The nitrogen drama in the Netherlands shows how the industrial model of farming is corrupt and that a recoupling of ecology and economy is required.

In the Netherlands, the government has put pressure on the farm sector to reduce the emissions of reactive nitrogen (ammonia, laughing gas) from animals. The government is in turn pressured by the EU Commission. In 2019, European Union’s top court and the Dutch Council of State, the country’s highest administrative court and legislative advisory body, ruled that the Netherlands had breached EU environmental standards by failing to ensure they were met in 162 protected nature areas.

The government aims to reduce nitrogen emissions by 50% by 2030, and by 75% in protected nature reserves (Natura 2000 areas). Initially there will be voluntary buy-outs of farms, but in the end, forced closures can take place if voluntary measures don’t yield the desired results. In the end of 2023, some 750 farms have signed up for the buy-out scheme.

Farmers have protested since 2019 and the conflict even resulted in the formation of a new political party, BoerBurgerBeweging (Farmer-Citizen Movement). In the provincial elections 2023 it was the biggest party with 19.3% of the votes. In the general election 2023 they got 4.6% of the votes.

In many countries farmers have expressed their solidarity with Dutch farmers. But too often there has been huge misunderstandings for why and how this happened. Some spout the idea that farms will be closed down to provide space for immigrants – something that is totally baseless. Obviously, it is hard for a farmer that has invested his/her life in farming to hear that they have to close down. But there are legitimate reasons to reduce livestock farming in the Netherlands.

The Netherlands is the number two food exporter (just the US is bigger) in the world, quite astonishing for such a small country. But it is equally a very big importer with place four after China, US and Germany. The Dutch are not only good at farming but also at food industries and trade. Importing raw materials and converting them to higher value products is one of their specialties. That is done in factories but it is also done in livestock farms. And industrial livestock farming and industrial food processing have many linkages.

The Netherlands produces a lot of animal feed as a by-product from the processing of oil seeds such as soy, sunflower and rape seed. Around 4 million tons of soybeans are imported to the Netherlands each year, one third of EU total imports. The soy is turned into soy oil for the food industry and soy meal for the livestock industry. Together with direct imports of animal feeds, the number of livestock, in particular monogastric (chicken and pigs), if far above what the land can sustain. The net result is nutrient overload in the farms. The Netherlands has the highest density of livestock in Europe measured in livestock units per agriculture land, 3.2 livestock units per hectare, far above what the land and the environment can sustain.

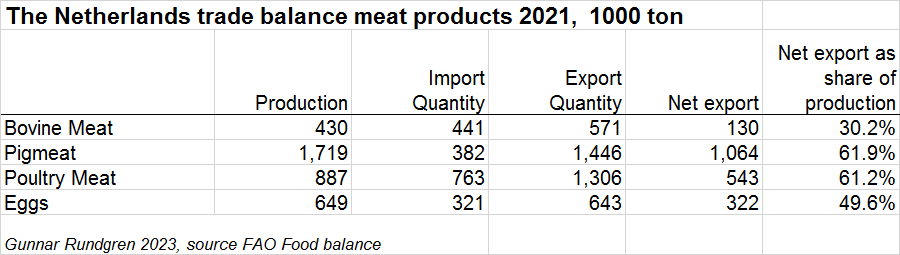

Net exports (i.e. the exports minus imports) of pig meat amounted to more than 1 million ton 2021 and exports of poultry and eggs were also big (see table). The Netherlands is also a big exporter and importer of dairy products. I don’t show any figures of the dairy trade as most people will just be confused by the plethora of dairy products traded and terms such as milk equivalents.

The country doesn’t only export huge quantities of livestock products but also manure. In 2020, exports reached more than 3 million tons, more than 200 kg per person living in the country. Despite the huge exports, there is a nitrogen overload in the country.

A bit of historical background may be warranted: Dutch farmers are incredibly skilled and productive and have been for a long time. Even if England often get the credit for the first European Agriculture revolution, it actually started in the Low Countries. The early success of Dutch farming, together with the colonial bounty paved the way for the prominent role of the Netherlands in world trade. Ironically, while the farmers were proto-capitalists, the industrial revolution turned them back into family farms:

“Transforming beets into sugar and raw milk into cheese and butter shifted from farms to factories, turning the farmer eventually into a producer of commodities instead of the end products he was used to make and sell profitably. “

Today, the traders and food processors in the Netherlands has since long freed themselves from the dependence of Dutch farmers and simply don’t need them anymore, which clearly weakens their position.

That the Netherlands is heavily populated and land prices are exorbitant also weakens the position of farmers. Urban sprawl in the most populated province, South Holland, forced greenhouses to relocate to other parts of the country. Farmers were already relocating to other countries before the new rules, but this is likely to pick up speed even more.

In a way it is strange that farmers in Sweden and other countries support their Dutch farming colleagues’ protests. The model and scale of industrial livestock production in the Netherlands is simply not sustainable. But I guess it is a case of esprit de corps. But it is equally strange that there are huge protests when environmental legislation leads to farm closures, but there are, rarely, protests among farmers against the fact that big farms outcompete small farms leading to a rapid reduction in the number of farmers. Between 1950 and 2016 six out of seven farms have been lost in the Netherlands, not as a result of draconian environmental regulations but as a result of the supposedly benevolent invisible hand of the Market. Their house is often sold as holiday house to city people and the land is picked up by industrializing neighbor farmers. In 1950, a pig farmer had 7 pigs – the average is 1600 pigs per farm.

The situation in the Netherlands is not unique. Also on Belgium, Denmark and Germany are measures taken to reduce livestock production. Pork production in Germany has decreased with 10% 2023 compared to 2021. For a long period pork production in Spain has increased steadily, but now also Spain is reached by tougher environmental and animal welfare legislation. In addition, rural populations have discovered that big pig farms are not creating many jobs but a lot of nuisance.

It is not surprising that farming, and in particular livestock factories in densely populated regions, is questioned. Pigs, hens and cows were driven out of European cities some hundred years ago and are now driven out of many cities in developing countries. Market gardens have gradually resettled from peri-urban areas to less populated areas. With urban sprawl and gentrification of the country side, priorities and economic powers are flipping against farmers. Through the industrialization and globalization of farming in general, and livestock production in particular, farmers have also weakened the relationship with consumers and citizens alike. It should not come as a surprise that citizens see very little value in supporting an export sector that destroys the environment and treat the living animals as production units. It is as popular as dogs shitting in a city park.

One could wish that this development would open up for a renaissance for small scale farming, including livestock production. But the land prices are in most cases far too high and competition too stiff to make any commercial small-scale farming viable. It seems to me that if farming is to survive in those densely populated areas it will be as a public good, or a commons, similar to parks and nature reserves. Perhaps along the lines of Parc Agrari de Baix Llobregat, the agriculture park of Barcelona. But that assumes that it is made in a way conducive to the environment and that the public, one way or the other, takes responsibility for the viability of farming.

In the longer term, agriculture and food systems must be organized in a similar way as natural ecosystems where most, but not all, nutrients are circulating within the ecosystem.*

Industrial agriculture systems are based on linear flows of nutrients where huge quantities of nitrogen, phosphorus and potash is brought in and equally huge quantities of agriculture commodities are sold out of the system, increasingly in global markets. Losses are very high already in crop production, they increase in livestock production and in the consumption stage almost all nitrogen is lost. The losses, in turn, constitute pollution. According to the planetary boundaries framework, nitrogen and phosphorus overload is one of the areas for which the safe boundary has been transgressed the most. The fact that excess nitrogen in agriculture also harms ecosystems far away from the actual use also points to yet another flaw in the argument that one can “spare” nature by intensifying farming.

According to the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment, annual (average 2012 to 2014) inputs of nitrogen in Dutch agriculture amount to 639 million kg, in the form of animal feed not produced on the farms (404 million kg), artificial fertiliser (194 million kg) and other products, and via atmospheric deposition. Nitrogen in animal and plant-based agricultural products and disposal of manure outside agriculture amount to 367 million kg. The difference of 272 million kg partly disappears into the ground (185 million kg) and partly into the air (87 million kg). But ultimately, almost all of the remaining 367 million kg brought out of agriculture will also be lost in the consumption phase, either in the Netherlands or abroad. Since the large scale introduction of the water closet (flush toilet), most nutrients and in particular all nitrogen is simply flushed out. The sewage sludge will contain a considerable share of the phosphorus, but the sludge is often contaminated and should therefore not be recycled into crop production.

The case for a local food system is thus not only based on the economic and social effects of the working of the global food system but it is also based on fundamental ecological principles. Researchers at the Wagening university demonstrate that if the Netherlands were to stop importing animal feed and “recouple” livestock numbers and domestic feed production, livestock numbers would be dramatically reduced. Emissions of ammonia and greenhouse gases would be in line with the national emission targets while the amount of livestock products would still cover the current consumption of the population.

Their research didn’t go one step further into scenarios where artificial fertilizers were also excluded. By and large, such a step would require a redesign of the blackwater systems, compost toilets etc. It would also have huge impacts on the design of agro-ecosystems and lead to better crop rotations, increased acreage of leguminous plants, a recoupling of crops and livestock on farm level, less monogastric animals but maintained or even increased numbers of ruminants fed on grass. A recoupling of human diets to the local conditions and substantially reduced food waste would also be demanded. I have expanded on this in the article The nitrogen challenge for organic agriculture.

By and large it is about recoupling ecology and economy. It is possible, it is desirable and it is ultimately inevitable as there can be no sustainable economy without a sustainable ecology. But it can’t be realized within a global, industrial and capitalist framework for food and agriculture.

* Even natural ecosystems will exchange a smaller fraction of nutrients with surrounding ecosystems. Nutrients are brought into the system by dust and rain as well as living animals (e.g. birds move a lot of nutrients from the sea and lakes to land) and biological nitrogen fixation. Weathering of rocks and minerals in soil also make new nutrients available. Meanwhile nutrients are lost by leaching, erosion and moving animals.