Last year, I was driven to draw comparisons to degrowth in Elf, a modern cinematic take on Christmas and capitalism. Watching James Caan embody an aspiring American capitalist, then climactically reject it in order to spend quality time with his family and freshly unorphaned Will Ferrell — it warms even the coldest of hearts. I was fortunate enough to watch the movie on Thanksgiving — the second film of the annual American holiday trilogy — and therefore able to put some words down that resilience.org was gracious enough to publish. This year I am a little behind, but nonetheless ready to flip down the degrowth filter on yet another legendary holiday story.

We, in modernity, cannot imagine what life looked like before the holiday existed. It remains embedded in our senso commune (common sense) as a day when families gather to give gifts that lay under the brightly lit and decorated, freshly dead pine tree. But it goes deeper than that. Christmas is the climax of the end-of-year triple-headed holiday blitz. First, we celebrate slutty demons and paganism by cosplaying, giving out future diabetes in neighborhoods where it is still considered acceptable to walk around at night in ‘Merica. Then we get together with family and strangers to celebrate colonialism and ‘big farma’ as we stuff our faces while we wait to celebrate the consumerist super bowl — capitalism’s biggest day of the year — Black Friday: this year with even fewer deaths!

[My unsolicited rebrand of the holiday formerly known as thanksgiving: center the holiday around getting together with friends, family, and random humans to celebrate how fucking cool it is when people stop working for a second and enjoy building community around a meal. Call it communesgiving or, come give, come and give thanks, give thanks and come, come on — give thanks…whatever, we’ll decide it communally. As for Black Friday, we can keep it but only if all the profits generated are given to black people.]

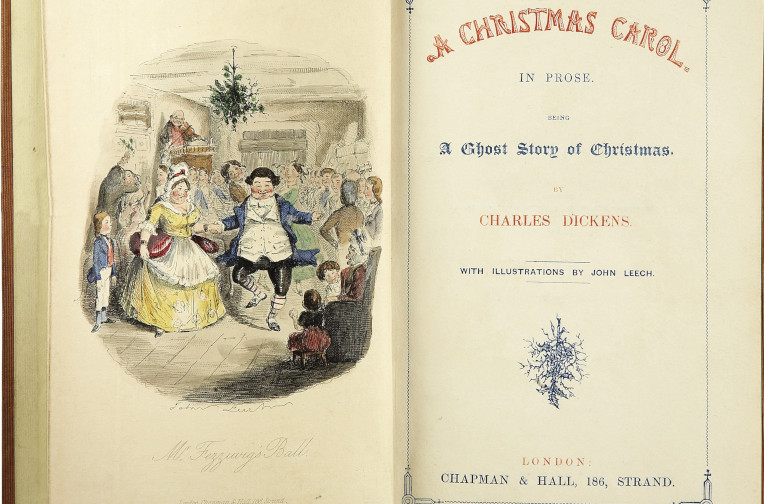

A Christmas Carol is possibly the single most important humanitarian holiday tale of the industrial era. It did not just put the merry in Merry Christmas, it universalized the greeting itself. Christmas — as we know it — would not exist without Charles Dickens’ novel novella. The story is my favorite thing about a holiday I’ve celebrated — sometimes begrudgingly — for 37 years straight. Until this year I had never heard the entire story, nor seen it acted out. I remedied it recently at a tiny community theater in Baltimore, Maryland. I could not help but be caught up in a wave of emotional epiphanies, as actor Phil Gallagher masterfully narrated and played all the characters — just as Dickens did after its original publication 180 years ago.

The story is not long, though it has been shortened and refocused in many of its replications throughout time and space. My societal reference point to the story is the Muppet’s Christmas Carol, watching it dozens of times in childhood and into adulthood. While the Muppets can do no wrong, their version lacks the lyrical beauty of Dicken’s playful prose, other than the first lines of the novella “Marley was dead to begin with.” Jacob Marley is an oft-forgotten character. He only shows up only once towards the beginning of Scrooge’s “acid trip”, yet Marley’s recounting of his miserable miser existence to Scrooge is the kernel that begins to crack Ebenezer’s ego. The dead money-lender rants on about how his love of money made him so miserable that he is suffering in the afterlife for it.

We all know the story from there. Scrooge visits his past, to a time when he lived in a country town working for Fezziwig, who despite being a debt collector/money lender, knew enough to bring his community together and get his dépense on. Ebenezer visits his present to see how everyone else in his periphery is enjoying themselves not in spite, but despite his absence. He then travels with the ghost of things yet to come to see the aftermath of his and Tiny Tim’s death. He wakes up a changed man who not only sends the Cratchits the biggest bird he can feasibly find, but lives a changed life from then on.

I have obviously no idea who Charles Dickens actually was as a person, but the impact of his art brought about societal change. In 1842, the 3 C’s (capitalism, colonialism, and Christianity) still reigned supreme. Christianity was reinventing itself in the face of liberalism, but nonetheless still the dominant western religion. Colonialism was entering its heyday, with dozens of countries now participating in the extraction and exploitation project. The new world had been conceived as the new garden of Eden — a plan commissioned by the Christian God himself. And Capitalism was about to kick into overdrive with the onset of the industrial revolution. Trains, planes, and automobiles would all be invented and subsequently capitalized upon within the next 50 or so years.

Dickens lived in London, and had been increasingly concerned by the state of the metaphorical-heartbeat of capitalism. At this point in time, Christmas was not celebrated in the cities, primarily because the weekend did not exist, nor did unions or child labor laws. This was not a time to slow down — quite the opposite in fact. The 3 C’s had succeeded in convincing men that they were separate from the world. Innovations and inventions were created with the goal of understanding the world around us, but also to manipulate and profit from. Prosperity was our gospel, production was our king, growth was our god.

The cities in Europe, such as London, were completely overrun in abject poverty. People flocked to the city, not because they sought better lives, but because they had no other way of living. The persistent privatization of the commons prevented many from living simply off the land, as they had for generations past. Dickens, aware of the deplorable working conditions for factories and mills employing children, determined to use his writing abilities to affect change, wrote the carol in a few short weeks. He supposably drew inspiration from his father’s duplicitous demeanor in creating the character of Ebenezer Scrooge.

The playful polemic was universally heralded by masses, selling out its first edition in less than a week. Within two months it had eight stage adaptations. It became so popular that it was illegally reprinted, which Dickens in his hubris nearly went broke pursuing legal action. The themes of charitable giving, forgiving debts and grievances, slowing down, and sharing a meal had near immediate impacts in society. People were literally nicer to each other. In 1867, after witnessing a performance, a factory owner proceeded to shut down his factory on Christmas — sending everyone home with a turkey. Cities got a little bit cheerier and a tad quieter around the 25th of December. Maybe some contemplated the teachings of Jesus, its condemnation of wealth, and how that might apply to them. Some interpret Scrooge’s transformational journey as a Christian allegory for redemption. However it is regaled, the story, reinterpreted for subsequent generations, has taken on an interminable legacy.

A Christmas Carol is so embedded in our cultural fabric, scrooge is in the dictionary and therefore playable in Words with Friends. At the onset of the neoliberal era, the animated Uncle Scrooge brought to the character a capitalist makeover, waltzing around with a gold-tipped cane and swimming in his silo of money. In 2017, The Man Who Invented Christmas was filmed to dramatize Dickens’s quest to make the world a better place. Whether we acknowledge it or not, he did. Did he end the hegemony of the 3 C’s? Clearly not, but let it be a lesson to all the would-be world-changers out there — the power of art should never be underestimated. The morality evoked from one short, fanciful story is still alive nearly two centuries later.