I’m a millennial faculty member. The millennial generation – also known as Generation Y – came of age with 9/11, followed by the US-led wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, and then the 2007/8 financial crisis. While we were growing up, promises of perpetual progress and prosperity abounded. However, as we entered adulthood, we confronted the harmful realities and precarious nature of the prevailing social and economic system. It became clear to many of us that these were not only false promises but they also came at a high cost. Yet when we expressed our disillusionment, some from previous generations suggested our generation was the problem, not the system itself.

I have been able to connect with many of my students over this shared experience. My home academic department exclusively offers graduate programs, so for the first part of my career, most of my students were fairly close to me in age. For these students, my invitation to engage critically and self-reflexively with existing systems has been generally well-received. But last year, I taught my first undergraduate course, made up primarily of the generation that followed mine, Generation Z (“Gen Z”).

Most undergraduate students today are from Gen Z, and they will soon make up an increasing number of graduate students, too. Teaching Gen Z, just one generation removed from mine, was a learning curve. Issues of social and ecological justice that were important to me have an even deeper urgency for them. Initially, I did not fully appreciate the differences between their experiences and those of my generation, and because of this, it took me a while to gain their trust. I realized how easy it was to do to Gen Z students what others had done to my generation: minimize their concerns and fail to recognize the underlying reasons for their frustration, fear, and grief.

Facing difficult truths

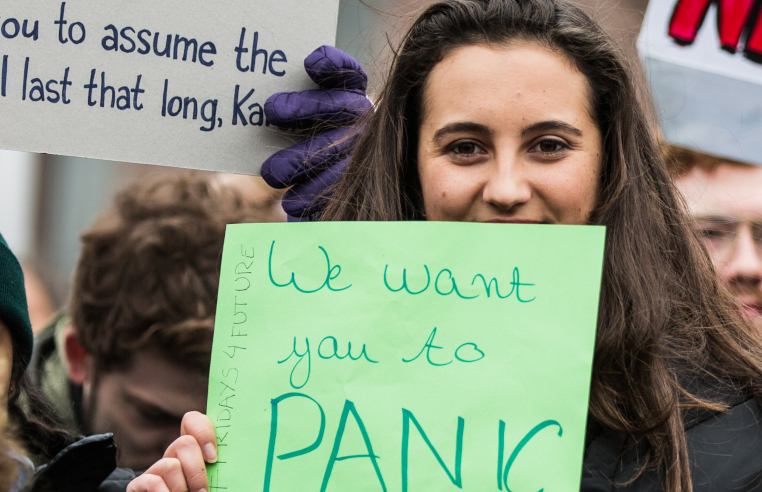

After centuries of people borrowing (some might say, stealing) from the future to pay for comforts in the present, the bill is coming due, and it is younger generations who will have to pick up the tab. In brief, this is because our finite Earth cannot sustain an economic system premised on infinite growth and consumption. Young people are acutely aware of this. In a recent survey of youth from 10 countries, 75% said they think the future is frightening and 83% said people have failed to take care of the planet.

As a result, many young people are asking us to see what we would rather not see, to turn toward things as they are, rather than as we would like them to be. They are asking us to admit to ourselves what they cannot deny: that escalating wars, economic inequality, extreme weather, biodiversity loss, food insecurity, and mental health crises are a product of our existing system; that the problems created by this system cannot be addressed using only the tools created by the system itself; and that there is a very real possibility of social and ecological collapse within their lifetimes, if not ours.

This is not something most faculty are generally interested in hearing. While some parts of us may be aware that things cannot continue as they are, our other, less mature parts tend to deny the potential for collapse because we fear being overwhelmed and immobilized by the depth and magnitude of the problem. That is an understandable fear, but it is not a legitimate justification for denial. To ignore these concerns is not only a mistake but also a refusal of our responsibilities as educators, and as human beings.

Accepting the stark realities of our collective predicament is not just about confronting the unsustainability of our current system. It is also about un-numbing to the pain that comes with possible systemic collapse, as well as to the pain that has already been created by this system. This includes the pain we ourselves have caused, given that centuries of economic growth in the Global North have been directly enabled by exploitation, extraction, and expropriation in the Global South, and in Indigenous communities around the world. In this way, at the same time as we accept the possibility of systemic collapse, we would need to also accept responsibility for many collapses that have already happened – the ecocides, genocides, and epistemicides – so that the beneficiaries of the current system could enjoy ever-expanding comforts and securities.

The education of older generations, including my own, has not prepared most faculty to hold these harsh truths and process these heavy emotions in generative ways, and thus, the education we offer our students is not preparing them to do so either. However, many students are seeking this kind of support. Thus, it is no surprise when they question the relevance of the education they are currently receiving. Effectively, we are educating people to “refine a system that operates by undermining the conditions of possibility for our biophysical survival.” As one student put it,

“Should we even be wasting these last fleeting years of our youth in a classroom when our elected leaders are leading us down a path toward total climate collapse?”

This is not just about the content we include in our courses, but also whether we make space in classrooms and campuses for students to pose challenging and uncomfortable questions. Recently, we have seen a rise in the suppression of students’ academic freedom. In response, a student in one of my courses observed,

“While education should be a realm of openness and exploration, the current situation suggests the opposite, creating uncertainty about where I stand in this educational equation.”

Holding space for unanswerable questions

We do not have to agree with everything our students say or believe in order to create educational spaces in which they can ask difficult questions of us, themselves, and the world around them. In my experience, the most important thing for many students is not that we agree with them, but that we be brave enough to walk alongside them as they meet the many unknowns and unknowables of the current moment. However, this request is not necessarily welcomed by those of us who were socialized to expect comfort, security, certainty, and the affirmation of our intelligence and relevance.

Thus, to collectively navigate current and coming challenges with our students, faculty would need to deepen our capacity to hold what is complex, heavy, uncertain, and uncomfortable. We would also need to develop the stamina to continue this work when it feels easier to just enjoy the excesses of the current system for as long as they last. And we would need to accept responsibility for unpaid intergenerational debts, but also the debts that are owed by the Global North to the Global South, and by settlers to Indigenous Peoples. When discussions about these responsibilities arise, many of us focus on what we stand to lose. But what might we gain if instead, we accepted young people’s invitation for us to grow up and face our complicity in harm?

Last fall, I attended a conference and was asked to present on a panel with fellow Gen Y scholars. The discussant, a professor from Gen W (the generation born in the years following World War II), noted with gratitude that they felt genuinely challenged by our papers. In their closing remarks, they encouraged us to respond with the same level of compassion and humility when the next generation of scholars inevitably challenges us: to welcome not just new ideas, but also the general spirit that it is possible, and often necessary, to do things differently than we have done.

This professor’s example of academic “eldership” gave me a glimpse of how intergenerational relationships in the academy could be otherwise – more generous, self-reflexive, and accountable. It would not be easy, but it is possible to create the conditions in which we can have difficult conversations without relationships falling apart. If we can learn to do this, we will likely be better prepared to coordinate responses to complex challenges in ways that prioritize the well-being of current and coming generations of human and other-than-human beings. Systemic violence and ecological catastrophe did not begin with my generation, nor with any of the generations that are alive today. But we have a responsibility to make different choices than those that came before us, rather than continuing to pursue the same perceived entitlements.

Stepping back and showing up

I do not romanticize younger generations, believe they have “the answers”, or place all hope for the future in their hands. Doing so would be naive of me, and unfair to them – a deflection of my own and other generations’ responsibility for engaging in the tough work ahead. We are all part of the problem, and we are all still learning.

None of us know exactly what to do in this liminal space between a system in decline and whatever comes next. But we each have a small role to play as we figure it out and we have much to learn from each other in the process. This may be uncomfortable for professors who have crafted not only our professional identities but also in many cases our self-images around being the ones with “the answers.” Thus, we would need to lose our academic arrogance by stepping back from familiar patterns and showing up instead with humility as the full, flawed people that we are if we want to do the intergenerational relationship-building that is needed in this transitional moment.

This includes holding space for young people to process their fears, grief, insecurities, and traumas. Older generations would need to process our own as well and to share the insights from that processing with younger generations. Together, we might collectively learn from the mistakes of the existing system so that we do not repeat them, discern what from that system should be preserved and what needs to be “composted,” and develop a practice of ongoing collective experimentation with emerging possibilities that will inevitably lead to new mistakes but also new learning.

If all generations could commit to this work, together we might have a chance of interrupting the cycle of irresponsibility and immaturity that led us to this crisis point in the first place, and enabling something different and possibly wiser to emerge. Although faculty are not required to do this work as part of our formal job responsibilities, current and future generations will pay the price if we don’t. We owe each other more than that.