American humorist and writer Mark Twain is believed to have once said, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it often rhymes.”

I’ve been working as a historian and complexity scientist for the better part of a decade, and I often think about this phrase as I follow different strands of the historical record and notice the same patterns over and over.

My background is in ancient history. As a young researcher, I tried to understand why the Roman Empire became so big and what ultimately led to its downfall. Then, during my doctoral studies, I met the evolutionary biologist turned historian Peter Turchin, and that meeting had a profound impact on my work.

I joined Turchin and a few others who were establishing a new field – a new way to investigate history. It was called cliodynamics after Clio, the ancient Greek muse of history, and dynamics, the study of how complex systems change over time. Cliodynamics marshals scientific and statistical tools to better understand the past.

The aim is to treat history as a “natural” science, using statistical methods, computational simulations and other tools adapted from evolutionary theory, physics and complexity science to understand why things happened the way that they did.

Mosaic representing the Greek muse Clio from the Severian period, coming from the villa located near the Baccano woods, and exhibited at the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme in Rome.

Jean-PolGRANDMONT/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY

By turning historical knowledge into scientific “data”, we can run analyses and test hypotheses about historical processes, just like any other science.

The databank of history

Since 2011, my colleagues and I have been compiling an enormous amount of information about the past and storing it in a unique collection called the Seshat: Global History Databank. Seshat involves the contribution of over 100 researchers from around the world.

We create structured, analysable information by surveying the huge amount of scholarship available about the past. For instance, we can record a society’s population as a number, or answer questions about whether something was present or absent. Like, did a society have professional bureaucrats? Or, did it maintain public irrigation works?

These questions get turned into numerical data – a present can become a “1” and absent a “0” – in a way that allows us to examine these data points with a host of analytical tools. Critically, we always combine this “hard” quantitative data with more qualitative descriptions, explaining why the answers were given, providing nuance and marking uncertainty when the research is unclear, and citing relevant published literature.

We’re focused on gathering as many examples of past crises as we can. These are periods of social unrest that often result in major devastation — things like famine, disease outbreaks, civil wars and even complete collapse.

Our goal is to find out what drove these societies into crisis, and then what factors seem to have determined whether people could course-correct to stave off devastation.

But why? Right now, we are living in an age of polycrisis – a state where social, political, economic, environmental and other systems are not only deeply interrelated, but nearly all of them are under strain or experiencing some kind of disaster or extreme upheaval.

Examples today include the lingering social and economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, volatility in global food and energy markets, wars, political instability, ideological extremism and climate change.

By looking back at past polycrises (and there were many) we can try and figure out which societies coped best.

Pouring through the historical record, we have started noticing some very important themes rhyming through history. Even major ecological disasters and unpredictable climates are nothing new.

Inequality and elite infighting

One of the most common patterns that has jumped out is how extreme inequality shows up in nearly every case of major crisis. When big gaps exist between the haves and have-nots, not just in material wealth but also access to positions of power, this breeds frustration, dissent and turmoil.

“Ages of discord”, as Turchin dubbed periods of great social unrest and violence, produce some of history’s most devastating events. This includes the US civil war of the 1860s, the early 20th-century Russian Revolution, and the Taiping rebellion against the Chinese Qing dynasty, often said to be the deadliest civil war in history.

All of these cases saw people become frustrated at extreme wealth inequality, along with lack of inclusion in the political process. Frustration bred anger, and eventually erupted into fighting that killed millions and affected many more.

For example, the 100 years of civil fighting that felled the Roman republic was propelled by widespread unrest and poverty. Different political camps were formed, took increasingly extreme positions, and came to vilify their opponents with progressively more intense language and vitriol. This animosity spilled over into the streets, where mobs of armed citizens got into huge brawls and even lynched a popular leader and reformer, Tiberius Gracchus.

‘Destruction’ from the The Course of Empire by Thomas Cole, 1836.

Wikipedia/ThomasCole

Eventually, this fighting spiralled into full-blown civil warfare with highly trained, well-organised armies meeting in pitched battles. The underlying tensions and inequalities weren’t addressed during all this fighting, though, so this process repeated itself from about the 130s BC until 14AD, when the republican form of government came crashing down.

Perhaps one of the most surprising things is that inequality seems to be just as corrosive for the elites themselves. This is because the accumulation of so much wealth and power leads to intense infighting between them, which ripples throughout society.

In the case of Rome, it was the wealthy and powerful senators and military leaders like Julius Caesar who seized on the anger of a disaffected populace and led the violence.

This pattern also appears at other moments, such as the hatred between southern landowners and northern industrialists in the run up to the US civil war and the struggles between the Tsarist rulers and Russia’s landed nobility during the late 1800s.

Meanwhile, the 1864 Taiping rebellion was instigated by well educated young men, frustrated at being unable to find prestigious positions in government after years of toiling away at their studies and passing the civil service exams.

What we see time and again is that wealthy and powerful people try to grab bigger shares of the pie to maintain their positions. Rich families become desperate to secure prestigious posts for their children, while those aspiring to join the ranks of the elite scratch and claw their way up. And typically, wealth is related to power, as elites try to secure top positions in political office.

All this competition leads to increasingly drastic measures, including breaking rules and social taboos to stay ahead of the game. And once the taboo of refraining from civil violence falls – as it too often does – the results are typically devastating.

Fighting for the top spot

These patterns probably sound familiar. Consider the college admissions scandal in the US in 2019. That scandal broke when a few well-known American celebrities were caught having bribed their children’s way into prestigious Ivy League universities like Stanford and Yale.

But it wasn’t only these celebrities who broke the rules trying to secure their children’s future. Dozens of parents were prosecuted for such bribes, and the investigations are still ongoing. This scandal provides a perfect illustration of what happens when elite competition gets out of hand.

In the UK, you could point to the honours system, which generally seems to reward key allies of those in charge. This was the case in 2023, when former prime minister Boris Johnson rewarded his inner circle with peerages and other prestigious honours. He wasn’t the first prime minister to do so, and he won’t be the last.

One of the really common historical patterns is that as people accumulate wealth, they generally seek to translate this into other types of “social power”: political office, positions at top firms, military or religious leadership. Really, whatever is valued most at that time in their specific society.

Donald Trump is only one recent and fairly extreme version of this motif that pops up time and again during ages of discord. And if something isn’t done to relieve the pressure of such competition then these frustrated elites can find masses of supporters.

Then the pressures continue to build, igniting anger and frustration within more and more people, until it requires some release, usually in the form of violent conflict.

Remember that intra-elite competition usually rises when inequality is high, so these are periods when large numbers are feeling frustrated, angry, and ready for a change – even if they have to fight and perhaps die for it, as it seemed some were when they stormed the US Capitol on January 6, 2021.

Put together, fiercely competitive elites alongside scores of poor and marginalised people create an extremely combustible situation.

When the state can’t ‘right the ship’

As inequality takes root and conflict among elites ramps up, it usually ends up hampering society’s ability to right the ship. This is because elites tend to capture the lion’s share of wealth, often at the expense of both the majority population and state institutions. This is a crucial aspect of rising inequality, today just as much as in the past.

So vital public goods and welfare programmes, like initiatives to provide food, housing or healthcare to those in need, become underfunded and eventually cease to work at all. This exacerbates the gap between the wealthy who can afford these services and the growing number who cannot.

My colleague, political scientist Jack Goldstone, came up with a theory to explain this in the early 1990s, called structural demographic theory. He took an in-depth look at the French Revolution, often seen as the archetypal popular revolt. Goldstone was able to show that a lot of the fighting and grievances were driven by frustrated elites, not only by the “masses”, as is the common understanding.

These elites were finding it harder and harder to get a seat at the table with the French royal court. Goldstone noted that the reason these tensions became so inflamed and exploded is because the state had been losing its grip on the country for decades due to mismanagement of resources and from all of the entrenched privileges that the elites were fighting so hard to retain.

‘Liberty Leading the People’ is a painting by Eugène Delacroix commemorating the July Revolution of 1830, which toppled King Charles X. Wikipedia

So just when a society most needs its leaders in government and the civil service to step up and turn the crisis around, it finds itself at its weakest point and is unfit for the challenge. This is one of the main reasons that so many historical crises turn into major catastrophes.

As my colleagues and I have pointed out, this is disturbingly similar to trends we are seeing in the US, the UK and Germany, for example. Years of deregulation and privatisation in the US, for instance, have rolled back many of the gains made during the postwar period and gutted a variety of public services.

Meanwhile in the UK, the National Health Service has been said to be “locked in a death spiral” due to years of cuts and underfunding.

All the while, the rich have got richer and the poor have got poorer. According to recent statistics the richest 10% of households now control over 75% of the total wealth in world.

Such stark inequality leads to the sort of tension and anger we see in all the cases mentioned above. But without adequate state capacity or support from elites and the general public alike, it is unlikely that these countries will have what it takes to make the sort of reforms that could decrease tension. This is why some commentators have even claimed a second US civil war is looming.

Our age of polycrisis

There is no doubt that we’re facing certain novel challenges today that people in the past did not. Not just in terms of the frequency and scale of ecological disasters, but also in the way that so many of our systems (global production, food and mineral supply chains, economic systems, the international political order) are more hopelessly entangled than they ever have been.

A shock to one of these systems almost inevitably reverberates into the others. The war in Ukraine, for example, has affected global food supply chains and the price of gas across the world.

Researchers at the Cascade Institute, some of the leading authorities working to understand and track our current polycrisis, present a truly terrifying (and not exahuastive) list of crises the world is facing today, including:

- the lingering health, social, and economic effects of COVID-19

- stagflation (a persistent combination of inflation and low growth)

- volatility in global food and energy markets

- geopolitical conflict

- political instability and civil unrest arising from economic insecurity

- ideological extremism

- political polarisation

- declining institutional legitimacy

- increasingly frequent and devastating weather events generated by climate heating

Each of these on its own would wreak significant devastation, but they all interact, each one propelling the others and offering no signs of relief.

There were polycrises in the past too

Many of the same sorts of threats occurred in the past too, perhaps not on the global scale we see today, but certainly on a regional or even trans-continental scale.

Even environmental threats have been a challenge that humans have had to deal with. There have been ice ages, decades-long droughts and famines, unpredictable weather and severe ecological shocks.

The “little ice age,”, a period of abnormally cold temperatures that lasted for centuries from the 14th to early 19th centuries, inflicted mass devastation in Europe and Asia. This poor climate regime caused a number of ecological disasters, including recurrent famine in many places.

During this period, there were major disruptions in economic activity exacerbating food insecurity in places reliant on trade to feed their populations. For example, Egypt experienced what academics now refer to as a “great crisis” in the late 14th century during Mamluk Sultanate rule, as a plague outbreak combined with local flooding that ruined domestic crops while conflict in east Asia disrupted trade into the region. This caused a major famine throughout Egypt and, eventually, an armed revolt including the assassination of the Mamluk sultan, An-Nasir Faraj.

There was also a notable rise in uprisings, protests, and conflicts throughout Europe and Asia under these harsh environmental conditions. And the bubonic plague broke out during this period, as the infection found a welcome home among the large numbers of people left hungry and cold in harsh conditions.

How different countries handled the pandemic

Looking at the historical data, one thing gives me hope. The same forces that conspire to leave societies vulnerable to catastrophe can also work the other way.

The COVID-19 outbreak is a good example. This was a devastating disease hitting nearly the entire globe. However, as my colleagues have pointed out, the impact from the disease was not the same in every country or even among different communities.

This was due to many factors including how quickly the disease was identified, the effectiveness of various public health measures, and the demographic make-up of countries (proportion of elderly and more vulnerable communities in the population, for example). Another major factor, not always recognised, was how social stressors had been building up in the years before the disease struck.

But in some countries, such as South Korea and New Zealand, inequality and the other pressures had been kept largely at bay. Trust in government and social cohesion was also generally higher. When the disease appeared, people in these countries were able to pull together and respond more effectively than elsewhere.

They quickly managed to implement an array of strategies to fight the disease, like masking and physical distancing guidelines, that were supported and followed by large numbers of people. And generally, there was a fairly swift response from leaders in these countries with the state providing financial support for missed work, organising food drives and setting up other crucial programmes to help people manage with all of the disruptions COVID brought.

In countries like the US and the UK, however, pressures like inequality and partisan conflict were already high and growing in the years before the first outbreak.

Large numbers of people in these places were impoverished and made particularly vulnerable to the disease, as political in-fighting left government response slow, communication poor, and often resulted in confusing and contradictory advice.

The countries that responded poorly just didn’t have the social cohesion and trust in leadership needed to effectively implement and manage strategies to manage the disease. So, instead of bringing people together, tensions were further inflamed and preexisting inequalities widened.

Sometimes societies do right the ship

These pressures have played out in similar ways in the past. Unfortunately, by far the most common outcome has been major devastation and destruction. Our current research catalogues almost 200 cases of past societies experiencing a period of high risk, what we call a “crisis situation”. Over half of these situations turn into civil war or major uprising, about 35% involve the assassination of a ruler, and almost 40% involve the society losing control over territory or completely collapsing.

But our research has also found examples where societies were able to stop political infighting, harness their collective energy and resources to boost resilience, and make positive adaptations in the face of crisis.

For instance, during a “plague” in ancient Athens (probably a typhoid or smallpox outbreak), officials helped organise quarantines and gave public support for medical services and food distribution. Even without our modern understanding of virology, they did what they could to get through a difficult time.

‘Plague in an Ancient City’, by Michael Sweerts (circa 1652) is believed to be referring to the plague of Athens. LACMA/wikemedia

We see also amazing feats of engineering and collective action taken by ancient societies to produce enough food for their growing populations. Look at the irrigation channels that kept the Egyptians fed for thousands of years during the time of the Pharaohs, or the terraced fields built high in the Andes mountains under the Inca empire.

The Qing and other imperial dynasties in China constructed a huge web of granaries throughout their vast territory, supported by public funds and managed by government officials. This required a massive amount of training, oversight, financial commitment and significant investment in infrastructure to produce and transport foodstuff all over the region.

These granaries played a major role in providing relief when harsh climate conditions such as major floods, droughts, locust invasions, or warfare, threatened the food supply. My colleagues and I have argued recently that the breakdown of this granary system in the 19th century — driven by corruption among the managers and the strain on state capacity — was in fact a major contributor in the collapse of the Qing, China’s final imperial dynasty.

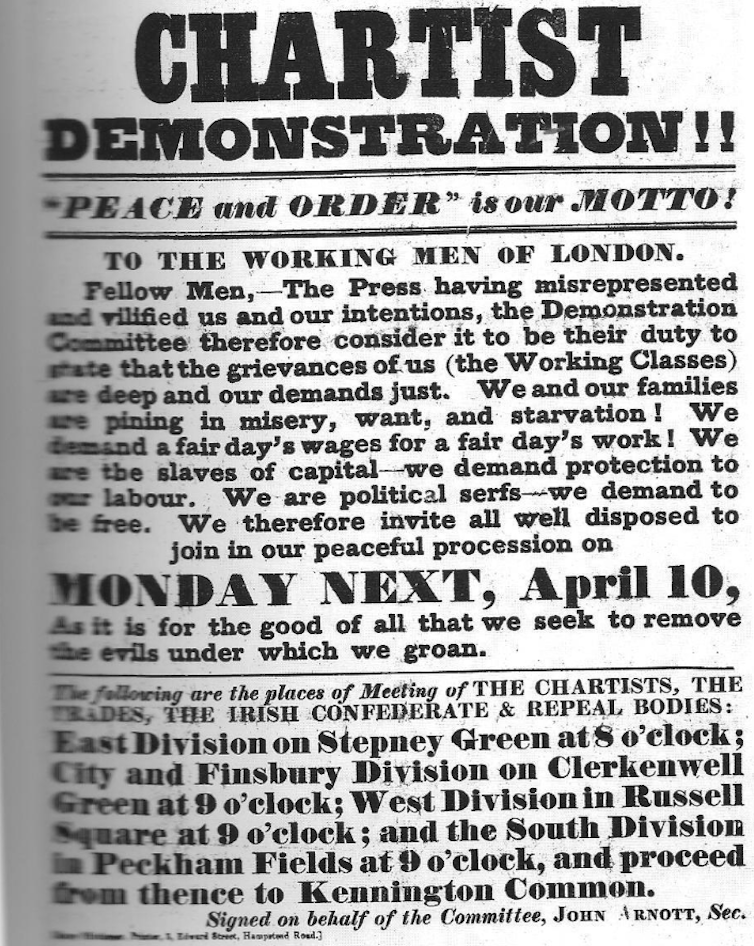

Elites in Chartist England

One of the most prominent examples of a country that faced crisis but managed to avoid the worst, is England during the 1830s and 1840s. This was the so-called Chartist period, a time of widespread unrest and revolt.

From the end of the 1700s, many of England’s farmers had seen profits diminish. On top of this, England was right in the middle of the industrial revolution, with rapidly swelling cities filling with factories. But conditions in these factories were atrocious. There was virtually no oversight or protections to ensure worker safety or to compensate anyone injured on the job, and employees were often forced to work long hours with minuscule pay.

The first few decades of the 1800s saw a number of revolts throughout England and Ireland, several of which became violent. Workers and farmers together charted their demands for more equitable and fair treatment in a series of pamphlets, which is where the period gets its name.

Many of England’s powerful political elite came to support these demands as well. Or at least there were enough to allow for the passing of some significant reforms, including regulations about worker safety, increased representation for the less wealthy, working class people in parliament, and the establishment of public welfare support for those unable to find work.

Poster advertising the ‘Monster’ Chartist Demonstration, held on April 10 1848. Rodney Mace, British Trade Union Posters: An Illustrated History.

The reforms resulted in marked improvement in the wellbeing of millions of people in the subsequent decades, which makes this a remarkable example. Although it needs to be noted that women were completely left out of the suffrage advances until years later. But many commentators point to this period as setting the stage for the modern welfare systems that those of us living in the developed world tend to take for granted. And crucially, the path to victory was made much easier, and considerably less bloody, by having elite support.

In most cases, where tensions mount and popular unrest explodes into violent protests, the wealthy and powerful tend to double down on maintaining their own privileges. But in Chartist England, a healthy contingent of progressive, “prosocial” elites were willing to sacrifice some of their own wealth, power, and privilege.

Finding hope

If the past teaches us anything, it is that trying to hold on to systems and policies that refuse to appropriately adapt and respond to changing circumstances — like climate change or growing unrest among a population – usually end in disaster. Those with the means and opportunity to enact change must do so, or at least to not stand in the way when reform is needed.

This last lesson is a particularly hard one to learn. Unfortunately, there are many signs around the world today that the mistakes of the past are being repeated, especially by our political leaders and those aspiring to hold power.

Just in the past few years, we have witnessed a pandemic, increasing ecological disasters, mass impoverishment, political gridlock, the return of authoritarian and xenophobic politics, and atrocious warfare.

This global polycrisis shows no signs of letting up. If nothing changes, we can expect these crises to worsen and spread to more places. We may discover — too late — that these are indeed “end times”, as Turchin has written.

But we also are in a unique position, because we know more about these forces of destruction and about how they played out in the past than ever before. This sentiment serves as the foundation for all of the work we have done compiling this massive amount of historical information.

Learning from history means that we have the ability to do something different. We can relieve the pressures that are creating violence and making society more fragile.

Our goal as cliodynamicists is to uncover patterns – not just to see how what we are doing today rhymes with the past – but to help find better ways forward.

![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.