The economy of the rich world is a massive, geological force—it plows onward with glacial power, pushing through obstacles like global pandemics; if it stalls, it’s usually only momentarily before it picks up speed again. Or perhaps to use a better, internal-combustion-era metaphor, it’s a speeding tractor-trailer on a downhill run, barely able to brake even if it wanted to.

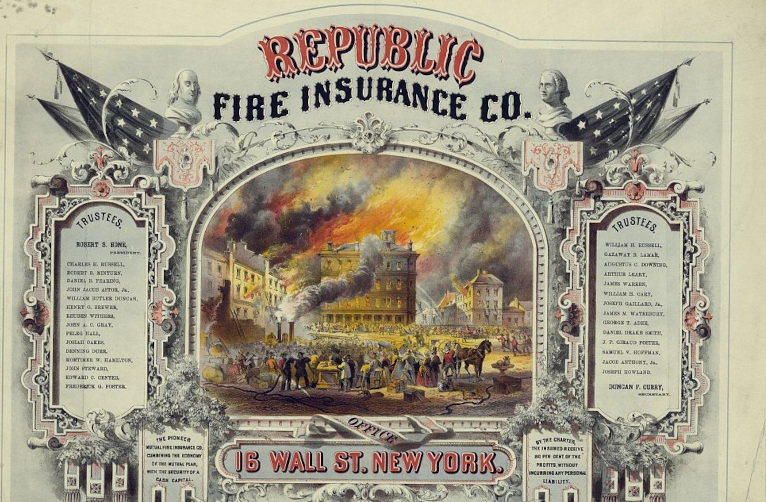

But I think we’re very near the point where—thanks to the climate crisis—the economy encounters sufficient friction to slow it, and maybe even to send it in a careening spin. Last week the Wall Street Journal (whose news columns are as useful as their editorial pages are obtuse) published a long piece of reporting with a stark headline: “Buying Home and Auto Insurance Is Becoming Impossible.”

The essay began by describing the way that Allstate—after suffering billions of dollars in losses last year—threatened to stop writing policies in New York, New Jersey, and California. Regulators in all three states, terrified of that possibility, let them raise rates by preposterous amounts

In December, New Jersey approved auto rate increases for Allstate averaging 17%, and New York, a 15% hike. Regulators in California are allowing Allstate to boost auto rates by 30%, but still haven’t decided on its request for a 40% increase in home-insurance rates after the insurer refused to write new policies.

The Journal was entirely clear about the reasons:

The past decade of global natural catastrophes has been the costliest ever. Warmer temperatures have made storms worse and contributed to droughts that have elevated wildfire risk. Too many new homes were built in areas at risk of fire.

And it was entirely clear about the likely consequences:

“Climate change will destabilize the global insurance industry,” research firm Forrester Research predicted in a fall report. Increasingly extreme weather will make it harder for insurance companies to model and predict exposures, accurately calculate reserves, offer coverage and pay claims, the report said. As a result, Forrester forecast, “more insurers will leave markets besides the high-stakes states like California, Florida, and Louisiana.”

Allstate CEO Wilson said: “There will be insurance deserts.”

Insurance deserts, where private-sector companies no longer will sell regular home-insurance policies, are already developing in high-risk areas. Florida’s insurer of last resort is now the main provider of home coverage in that state.

As I read all this, I flashed back to a 2005 study I’d written about at the time. Swiss Re, one of the world’s biggest reinsurance firms, had hired a team from Harvard to model the effects of increased climatic upeheaval. It found that as storms and other disruptions become more frequent, they “overwhelm the adaptive capacities of even developed nations; large areas and sectors become uninsurable; major investments collapse; and markets crash.” Pay careful attention, despite the bland phraseology:

In effect, parts of developed countries would experience developing nations conditions for prolonged periods as a result of natural catastrophes and increasing vulnerability due to the abbreviated return times of extreme events.

“Abbreviated return times of extreme events” is a bland enough phrase, sort of like “objects in mirror may be closer than they appear,” but it is a pretty good caption for our moment: here where I live in Vermont (which is sometimes thought of as a ‘cliamte refuge’), we’re dealing with floods and storms at a rapidly increasing rate—a spokemsan for our local utility said last fall that “our three worst storms were last year.”

Homeowners unable to get affordable insurance is a problem in and of itself, but what it really presages is what the Harvard team described: a drag on the economy that eventually causes real change. Insurance sounds like a boring topic, until you think about it a little: it’s the (enormous) part of the economy that’s assigned to understand risk. And to do so it developed one of the most powerful technologies in all of human history: the actuarial table. Using it, the industry can predict what’s going to happen—predict it accurately enough to allow everyone else to affordably hedge against that risk. Without that hedge, investment—in a house or a company—becomes almost impossible. Climate change is wrecking that tool, because an actuarial table depends for its power on the world behaving more or less as it has in the past. As the Journal put it, succintly,

“climate change has made it harder for insurers to measure their risks, pushing some to demand even higher premiums to cushion against future losses.”

Don’t cry for insurance companies. Not only do they figure out how to charge higher premiums, they’ve also helped create this crisis: with the biggest pool of investment capital on the planet, they’ve continually helped fund the expansion of fossil fuels, and these same companies continue to underwrite the pipeline projects and LNG export terminals that are doing them in. (“When it comes time to hang the capitalists, they will vie with each other for the rope contract,” Vladimir Ilyich Lenin may or may not have said).

And perhaps we shouldn’t even cry for our own selves—insurance, after all, is a luxury available mainly to people in those places that have driven the climate crisis. Most of the world has been dealing with it without any help, a fact we were reminded of this week when a UN report delivered the staggering news that a quarter of our fellow humans—the vast majority in poor countries—were currently dealing with drought.

“Droughts operate in silence, often going unnoticed and failing to provoke an immediate public and political response,” wrote Ibrahim Thiaw, head of the United Nations agency that issued the estimates late last year, in his foreword to the report.

The many droughts around the world come at a time of record-high global temperatures and rising food-price inflation, as the Russian invasion of Ukraine, involving two countries that are major producers of wheat, has thrown global food supply chains into turmoil, punishing the world’s poorest people.

I think even the powers that be are starting to recognize our peril—Sourcing Journal, (“the largest, most comprehensive and authoritative B2B resource for executives working in the apparel, textile, home and footwear industries”) warned last week that “extreme weather” was now the greatest threat to supply chains. (You read about attacks on ships in the Red Sea, but the big story in logistics right now is the drought that’s so lowered the water level in the Panama Canal that shippers have to send their cargoes on rail across the isthmus). And as the world’s leaders jet into Davos this week, the World Economic Forum has decided that even amidst AI and war, climate presents the greatest risk to our prosperity.

In the long term — defined as 10 years — extreme weather was described as the No. 1 threat, followed by four other environmental-related risks: critical change to Earth systems; biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse; and natural resource shortages.

(Note, by the way, that ‘long term’ is defined as the next decade, which should tell you something about how we got into this trouble in the first place).

To return to our metaphor, the enormous momentum of the global economy is beginning to run into the enormous friction of climate change. If we were all working with good faith to build systems that could absorb the shock, we’d have a chance. But at the moment the fossil fuel industry is—internal combustion metaphor again—pushing the pedal to the floor. Its response to the hottest year in the last 125,000? An eight-figure ad campaign launched last week “promoting the idea that fossil fuels are “vital” to global energy security.”

So on we fight.