Most people are probably familiar with text substitution, in some form. It’s when a particular bit of text in a document is replaced throughout with an alternate. In many packages this is carried out via a Find/Replace dialog box. My main use has been in a Unix/vi environment, where the friendly and intuitive command

:1,$s/old text/new text/g

finds every instance of “old text” and replaces with “new text.” The true nerd will appreciate that the command is compatible with ‘regular expressions’ (an innocent-looking term that conceals a boatload of nerdcrap).

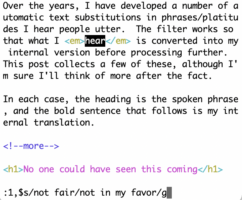

Over the years, I have developed a number of automatic text substitutions for phrases/platitudes I hear people utter. The filter works so that what I hear is converted into my internal version before processing further. This post collects a few such examples, although I’m sure I’ll think of more after the fact.

In each of the cases below, the heading is the spoken phrase, and the bold sentence that follows is my internal translation.

No one could have seen this coming

I didn’t see this coming (or denied the possibility). This is almost always said as a CYA (cover your @$$) admission of failure. Of course some people saw it coming. With 8 billion pairs of eyes on the world, hardly anything is completely out of the blue. Whether a financial crisis, war, peak oil, a pandemic, or any number of other calamities, it is not difficult to find credible warnings of exactly that threat. Naturally, not all warnings hit the mark, but real, materialized problems almost always had detailed and legitimate warnings. Bursting financial bubbles are a good example: a lot of smart (and lucky) people get out in time, while the rest “can’t see it coming.”

I need some protein

I want some tasty meat. And the related question from a server: “what protein would you like with that” is simply “what meat do you want today?” Two things are going on here. One is protein excess: Americans eat far more protein than is necessary for health. Vegetarians are familiar with the reaction of horror: “how is it you manage not to die on a daily basis?” Yet somehow more than a billion people live full, healthy lives without even paying explicit attention to protein intake. The other factor is a “whitewashing” of the the increasingly problematic word “meat.” But this is on balance a good thing. As a parallel, racism still has a foothold in America, but at least everybody got the memo that being racist is shameful. Racists will hilariously sputter and reject that label, which is a simultaneously humorous and depressing form of progress. Likewise, the sense that meat is an overindulged luxury that has outsized environmental costs is starting to weigh on people, so the word “protein” offers temporary feel-good cover. I can still find it annoying, though. Own up to your meat cravings, people!

If you build it, they will come

Faith is all you need! Sometimes things work out. But it does not take much effort to see entrepreneurial failures all around also. I often wonder how many people have driven themselves to ruin in a risky venture buoyed by this mantra. It relates to a phrase I do like: Never up; never in. The context is golf, which I swore off as a teenager. An anemic putt has no chance of falling in the hole, so at least put in enough effort to permit (not guarantee) success. So it’s true that if you don’t build it, no one will come. It’s just that “building it” may also be disastrous. I muse about alternate endings: If you build it, that’s on you. Or: good luck with that.

They’ll think of something

I have no idea how the world works, but take comfort in thinking I’ll be looked after by people smarter than me. It’s almost adorable, if not a little disconcerting that real challenges get brushed aside in such a way. To be fair, this attitude rests on a long track record of technological achievement. But the books are far from balanced: the number of global problems we have created (now tangled into an outright predicament) far exceeds the number of global problems we have solved and put behind us. So while I appreciate the appeal of the sentiment, I’m not buying it. Oh, and I think I may be a member of the “they” club, by the way, which makes it even less reassuring to me.

Necessity is the mother of invention

I have faith that any need will be met, because it’s a need. This one is very similar to the last one, but I want to take another swing at exposing the lie. By today’s standards, most of human history would be considered a period of extreme necessity—lacking modern conveniences. Yet most of this period had very little invention. Likewise, consider where in the world most invention happens. Is it in developing countries where necessity is greatest, or in powerhouse nations like the U.S. (or coal-rich Europe during the Industrial Revolution)? A person on the edge of starvation is overflowing with necessity, but unlikely to invent their way out of the problem. So the phrase, soothing as it may be to our fragile sensibilities, is obviously a gross distortion. Sure, inventions often react to a need, but really opportunity and resources are far more important. The innovation explosion of the modern age was not born of necessity, which had been ever-present, but of fossil fuels. Maybe necessity is the father of invention: supplying the seed (rhymes with need, so I think I’m onto something), while resources and opportunity are the mother that nurtures and brings the idea to fruition. Most seeds fail to produce any result.

Individual action is an ineffective drop in the bucket

I don’t want to give up any comforts, thank you very much. I get the fact that we are stuck in modernity, and that individuals don’t control the whole shooting match. But lots of things are under an individual’s control—like thermostat settings, dietary choices, air travel, vacations, consumer activity, shower frequency/duration, etc. The excuse that one person’s “sacrifices” won’t change anything borders on offensive to me, as it acts to effect a willful self-fulfillment of the “no change” prediction. Obviously, if many people engaged in trimming their impact, the net effect could be rather significant (why is that so hard to get?). Similarly, an individual’s vote is a drop in the bucket that seldom drives an election’s outcome. But collectively, each vote is everything. Without them, the whole scheme would fail. So, justified or not, this is what I “hear” when someone says such a thing: “I can’t be bothered.” I think it reflects a defensive, guilty psychology. It’s a counter-attack meant to deflect attention from their lack of willingness to take some responsibility. One could almost take pity.

That’s not fair

That does not appear to work in my favor. Seldom will a kid eating ice cream notice the hungry stranger and protest about fairness. Uniform enactment of a policy might appear to penalize some and reward others. I saw this all the time in the context of grades or requests for exceptions by students. In principle, everyone may be held to the exact same standard (definition of fair), but those who don’t get what they want are far more apt to charge unfairness. Sometimes in response to “that’s not fair,” you’ll hear: “life’s not fair,” which is getting at a core truth The physical universe will do what it does, indifferent to our notions of fairness. One tree might get taken out by a landslide, while the one next to it survives. Fairness doesn’t come into it. Lots of things could be called “unfair,” and that’s actually okay/normal. The conceit that we can control the world to the extent that unfairness or differential experience is eradicated is yet another manifestation of human exceptionalism.

I have rights, you know

I want it my way, and you’re getting in the way of that. The is the adult version of “that’s not fair.” It tends to be a winner, like touching “base” when playing tag: you can’t touch me if I use the word “rights.” It’s throwing sand in the face of an attacker to turn the tables and sow confusion. The essential point is that all rights are fabrications of the (collective) human mind, and thus open to debate. Granted, many of them have stabilizing societal effects and I’m not trying to argue that all fabrications are garbage. It’s just that proclaiming “rights” is a long tradition of asserting something that isn’t fundamentally real or universally agreed upon. Meanwhile most political battles boil down to a disagreement over which rights people really have. The secret: none, from a biophysical (real-world) perspective. Do we have a right to life? A fast lump of matter (bullet; falling rock) can revoke the right in an instant. Even a single naturally-sourced gamma ray can cause the right to life to expire. What rights does an alligator have? Anyone could make an argument that the alligator has more rights than a human, given their comparative marginalization on this planet and their being here first. But since they can’t articulate the “I have rights, you know” zinger, sorry: they lose. By not mastering the rules to our artificial game, alligators will lose every time. I will refrain from saying “that’s not fair.”