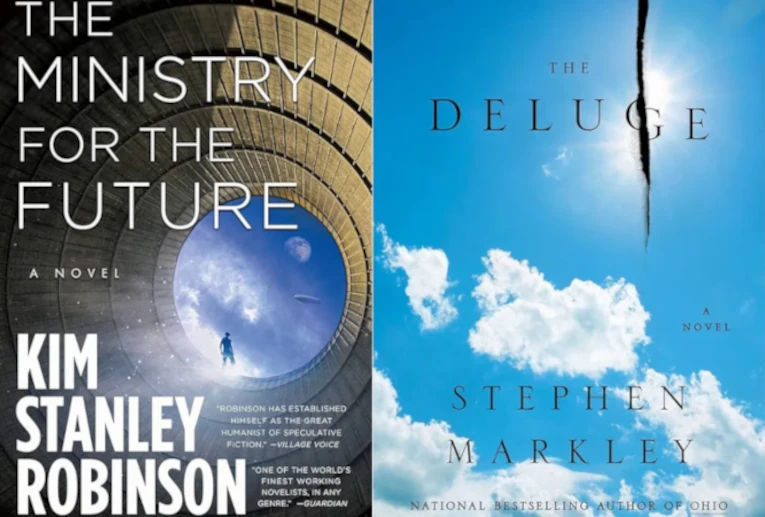

A comparative review of the climate fiction books “The Ministry for the Future” by Kim Stanley Robinson and “The Deluge”, by Stephen Markley.

Sci-fi is never really about the future. It’s about the present, reworking and rediting reality. Sci-fi is a reflection of present conditions and our social reactions to them, left to run off into an undetermined future. In this way, the genre not only helps us parse out the potential future significance of current events, but also the contemporary significance of them.

So where does climate fiction fit into this picture?

In a way, it fits very awkwardly. With climate science so wrapped up in prediction and modelling, fiction cannot help but muddy this politically fraught quagmire. There is no more notorious example of this than Michael Crichton, (author of the Jurassic Park novels) and his book State of Fear. The novel was a climate denialist tract that, alongside his personal advocacy, helped convince George W. Bush to sabotage and roll back climate action. Yet even fiction that accepts climate change can minimise its threat. Kim Stanley Robinson’s earlier book Green Mars underplays climate change as a relatively benign, manageable crisis. As his later work amply demonstrates, KSR woke up to the danger. All the same, bad fiction can harm real-world action.

In another way, cli-fi fits sublimely into its parent genre. Current climate action (or lack of it) influences the future in a way other historical phenomena never have. Climate science, let alone fiction, is focused on current trends precisely because of their future impacts. Here, cli-fi can be seen as a fruitful vision into where current decision-making may lead us.

Climate fiction reflects the reality and potential of the present moment like few other works of fiction can. This being the case, how do two of the genre’s foundational novels, published less than three years apart, seem to have emerged from such differing eras?

The Ministry for the Future

‘The Ministry for the Future’ was written by KSR and was published in 2020. It follows various characters within and adjacent to the eponymous ministry, a UN body created to combat the climate crisis.

Zurich, via Unsplash

With detours around the globe, it is primarily based in the Ministry’s Zurich headquarters, following a series of bureaucrats, policymakers, activists, and scientists (and occasional disembodied Socratic dialogues) as they scrabble to find and implement solutions against inertia, adversaries, and the unfolding breakdown itself.

It is a hard sci-fi novel. All the science and technology held within either exist in some form already, or are theoretically plausible according to current understandings. Most of the policies and political movements within likewise diverge little from current practices. There are a few notable exceptions, but at the time the book was written, even its more utopian aspects could be said to exist at least in primordial forms.

The Deluge

‘The Deluge’ was written by Stephen Markley and published in 2023. It follows a cast of US characters living through and reacting to climate breakdown amidst a wider social and economic crisis.

San Francisco Wildifre, via Unsplash

As in The Ministry of the Future, there are scientists and policymakers, but most of the cast is a motley crew of activists, drug addicts, marketing gurus, investment magnates, and terrorists — as well as a few relatively ordinary people, swept up in extraordinary times.

Deluge is less strictly cli-fi, and more a speculative fiction novel for its scope — though it never fully departs from science fiction either. The social and political movements it presents could sound far-fetched if read without context, but at near-900 pages, the novel is a slow, gradational story. You are led through an unfolding history, each event building on the last and constantly buffeted by the inexplicable intervention of climate change. One of the masterful strokes of the Deluge is that even when the unthinkable happens, you can be shocked, but never surprised.

Time Capsules

Both books are epics in their own right — engrossing, challenging plunges into humanity’s hot, unstable future. Their insights are intriguing extrapolations of current science. They portray lurid disasters and the chaos they engender. They also showcase the ways dramatic history is felt on a personal level. Economic strife, mental illness, and simple confusion suffuse both — though there are distinctions. The Ministry for the Future is an in-depth portrayal of the ways institutions scramble to combat crises. Whilst The Deluge too involves high politics, it is a much more human, quotidian portrayal of life under climate breakdown. Its most deeply impacted character is scarcely aware — outside its visceral impacts — of what climate change even is, his constant lament:

“You can’t shake the feeling that you never know what’s going on.”

As portrayals of the future, they are both immensely useful books. Helping us parse through, evaluate, and cognitively prepare for impacts that are very likely on their way. And, perhaps more usefully, mapping out how we might respond. Ministry in particular has even engendered serious engagement from economists and policymakers, considering if its fictional policy measures — such as currency tied to sequestered carbon — could be turned into real policy.

What is more striking, however, is when we look at both books as representations of the present. Or rather, their presents. They were built out of a perception of the world at the time they were published. Despite only being published 3 years apart, Deluge and Ministry feel as if they are emerging from very different eras. Each emerging on either side of a watershed moment, their futures born out of very different presents.

Controlling Chaos

Ministry for the Future was published at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. This certainly helped its popularity, in the sense that millions of people suddenly had a lot more time to read it. It also helped its message. As KSR himself wrote of the COVID-19 pandemic:

“We’re now confronting a miniature version of the tragedy of the [climate crisis]. We’ve decided to sacrifice over these months so that, in the future, people won’t suffer as much as they would otherwise.”

Though many nations and governments were paralysed by indecision and chaotic responses, rapid mass economic programs — lockdowns, furlough schemes, and vaccinations — were implemented on a scale scarcely seen outside wartime mobilizations.

Covid global hotspots in March, 2020, via Unsplash

The COVID-19 responses engendered a sense that government, scientists, and citizens could collectively combat a global crisis. Technocratic wisdom was combined with grassroots movements, and international cooperation was put ahead of rivalry. This is a rosy picture, the experience and outcome of the Covid-19 pandemic was far from perfect. Yet at the time it seemed as if, at least as an ideal, civilization had the power to collectively mobilize for a crisis.

This wider context served to give weight to Ministry’s immanent philosophy. Though the novel’s eponymous Ministry has a much more tortured journey to controlling the crisis, this is to be expected of a problem on the scale of climate change. Mass mortality, eco-terrorism, interstate conflict, and assassination dog the tale.

Even in Ministry’s more lurid details, we see hints of this sublime cooperation. The eco-terrorism in the novel is never really an antagonistic element to the technocratic movement, but rather its shadow. Taking the fight against climate change to places where the Ministry cannot. This can be contrasted with The Deluge, where eco-terrorism is portrayed as deeply antagonistic, even to those who share its end goals.

Climate protests, via Unsplash

This feature, alongside more normal grassroots movements cooperating with governments, banks, and the ministry, shows the novel’s theory of change. Wide swathes of society can ally together to overcome key vested interests and combat the crisis.

Even if one disputes the plausibility of this approach, it is undeniable that any effective climate response will require a movement across social, institutional, economic, and geographical lines. What made Ministry for the Future so compelling was that it emerged at a moment when this future seemed within our grasp.

Ambiguous Dystopia

The Deluge was published in a very different world.

The COVID-19 pandemic was over, but mainly in the sense that widespread political programs had ended. Infection and death rates were still high, and the economic impact of long-covid was growing. Cooperation had ended, but the crisis had not.

Bucha, via wikimedia commons

In 2023, Geopolitics was becoming multipolar. Cooperation declined, with tensions and outright war on the rise. Trump had left the White House, but the alternative was simply another administration that fueled growing oligarchic power. The shockwaves of the Trump era never subsided, and Christian nationalism had entered the agenda in its wake. Interest rates went up and down, energy shocks came and went, and despite the fact that most indicators suggested the economy improved post-COVID, everyone felt worse off. This was the Vibecession. The social contract which demanded growth in order to deliver happiness was falling apart.

2023 was also a year of geological significance for climate change. The hottest year for over 120,000 years, the temperature anomaly reaching within a rounding error of the 1.5°C target, and going as high as an average 1.7°C in the final months. Statistics started translating into events. Antarctic ice declined, permafrost melted, wildfires exploded, and floods inundated entire nations.

In short, The Deluge was published in an uncertain world where the crises (plural this time) seemed beyond our ability to tackle. Rather than cooperate, we fought.

The Deluge’s setting begins around 2014, so the readers re-live the transition from order to chaos along with the characters. It blows through these years building its character backgrounds. By 2030, climate change is having severe impacts just as political responses to it are falling apart, attention drained away by domestic terrorism and worsening economic conditions. As the years advance we watch movements rise and fall, coalitions build and then dissipate. Most of the key crises within the book existed during 2023, but in The Deluge continued to exacerbate without solutions. Similarly, the same political sensibilities that constrain movement now do so in the book. Necessary action is delayed because it might spook the market, and when change seems on the horizon, armies of lobbyists emerge to block it — or water it down into tokenistic insignificance.

By Mike Lewelling, National Park Service

The inescapability of mainstream ‘market logic’, even as it drives increasingly crippling disasters, is a key theme of The Deluge. This is exactly the position of the world in 2023. The climate crisis was ramping up, sustainable development was failing and geopolitics was growing distinctly confrontational — yet what Daniela Gabor calls the ‘Wall Street Consensus’ still reigned. This doctrine favours market capital in climate development solutions, at the expense of regulation, workers’ rights, and political deliberation. Most importantly, state money needs to be put up to take the risk away from private actors. The Market is the focus, and it can’t be allowed to lose. Where this logic eventually takes us is what The Deluge shows.

Other trends of 2023 are taken to their logical conclusions, whether they succeed or break under their own contradictions. The opioid crisis, the hollowing out of state capacity, oligarchic power, populism, militant activism, Christian nationalism, AI and many more get a turn in this daunting tale.

The book’s conclusion mirrors its innate theory of change. Many of the (perceived) positive political trends of today hold in them the seeds of their own failure. Though massive action is implemented by the end of the novel, the near-miss apocalypse has left America a very different place — and whether it has avoided this fate or simply delayed it is an open question. The future seems as open to destruction as it does deliverance.

This outlook not only concludes The Deluge, but represents the zeitgeist it emerged within.

Different Worlds, Different Paths

Both novels are deeply grounded in reality, and all of the phenomena they portray exist in some form already. Which of our current trends lives and dies is what sets them apart. The birth era of Ministry could plausibly claim the forces of progress were on track to win out. For the Deluge, hope remained undiminished, but the weight of reality presented an ever more daunting vista of days to come.

Via Unsplash

If we are to take anything from a comparison of these two books, it is that the world is changing rapidly. Climate change is accelerating, and the political landscape to combat it is mired in the tumult of a Polycrisis. What will the outlook look like in another 3 years? Will a new time of global cooperation convince us that the struggle against climate change — and the alliances it requires — can be achieved? Or will the next wave of climate disasters and conflict create a future to fear?

Yet we should be cautious in concluding the inevitable and accelerating breakdown of our future prospects. This is where the context of narrative becomes important. Whilst both books emerge in times with demonstrably different material conditions, the primary shift was of narrative. For all the talk of deglobalization, global trade is still larger than it was pre-pandemic. The sudden spike in global temperatures of 2023 can be (in part) tied to shipping regulations initiated in 2020. The underlying material forces of the world change much more languidly than our narrative understandings of them. Deluge and Ministry capture the trajectory of their contemporary narratives much more than they do shifts in political economy and biophysical conditions. The seemingly epochal rift between the two represents how quickly our global society can alter its understanding of itself. Our civilizational pathway is always inseparable from the fate of the wider planet, but neither does it walk in lockstep. Climate fiction novels can help us see the way we are going, and help us question — knowing the world that lies ahead — if this is the right road to embark upon.