many evils, chemical environmental pollution, are many. We have friends and families. And though our growing numbers dishearten us, our swelling ranks offer opportunity, too.

The next time someone who learns of your cancer diagnosis encourages you to laugh at cancer, fight cancer, or enjoy the time you have left for as long as you can, you can reframe that thought so the focus moves beyond the personal, “That’s only part of what I’m doing. With my remaining time I’m doing what I should have been doing all my life. I’m reaching out to all those environmental organizations with bold aspirations, those physician advocacy organizations or the research physicians and epidemiologists determined to provide proof of the deadly connection between certain chemicals and cancer, or those community organizations blocking traffic or causing work stoppages at chemical sites and fossil fuel sites to demand cleaner environments for their people. My last days will be used to add my voice and, if possible, my body, to that work so that there is one more person on the internet, on the phone, or in a senator’s or CEO’s office making a contribution to groups who have been fighting for years. Or as in my case, let me take inspiration from muckraker writers of the Gilded Age who exposed the punishing conditions of their time. Let me be one more writer determined to provide better information about the personal, socio-economic and political aspects of a cancer like mine.

Photo credit: Spider web image manipulated on Dragonfly platform by Isaac Galewsky

No matter how much we have convinced ourselves that we are individuals and that we can somehow keep ourselves safe without the support of countless others, we live within a complex web of interconnections. Some parts of the web are incredibly nurturing, and others cause us suffering. The only way to heal this system of interrelationships of ours is to acknowledge how much we are connected to each other, how much we need each other, and how strong we will become when we stand together. This article is my first attempt to convey what I have researched about AML’s links to environmental toxins. My hope is that what I have shared here will convince others of the powerful opportunity we all have to rise up against prevailing messages intent on keeping us powerless, and to experience in the company of others our ability to effect change. May we all have strong hearts and loving companions for such a journey.

I would like to thank Roslyn O’Connor, one of my readers for this piece. She provided valuable feedback I trust regarding environmental aspects of the story. She is an Environmental Studies and Biology Instructor at Millikin University in Decatur, IL, and can be reached at [email protected].

I would also like to thank my other readers, both friends and family, who were Ingrid Lindberg, painter and collage artist; Melinda Lindberg, lawyer (retired); Jenny Stern, physician (retired); Sam Galewsky, molecular and cell biologist at Millikin University; Isaac Galewsky, undergrad studying renewable energy.

Sources:

Clapp, R., Jacobs, M., & Loechler, E. L. (2008). Environmental and Occupational Causes of Cancer: New Evidence 2005-2007. Reviews on Environmental Health, 23(1), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1515/reveh.2008.23.1.1

Contributor, D. F. C. O. (2021, May 24). The Hill. The Hill. https://thehill.com/opinion/energy-environment/555145-the-terrible-environmental-cost-of-stagnant-epa-funding/

Hofverberg, E. (2022, April 14). The history of the elimination of leaded gasoline | In custodia legis. The Library of Congress. https://blogs.loc.gov/law/2022/04/the-history-of-the-elimination-of-leaded-gasoline/

It could take centuries for EPA to test all the unregulated chemicals under a new landmark bill. (2016, June 22). PBS NewsHour. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/science/it-could-take-centuries-for-epa-to-test-all-the-unregulated-chemicals-under-a-new-landmark-bill

Key Statistics for Acute Myeloid Leukemia (AML). (n.d.). American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/acute-myeloid-leukemia/about/key-statistics.html

Obama signs major overhaul of toxic chemicals rules into law. (2016, June 22). PBS NewsHour. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/health/obama-to-sign-first-toxic-chemical-rules-overhaul-in-40-years

Poynter, J. N., Richardson, M., Roesler, M. A., Blair, C. K., Hirsch, B. A., Nguyen, P. L., Cioc, A., Cerhan, J. R., & Warlick, E. D. (2016). Chemical exposures and risk of acute myeloid leukemia and myelodysplastic syndromes in a population‐based study. International Journal of Cancer, 140(1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.30420

Resilience. (2024, March 11). The Great Unwinding: the failing battle for health and healthcare in these all too disunited states. Resilience. https://www.resilience.org/stories/2024-03-11/the-great-unwinding-the-failing-battle-for-health-and-healthcare-in-these-all-too-disunited-states/

Resilience. (2023, October 13). Sacrifice Zones’: the new ‘Jim Crow’ that’s sickening and killing people of color. Resilience. https://www.resilience.org/stories/2023-10-13/sacrifice-zones-the-new-jim-crow-thats-sickening-and-killing-people-of-color/

Revised recommendation for an occupational exposure standard for benzene. (1976, August 1). https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/19373

Richardson, J. (2021, November 30). Benzene, the need for a new global Industrial Revolution and the big challenges that lie ahead – Asian Chemical Connections. Asian Chemical Connections. https://www.icis.com/asian-chemical-connections/2021/11/benzene-the-need-for-a-new-global-industrial-revolution-and-the-big-challenges-that-lie-ahead/

Syndax Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (2024, January 2). Syndax Highlights Recent Updates and Anticipated 2024 Milestones. prnewswire.com. Retrieved March 4, 2024, from https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/syndax-highlights-recent-updates-and-anticipated-2024-milestones-302024253.htm

The precautionary principle | EUR-Lex. (n.d.). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/EN/legal-content/summary/the-precautionary-principle.htm

Wealth distribution U.S. 2023 | Statista. (2023, December 20). Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/203961/wealth-distribution-for-the-us/

What is benzene? – YnFx. (2020, November 11). YnFx. https://www.yarnsandfibers.com/textile-resources/synthetic-fibers/nylon/nylon-production-raw-materials/what-is-benzene/