Earlier this year I worked with the UK Agri-foods for Net Zero Network (AFN for short) to help them develop a set of scenarios about the future of food production and consumption. The group includes academics, practitioners, and policy-makers. The purpose of the scenarios was to stretch their thinking around the types of research that could help to accelerate the transition of the sector to Net Zero.

The project report has been launched, and so I am able to share the scenarios and some of the methodology here.

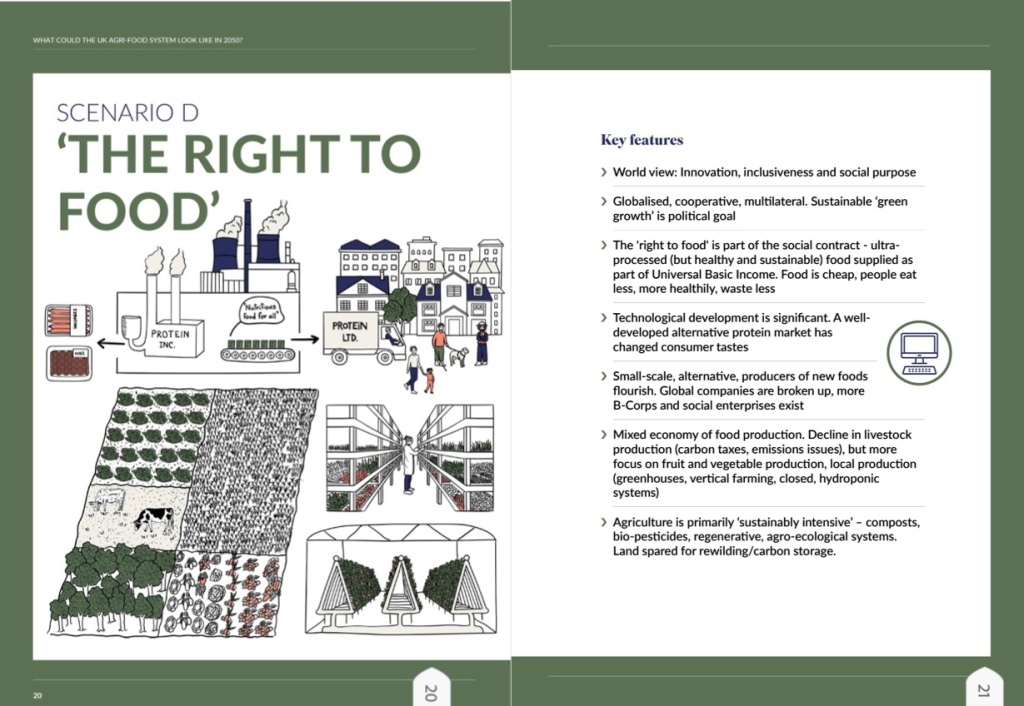

The scenarios first, though: four emerged from the process, which is their final iteration are called ‘Build Back Fast Again’; ‘Circular Worlds’; ‘Self-Sufficiency for Security’; and ‘The Right to Food’.

(Source: Benton et al, ‘What could the UK agri-food system look like in 2050?’ AFN.)

The pdf has a little infographic that summarises them.

(Source: Benton et al, ‘What could the UK agri-food system look like in 2050?’ AFN.)

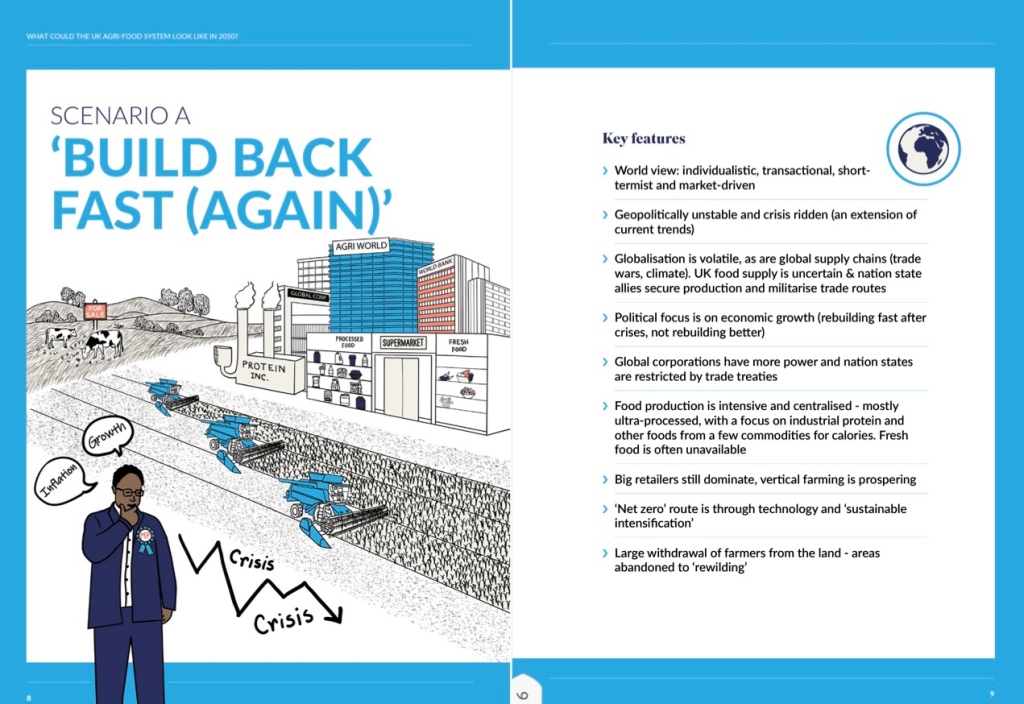

The first of these is, generally, a ‘business as usual’ scenario, with large global agricultural corporations running the show, and governments relying on world markets to feed themselves. It is in there, as with so many BAU scenarios, to test whether this is a sustainable future. In short: it is not. And since there is a good visual summary of each of the scenarios in the report, I’m just going to paste in the spreads as I go, rather than describe each scenario at length.

(Source: Benton et al, ‘What could the UK agri-food system look like in 2050?’ AFN.)

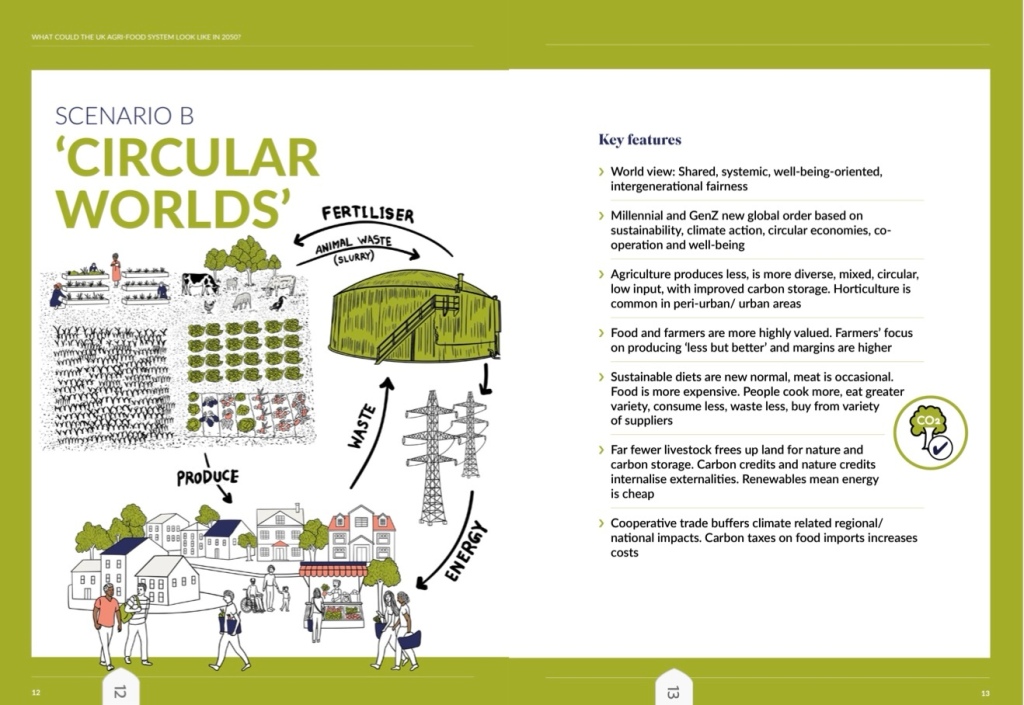

Agro-ecology

The second, ‘Circular Worlds’, draws on ideas about agro-ecology. All of these workshops took place under a version of the Chatham House Rule, and so I shouldn’t say who spoke to this scenario as it was being developed, but the report notes that Bob Costanza is one of the group’s Network+ champions, so you can probably draw your own conclusions.

I’m not sure that we quite bottomed out the productive capacity of this scenario—that may become one of the research questions—although this topic is the subject of a live and acrimonious debate at the moment between Chris Smaje (who thinks yes) and George Monbiot (who disagrees). Neither of them were involved in the process, by the way.

(Source: Benton et al, ‘What could the UK agri-food system look like in 2050?’ AFN.)

The third scenario is driven by food security, in a world where food imports are erratic and governments know that hungry citizens lose patience with them. (Perhaps the moving spirit behind this scenario is Andrew Simms’ notion that we are ‘nine meals away from anarchy’). FN Andrew Simms wasn’t involved in the process either.

(Source: Benton et al, ‘What could the UK agri-food system look like in 2050?’ AFN.)

Values-driven

I was involved in stewarding the fourth scenario (it’s unattributable, but I think I am allowed to out myself), and it was striking how hard it was to get this to a position where it was stable and didn’t keep converging with Scenario A, the big business ‘Build Back Fast Again’.

The reason for this is that it requires businesses that are values-driven, and those participating in the workshops found it hard to imagine this world. (When you watch the actual behaviour of the large food sector businesses, as most of them lobby hard against the lightest public health-driven regulatory intervention, it is possible to understand why this might be.)

Although I am not in general a fan of the conventional wisdom that says scenarios need to have both a future story and a coherent path that gets you from here to there [1], in the end it was necessary here. The path involved a combination of tough national anti-trust/ anti-monopoly legislation, and a shift in values in which the idea of purposeful business became much more central. (Because values change over time, and Gen Zs and Millennials will be running these businesses long before 2050).

Here’s this scenario:

(Source: Benton et al, ‘What could the UK agri-food system look like in 2050?’ AFN.)

The big uncertainties

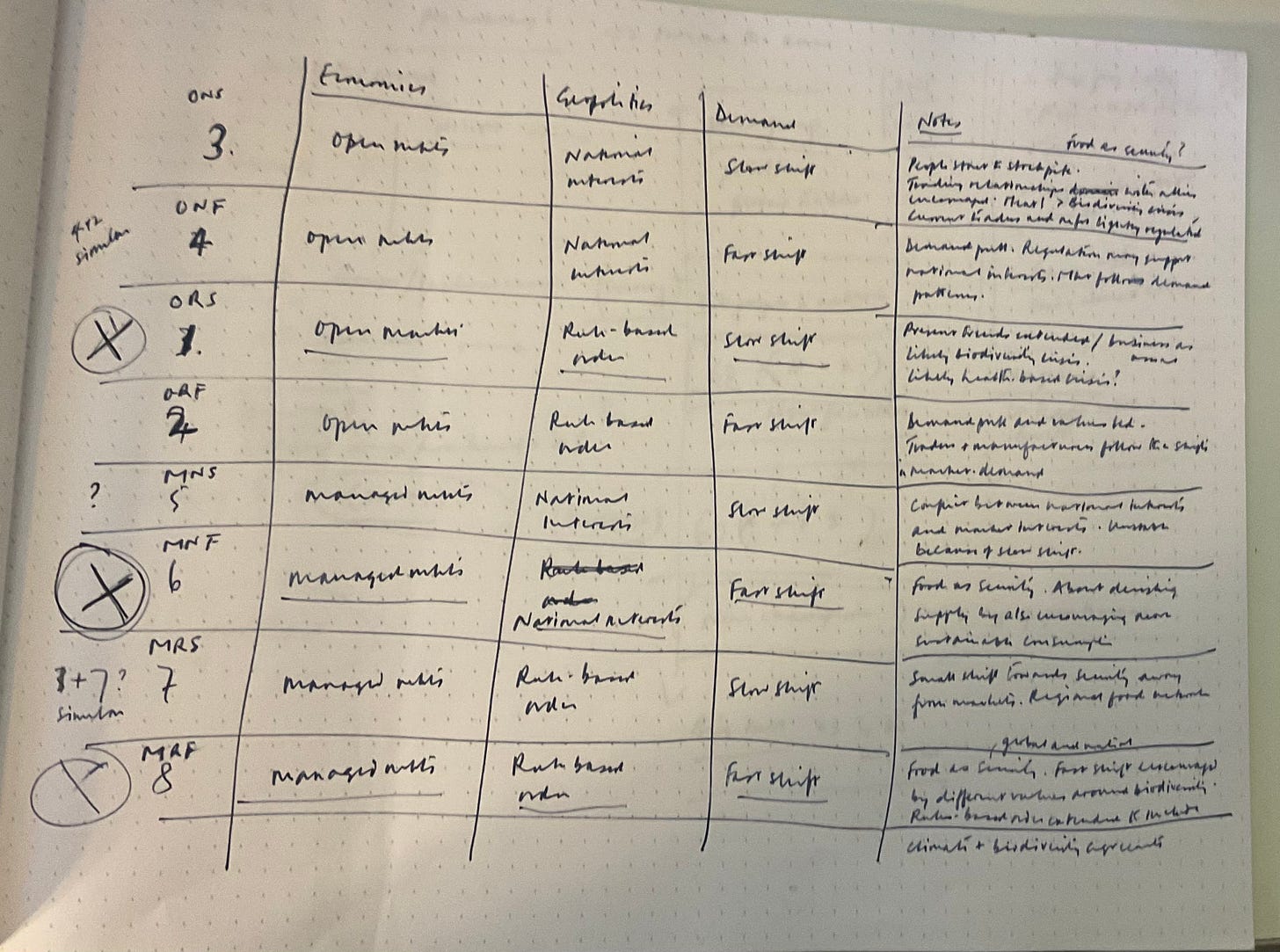

It’s worth going back briefly to discuss the process. We started with a 2 x 2 x 2 matrix that created eight possible scenarios, based on existing research that suggests that there are three big uncertainties:

Geopolitics and stability: Will the world be more volatile, conflicted and contested or return to cooperative, rules-based and calmer?

Economics: Will we rediscover open, global markets and drive back towards globalisation, or move towards more regionalised, regulated and securitized markets?

Demand: consumption-based growth or more sustainability: How will demand for the goods from land evolve? Will it grow unfettered, or will it decouple from resource demand, through price signals and sector or system innovation?

Obviously eight scenarios is too many to work with, so we removed scenarios that seemed incoherent or looked similar and less interesting than another one. (FN The formal set of criteria is described in an Annex to the report.) As it happens, I found my worksheet for this last week.

(Source: Andrew Curry. CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

The first in-person/hybrid workshop built out a set of scenarios from a set of sketches by looking at food through an international and geo-political lens. The second—shorter and online—use Verge to bring the scenarios to life in a UK context, and the third, also online, used Three Horizons to explore emerging questions in the H2 space.

Validation exercise

It’s not included in the report for space reasons, but I also did a validation exercise to ensure the diversity of the final scenarios set. They map well onto James Dator’s four emerging futures (Growth, Transformation, Collapse, Discipline, respectively). I also used Sagiv’s cultural and social values pairs (see page 9) as a second test: again, each scenario corresponds to a different one of the four combinations.

In terms of the project outcomes, it was about assessing future research needs. The report observes that these are quite different from current perspectives as soon as you move away from the ‘Business as Usual’ scenario:

It is agro-ecologically intensive in Scenario D (‘The right to food’) and features smaller, more diverse, mixed, low-synthetic-input systems in Scenarios B (‘Circular worlds’) and C (‘Self-sufficiency for security’). All also have increased circularity. Should we be preparing, through funding our R&D and innovation ecosystems, for different forms of agriculture (different crops, grown in different ways, within different farming systems, in different amounts) to ensure we are ‘future-ready’, whatever the future holds?

Normatively better

The second observation is that—contrary to pessimistic views of the future—some of these scenarios are normatively better social futures:

Are we investing enough in understanding and unlocking system transformation from the more dysfunctional futures (Scenarios A, C) to the more equitable ones (B and D). In the midst of this, how can we prioritise pathways that maximise co-benefits for human health and biodiversity?

As the report concludes: it would be good to get to Net Zero. And it would be better to get there “in a more socially just world.”

[1] Long story short: there’s research that suggests that this narrows our cognitive ability to imagine a broader range of possible futures.

——

A version of this article is also published on my Just Two Things Newsletter.