In Western countries, feminist history is generally packaged as a story of “waves”. The so-called first wave lasted from the mid-19th century to 1920. The second wave spanned the 1960s to the early 1980s. The third wave began in the mid-1990s and lasted until the 2010s. Finally, some say we are experiencing a fourth wave, which began in the mid-2010s and continues now.

The first person to use “waves” was journalist Martha Weinman Lear, in her 1968 New York Times article, The Second Feminist Wave, demonstrating that the women’s liberation movement was another “new chapter in a grand history of women fighting together for their rights”. She was responding to anti-feminists’ framing of the movement as a “bizarre historical aberration”.

Some feminists criticise the usefulness of the metaphor. Where do feminists who preceded the first wave sit? For instance, Middle Ages feminist writer Christine de Pizan, or philosopher Mary Wollstonecraft, author of A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792).

Does the metaphor of a single wave overshadow the complex variety of feminist concerns and demands? And does this language exclude the non-West, for whom the “waves” story is meaningless?

Despite these concerns, countless feminists continue to use “waves” to explain their position in relation to previous generations.

The first wave: from 1848

The first wave of feminism refers to the campaign for the vote. It began in the United States in 1848 with the Seneca Falls Convention, where 300 gathered to debate Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s Declaration of Sentiments, outlining women’s inferior status and demanding suffrage – or, the right to vote.

It continued over a decade later, in 1866, in Britain, with the presentation of a suffrage petition to parliament.

This wave ended in 1920, when women were granted the right to vote in the US. (Limited women’s suffrage had been introduced in Britain two years earlier, in 1918.) First-wave activists believed once the vote had been won, women could use its power to enact other much-needed reforms, related to property ownership, education, employment and more.

White leaders dominated the movement. They included longtime president of the the International Woman Suffrage Alliance Carrie Chapman Catt in the US, leader of the militant Women’s Social and Political Union Emmeline Pankhurst in the UK, and Catherine Helen Spence and Vida Goldstein in Australia.

This has tended to obscure the histories of non-white feminists like evangelist and social reformer Sojourner Truth and journalist, activist and researcher Ida B. Wells, who were fighting on multiple fronts – including anti-slavery and anti-lynching – as well as feminism.

The second wave: from 1963

The second wave coincided with the publication of US feminist Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique in 1963. Friedan’s “powerful treatise” raised critical interest in issues that came to define the women’s liberation movement until the early 1980s, like workplace equality, birth control and abortion, and women’s education.

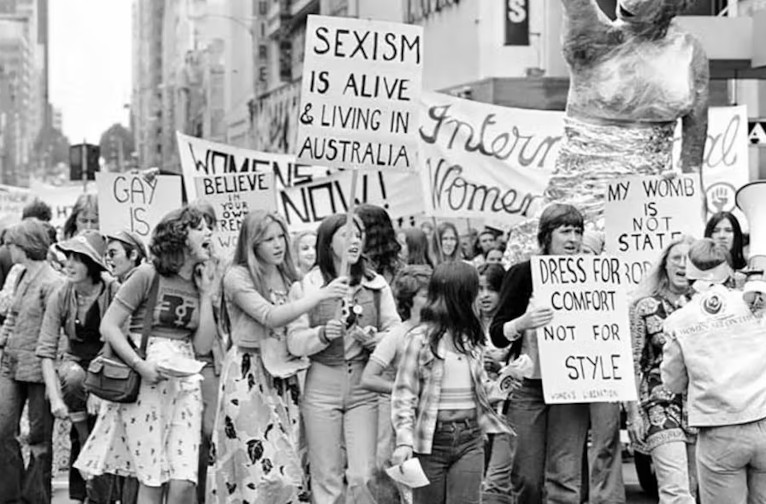

Women came together in “consciousness-raising” groups to share their individual experiences of oppression. These discussions informed and motivated public agitation for gender equality and social change. Sexuality and gender-based violence were other prominent second-wave concerns.

Australian feminist Germaine Greer wrote The Female Eunuch, published in 1970, which urged women to “challenge the ties binding them to gender inequality and domestic servitude” – and to ignore repressive male authority by exploring their sexuality.

Successful lobbying saw the establishment of refuges for women and children fleeing domestic violence and rape. In Australia, there were groundbreaking political appointments, including the world’s first Women’s Advisor to a national government (Elizabeth Reid). In 1977, a Royal Commission on Human Relationships examined families, gender and sexuality.

Amid these developments, in 1975, Anne Summers published Damned Whores and God’s Police, a scathing historical critique of women’s treatment in patriarchal Australia.

At the same time as they made advances, so-called women’s libbers managed to anger earlier feminists with their distinctive claims to radicalism. Tireless campaigner Ruby Rich, who was president of the Australian Federation of Women Voters from 1945 to 1948, responded by declaring the only difference was her generation had called their movement “justice for women”, not “liberation”.

Like the first wave, mainstream second-wave activism proved largely irrelevant to non-white women, who faced oppression on intersecting gendered and racialised grounds. African American feminists produced their own critical texts, including bell hooks’ Ain’t I a Woman? Black Women and Feminism in 1981 and Audre Lorde’s Sister Outsider in 1984.

The third wave: from 1992

The third wave was announced in the 1990s. The term is popularly attributed to Rebecca Walker, daughter of African American feminist activist and writer Alice Walker (author of The Color Purple).

Aged 22, Rebecca proclaimed in a 1992 Ms. magazine article: “I am not a post-feminism feminist. I am the Third Wave.”

Third wavers didn’t think gender equality had been more or less achieved. But they did share post-feminists’ belief that their foremothers’ concerns and demands were obsolete. They argued women’s experiences were now shaped by very different political, economic, technological and cultural conditions.

The third wave has been described as “an individualised feminism that can not exist without diversity, sex positivity and intersectionality”.

Intersectionality, coined in 1989 by African American legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw, recognises that people can experience intersecting layers of oppression due to race, gender, sexuality, class, ethnicity and more. Crenshaw notes this was a “lived experience” before it was a term.

In 2000, Aileen Moreton Robinson’s Talkin’ Up to the White Woman: Indigenous Women and Feminism expressed Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women’s frustration that white feminism did not adequately address the legacies of dispossession, violence, racism, and sexism.

Certainly, the third wave accommodated kaleidoscopic views. Some scholars claimed it “grappled with fragmented interests and objectives” – or micropolitics. These included ongoing issues such as sexual harassment in the workplace and a scarcity of women in positions of power.

The third wave also gave birth to the Riot Grrrl movement and “girl power”. Feminist punk bands like Bikini Kill in the US, Pussy Riot in Russia and Australia’s Little Ugly Girls sang about issues like homophobia, sexual harassment, misogyny, racism, and female empowerment.

Riot Grrrl’s manifesto states “we are angry at a society that tells us Girl = Dumb, Girl = Bad, Girl = Weak”. “Girl power” was epitomised by Britain’s more sugary, phenomenally popular Spice Girls, who were accused of peddling “‘diluted feminism’ to the masses”.

Riot Grrrrl sang about issues like homophobia, sexual harassment, misogyny and racism.

The fourth wave: 2013 to now

The fourth wave is epitomised by “digital or online feminism” which gained currency in about 2013. This era is marked by mass online mobilisation. The fourth wave generation is connected via new communication technologies in ways that were not previously possible.

Online mobilisation has led to spectacular street demonstrations, including the #metoo movement. #Metoo was first founded by Black activist Tarana Burke in 2006, to support survivors of sexual abuse. The hashtag #metoo then went viral during the 2017 Harvey Weinstein sexual abuse scandal. It was used at least 19 million times on Twitter (now X) alone.

In January 2017, the Women’s March protested the inauguration of the decidedly misogynistic Donald Trump as US president. Approximately 500,000 women marched in Washington DC, with demonstrations held simultaneously in 81 nations on all continents of the globe, even Antarctica.

In 2021, the Women’s March4Justice saw some 110,000 women rallying at more than 200 events across Australian cities and towns, protesting workplace sexual harassment and violence against women, following high-profile cases like that of Brittany Higgins, revealing sexual misconduct in the Australian houses of parliament.

Given the prevalence of online connection, it is not surprising fourth wave feminism has reached across geographic regions. The Global Fund for Women reports that #metoo transcends national borders. In China, it is, among other things, #米兔 (translated as “rice bunny”, pronounced as “mi tu”). In Nigeria, it’s #Sex4Grades. In Turkey, it’s #UykularınızKaçsın (“may you lose sleep”).

In an inversion of the traditional narrative of the Global North leading the Global South in terms of feminist “progress”, Argentina’s “Green Wave” has seen it decriminalise abortion, as has Colombia. Meanwhile, in 2022, the US Supreme Court overturned historic abortion legislation.

Whatever the nuances, the prevalence of such highly visible gender protests have led some feminists, like Red Chidgey, lecturer in Gender and Media at King’s College London, to declare that feminism has transformed from “a dirty word and publicly abandoned politics” to an ideology sporting “a new cool status”.

Where to now?

How do we know when to pronounce the next “wave”? (Spoiler alert: I have no answer.) Should we even continue to use the term “waves”?

The “wave” framework was first used to demonstrate feminist continuity and solidarity. However, whether interpreted as disconnected chunks of feminist activity or connected periods of feminist activity and inactivity, represented by the crests and troughs of waves, some believe it encourages binary thinking that produces intergenerational antagonism.

Back in 1983, Australian writer and second-wave feminist Dale Spender, who died last year, confessed her fear that if each generation of women did not know they had robust histories of struggle and achievement behind them, they would labour under the illusion they’d have to develop feminism anew. Surely, this would be an overwhelming prospect.

What does this mean for “waves” in 2024 and beyond?

To build vigorous varieties of feminism going forward, we might reframe the “waves”. We need to let emerging generations of feminists know they are not living in an isolated moment, with the onerous job of starting afresh. Rather, they have the momentum created by generations upon generations of women to build on.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.