This story was originally published by Barn Raiser, your independent source for rural and small town news.

Diverse groups join forces to bolster the native seed supply for ecological restoration.

Land managers and restoration practitioners have long been concerned about the scarcity of native seeds required for restoring ecosystems. Whether sourced from soil seed banks, existing native plant populations or commercial vendors, the demand for native seeds consistently outstrips the available supply.

Native seed production plots at the Hickories Farm, Ridgefield, Connecticut.

In January 2023, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine released a 228-page report, underscoring the urgent need to increase native seed supplies to restore damaged ecosystems in the United States. The report found that the country’s current supply of native seeds is already insufficient to meet the restoration needs of agencies like the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). “Time is of the essence,” the report states, “to bank the seeds and the genetic diversity our lands hold.”

Not coincidentally, in 2023, the United States faced its costliest year on record for climate-related disasters, totaling nearly $100 billion in estimated damages, with millions of acres of land degraded. Experts predict the ongoing degradation of ecosystems from the persistent stresses of urbanization, landcover conversion, invasive species, pollution, and mineral extraction will only compound more frequent and extreme weather events fueled by climate change.

This, in turn, will create an even greater need for native seeds and plants, which play a pivotal role in ecosystem restoration by helping mitigate and repair the impacts of such mega-disasters. A key element of restoration involves using native seed and plant materials, like bulk seeds or tree saplings, in areas affected by damage. This helps expedite the recovery and rehabilitation of an ecosystem’s structure, composition and function.

When restorative activities reach hundreds to thousands of hectares by means of one large-scale project or many small-scale projects, nursery growers will need to produce hundreds of thousands of kilograms of seeds and billions of individual plant saplings. For example, in Minnesota, land managers used more than 500,000 kg (1,100,000 lb.) of seed to restore 9,000 hectares of northern tallgrass prairies. Whereas, in Massachusetts, the restoration of wetlands, streams and sandplain grasslands can require between 5,000 and 50,000 native plants and seeds per project.

Seed Supply Chains

Meeting the present and future demand for native seed and plant material is constrained by the fact that wild populations are often the only source for seeds and cuttings, a practice that has strained already fragmented ecosystems. A more ethical, practical and economical solution is one that brings native species into horticultural and agricultural production to multiply seeds and create various forms of propagated planting stock.

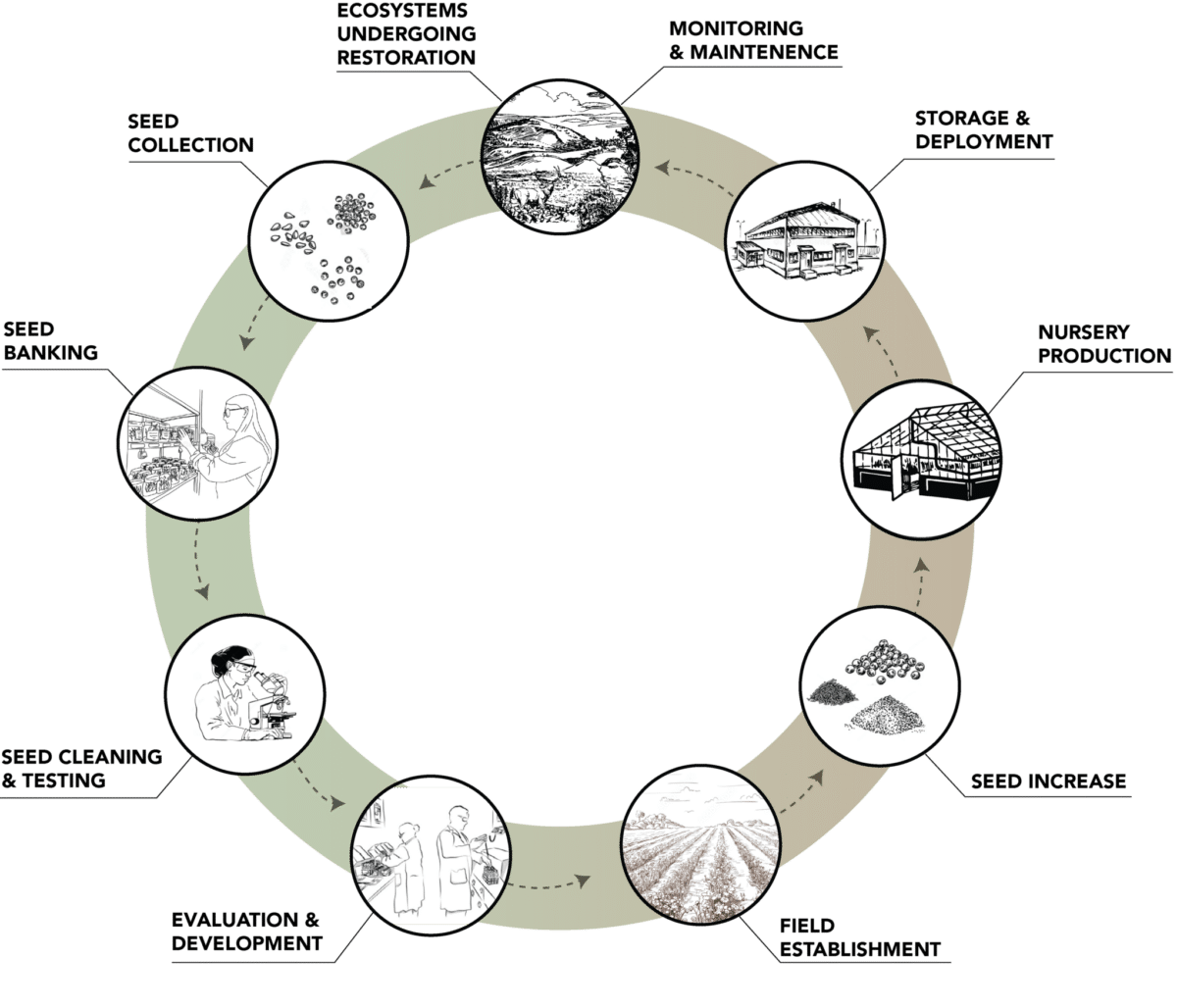

In recent years, land management and restoration experts have pushed for such a shift using the framework of a supply chain. A supply chain is a complete system involving people, resources, information and activities to facilitate the transformation of raw materials into a final product or service. In the context of ecological restoration, seed supply chains encompass everything from conserving habitats and safeguarding plant genetic resources to collecting and cultivating seeds. As a result, the interconnected stages of germination, cultivation, harvesting, processing, cleaning and storage need to be considered. These stages are crucial for multiplying seeds and generating commercially viable quantities of both seeds and containerized planting stock.

Some of the key steps required to multiply seed material and produce commercially viable quantities of both seed and planting stock for practitioners and land managers working on a range of restorative activities across a wide spectrum of ecosystem types. (Ecological Health Network)

The Northeast Seed Network

At the heart of the issue of inadequate seed supply in the Northeastern and Northern Mid-Atlantic states is another enduring problem: the concentration of federal land ownership in the Western United States.

While the amount of land owned by the federal government varies widely between states—ranging from 0.3% of land in Connecticut to 80% of land in Nevada—the government owns roughly 46% of land in the 11 coterminous Western states in contrast with 4.6% of land in the other states. The federal government is also the nation’s biggest buyer of native seeds (through agencies like the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management). In 2020 alone, BLM field offices purchased about 1.5 million pounds of seed to restore land destroyed by wildfires. This results in a notable procurement gap in Eastern states, where state governments and private individuals own most of the land. However, despite variations in land ownership and biogeography across the country, Eastern and Western states share challenges, such as the demand for seeds on a large scale and the necessity for seeds in response to environmental disasters, including floods, droughts and invasive species.

Producing native seeds at scale in the East is often more expensive because farmer’s landholdings tend to be smaller than in the Midwest or West. However, despite this, many dedicated stakeholders, including the Mid-Atlantic Regional Seed Bank (MARS-B), the Native Plant Trust, the Ecotype Project, eco59, Pinelands Nursery, Planters’ Choice, the Highstead Foundation, Wild Seed Project and Hilltop Hanover Farm have long been working on generating supplies of seed and plant material for Northeast and Northern Mid-Atlantic states. However, strengthening the region’s supply chain to meet the growing demand for ecological restoration activities is too big of a job for any entity to tackle independently.

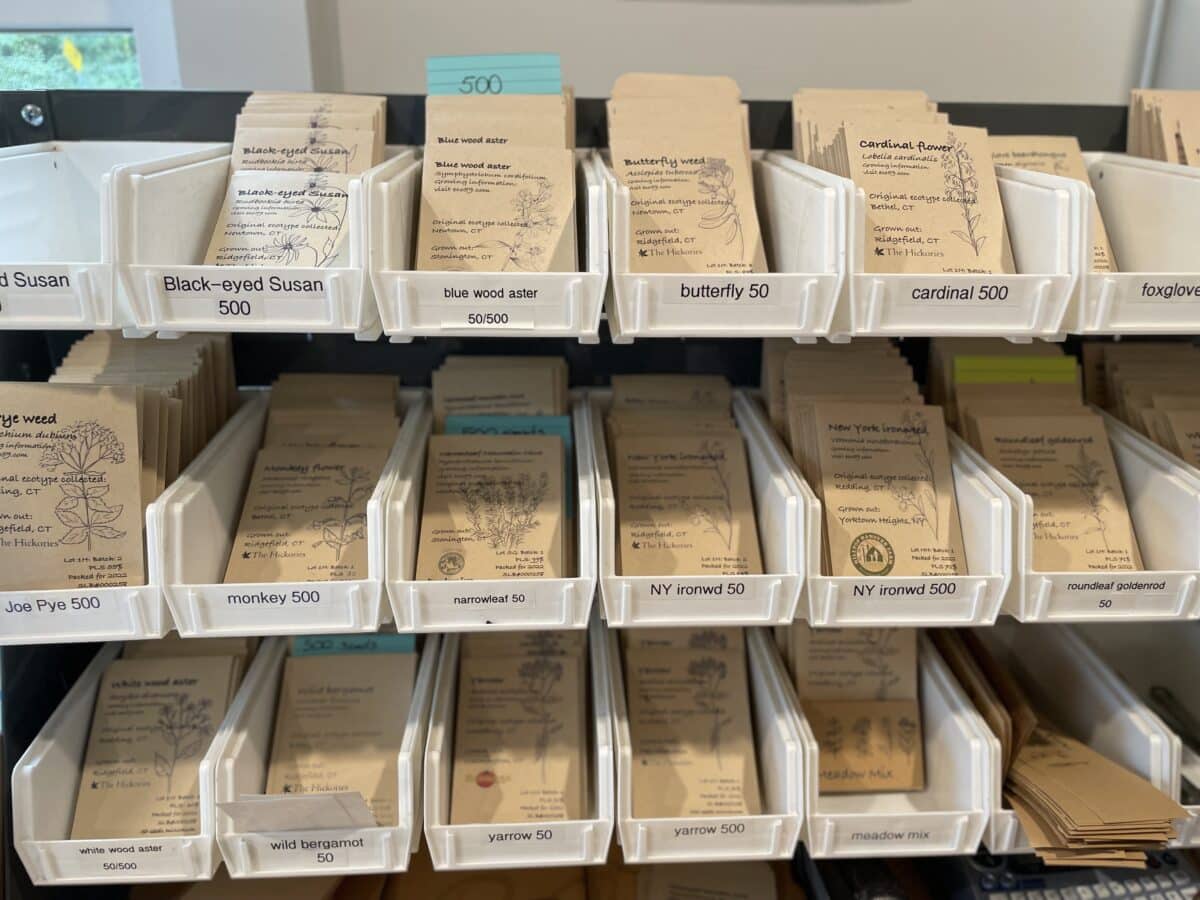

Packets of local ecotypic native seed, sold onsite and online at eco59.com. (Sefra Alexandra, the Seed Huntress)

In March 2023, the Ecological Health Network, Native Plant Trust and other partners launched the Northeast Seed Network. (Full disclosure: I serve on the Northeast Seed Network’s Steering Committee). The network’s central focus is to build and strengthen connections among a diverse web of social actors, including government agencies, Tribal Nations, educational institutions, nonprofit organizations, botanic gardens, farmers, private companies, citizen groups and academic institutions. By fostering collaboration among these stakeholders, the network aims to drive knowledge exchange, encourage impactful research and promote the adoption of best practices through building a community of practice. Network collaborators see this as a prerequisite to meeting the region’s restoration goals, reversing ecosystem degradation, advancing equity, generating farmer income and improving the health and well-being of both humans and wildlife.

Tailoring Seed Production to the U.S. Northeast

Dina Brewster, 47, founder of The Hickories farm in Ridgefield, Connecticut, produces seeds of native grasses and flowers on a certified USDA organic farm. As the director of eco59, a farmer-led seed-growing collective, and a member of the Northeast Seed Network’s steering committee, Brewster says that the secret to organic seed production is the concept of selection.

“Humans have carefully cultivated traditional crops like tomatoes, eggplants, and peppers for thousands of years,” says Brewster. “My planning for food crops is structured and predictable.” In contrast, Brewster explains, “native species used for habitat restoration exhibit unpredictability due to their natural adaptations, which enhances their survival.”

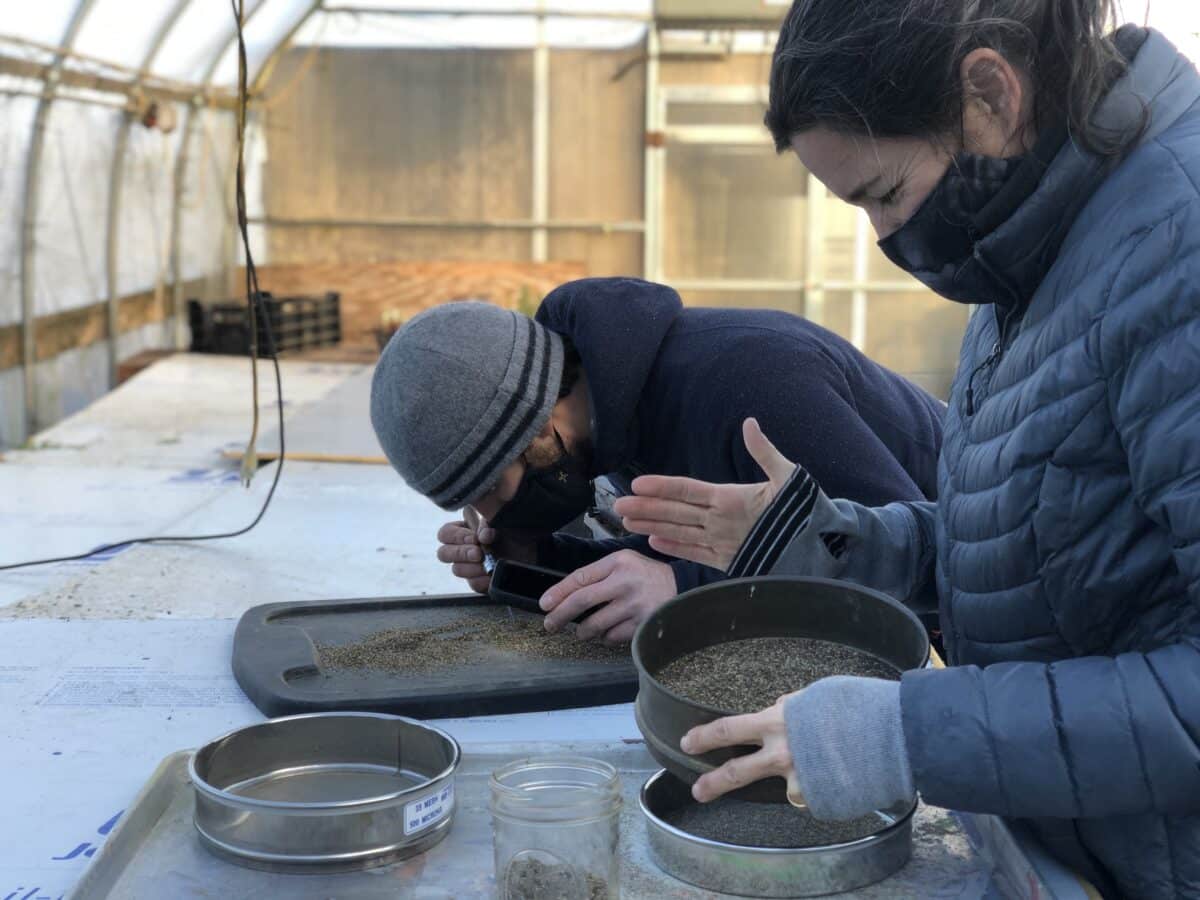

Dina Brewster and volunteer cleaning Mountain Mint (Pycnanthemum virginianum) seeds at the Hickories Farm. (Sefra Alexandra, the Seed Huntress)

Brewster explained how one season, she seeded an open flat tray with foxglove beardtongue (Penstemon digitalis), a native wildflower that attracts several species of bees and butterflies. After a few weeks of germination, only 75 of 300 seeds sprouted. She returned a few months later to find that another 75 plants had sprouted. A few months later, another 75 seeds sprouted. For Brewster, this shows the resilience of native plants and their ability to respond to variable environmental conditions.

Foxglove beardtongue (Penstemon digitalis), a native wildflower that attracts several species of bees and butterflies, going to seed. (Eve Allen)

Starting last year, Brewster has been trying to increase the seed supply of blue lobelia (Lobelia siphilitica), which attracts bumblebees, whose pollinating services are essential for growing crops like tomatoes and blueberries. At first, she noticed that when planted as a row crop blue lobelia seeds sometimes formed atypical blossom structures. However, she found that when they escaped into more natural and random settings they looked healthier and happier. “It’s puzzling because when we bring them into straight rows with well-fed soil, something changes,” Brewster says. “They’re trying to tell us that they prefer a different way of doing things.”

For Brewster, native seed farming requires embracing the inherent adaptive resilience of native plants. “It has been a rewarding journey, allowing me to see my role more as a caretaker of these plants rather than a traditional farmer,” she says. “While I acknowledge the value of organized planting and cultivation, I also sense there’s a different wisdom in these plants that we’ve yet to fully grasp.”

The role of small-scale organic farms

Native plants also have diverse applications that extend beyond ecosystem restoration. They play an indispensable role in fostering pollinator habitat, which is crucial for sustainable agriculture production and preserving biodiversity. Moreover, native vegetation is a linchpin in stabilizing and improving virtually every kind of landscape, from mitigating soil erosion along streams and riverbanks to enhancing the visual aesthetics of lands along roadways, while simultaneously helping achieve conservation goals.

In the domain of green infrastructure, native plants, thanks to their deep roots, offer cities and small towns an efficient means of stormwater management in structures like bioswales—the linear, shallow, vegetated features often near roadways or parking lots designed to control and treat surface water runoff. Native grasses are increasingly valuable in rangelands, serving as a crucial food source for grazing animals. Native species are also commonly used to strategically create vegetative fuel breaks to enhance fire safety.

Due to the unique growing patterns and practices of raising native seeds, small-scale organic farmers are an essential part of helping to scale up supply of important native species. Many of these farmers see it as a symbiotic effort, as growing native seeds can provide much-needed income.

“We have a distinctive chance to envision an economy centered around seed work that can bring about transformational changes for farmers,” says Brewster. “It’s essential to find ways to integrate seed work into restoration efforts and ascribe value to it. Following the path of low-cost, large-scale agriculture may lead us to underestimate the true value of seeds, ultimately diminishing their worth. This would be detrimental.”

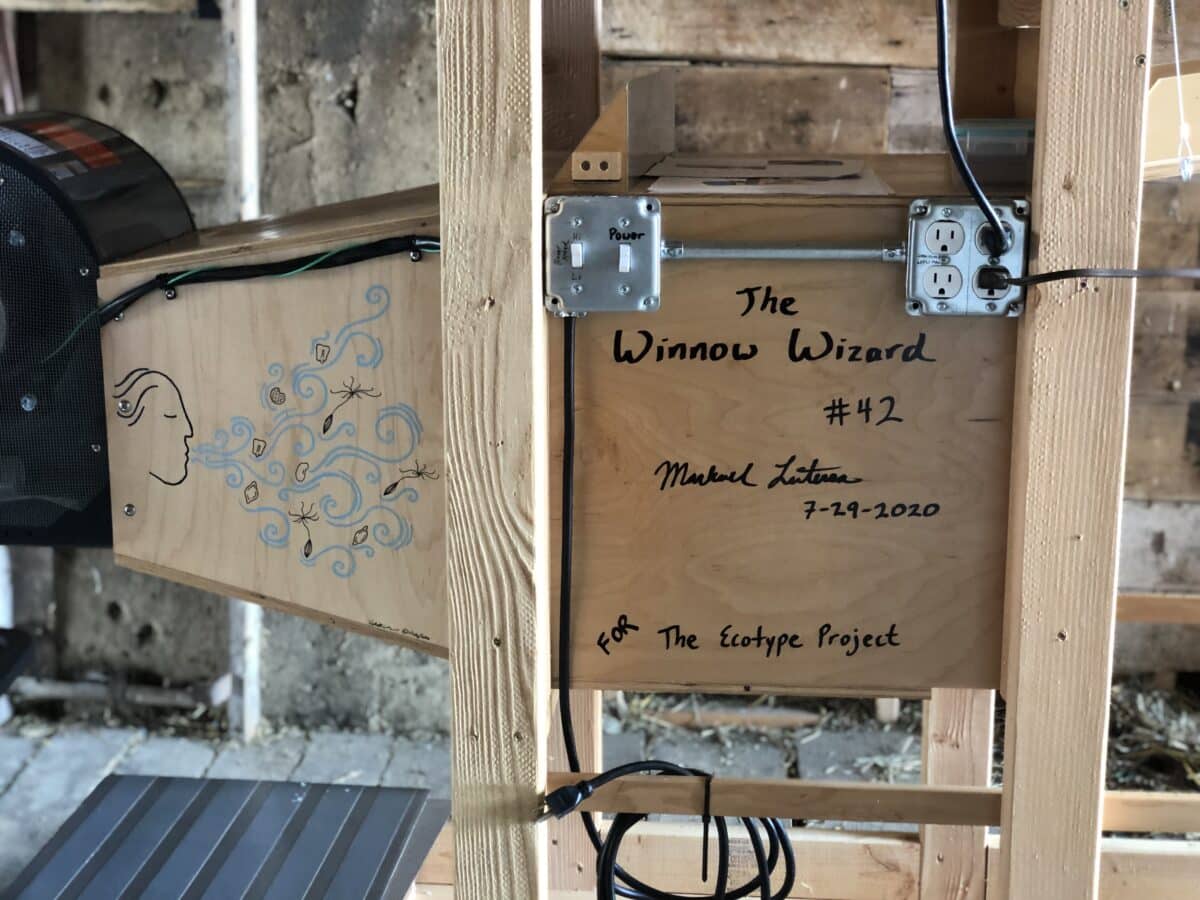

The Winnow Wizard is a custom-made machine developed for cleaning agricultural seeds that the eco59 seed-growing collective has adapted to clean native seeds. (Sefra Alexandra, the Seed Huntress)

Over the past 11 months, the Northeast Seed Network has diligently laid the foundation for enhancing collaborative capacity among partners to address key recommendations from the National Academies’ January 2023 report. For instance, 28 network members representing each supply chain step met regularly on Zoom for five months to create a Target Taxa list that will guide seed collection, storage and increase.

Northeast Seed Network partners also initiated a research project to gather more data on native seed demand and market segmentation. A comprehensive survey garnered over 300 responses from buyers and users of native seed and plant materials across thirteen states in the Northeast and Northern Mid-Atlantic regions of the United States. The insights gained from this research will be pivotal in informing strategic planning efforts in the upcoming year.

Brewster is hopeful that efforts like the Northeast Seed Network will build community in the broader region to collaborate, foster innovation and generate a supply chain model tailored to the region. She says, “The commitment and dedication of our partners and members is palpable and a rare and invaluable asset.”