[ Part 1 of Visit to a future sustainable neighborhood ]

While visiting the future sustainable neighborhood, I came across a small group of people filling in potholes in the road, one person from the town public works department, with a few neighborhood volunteers.

During their tea break, I congratulated them on their sustainable neighborhood, asking them how it came about. They told me that in their past, supply chain disruptions started to occur more frequently, especially for food, made worse by resource depletion, reducing the amount of ‘stuff’ available. At first, political parties blamed each other for what was happening, but it became apparent to the general public that this was bigger than that. This was the new normal. People woke up to the change that was needed to create a sustainable society. Along with these disruptions and others – the increased use of robots and the AI revolution – many job opportunities evaporated.

Pretty soon, the time was right to introduce UBI (Universal Basic Income) for everyone over 18, in the minority industrialized nations: a monthly check to help take care of basic necessities. It was quite a struggle as the tax code had to be changed to get the wealthy and the corporations to pay more of their share to the common treasury.

Next, people realized that if they got free from the mesmerism of consumerism, their lives would be more manageable. That led to what they now call, The Basic Needs Economy, which included: nutritious food and water, adequate shelter in all seasons, adequate clothing for modesty and protection, adequate healthcare from the healthcare industry and lifestyle responsibility from the people (not currently the case in my society), sufficient income for their needs (not wants), safe neighborhoods and inclusion within a community or communities.

Along with this new initiative mass production was reduced, leading to even less work. Planned obsolescence in consumer goods was made illegal and the right to repair was made mandatory. As some work opportunities disappeared, others opened up.

For instance, with the new mentality evolving almost daily, re-use, reduce, recycle, upcycle, and clean-up became one of the new frameworks that people embraced. The concept of fashion, in all products, from clothes to cars, went against this increasing awareness. The slavery to brand names and the pushers of fast fashion were now seen as anti-social. Public pressure mounted to curtail advertising, especially in public spaces. A de-witched state of mind was taking hold, they told me, as opposed to a be-witched state of mind. Realizing that advertising was constantly bombarding them with messages of dissatisfaction and discontent, people rebelled saying, “no, stop the con, we choose contentment.”

They told me the financial system went on a roller-coaster ride. The big players, the wealthy and the corporate interests continually trying to prevent the new world from being born, warned that the new consciousness would bring the world to an end (as they had been in less obvious ways for decades). Growth, although essential for capitalism, was seen as fatal for the planet. And so some experts developed alternative economic strategies that respected planetary boundaries, like Doughnut Economics, which stated that the economy should be designed for us to thrive, not grow. It was time for the economy to serve the people, not the people to serve the economy.

During the plague (pandemic) of the early 2020s, changes suddenly occurred overnight that were deemed impossible months earlier. Back then, people discovered how essential certain workers were and so income for farm workers (farmers), school teachers, police, healthcare and social workers became subsidized on top of UBI. More equity in wage structures were implemented, realizing influential people had their thumbs on the scale for way too long.

Once this sustainability revolution started to take hold, the ‘great sorting’ of deciding what was essential and what was simply voracious desire, reshaped many areas of society. And so it was decided to de-commodify food, education and healthcare, in line with a more ecological form of economics, where Nature has a seat at the boardroom table.

Since the first pandemic times, citizens continued an exponential interest in organic, home edible gardening. This increased the awareness around food security, leading to a re-localizing of food systems worldwide, that was still ongoing. Running parallel with this was the natural step to build locally-sourced lifestyles.

All this meant that the Agricide form of agriculture, once one of the biggest polluters in the world, using excessive chemical inputs from fossil fuel sources, was much reduced, leading to regenerative agricultural practices, and small localized farms established everywhere. Plant based eating had increased, alleviating the destruction of rainforests for pasture and animal feed production, which led to people re-skilling for home cooking again, reducing their dependance on ultra-processed food intake, shown to be one of the largest contributors to ill health.

Fossil fuels, they told me, weren’t completely out of the picture, but much reduced through smart design – like nationwide, subsidized insulation of the built environment, etc., and renewable energy sources tipping the balance – that they were no longer considered the big problem. In fact, through the new initiatives their availability was able to be extended for a long time into the future, to assist with projects like taking care of all the obsolete atomic power infrastructure around the world that would need babysitting for thousands of years to prevent it from destroying Nature itself, through radiation leaks.

Apparently, the education system teetered on the edge for a long time before it collapsed, for many reasons, and had to be re-imagined. Eventually, a self-reliant, systems-thinking education model developed for the 5 thru 12-year-old curriculum. This included mandatory outdoor education, with school properties re-designed to accommodate sufficient naturally dense landscapes to aid learning. When I asked what the systems-thinking component meant, they said in unison, like it had become a new mantra, “System: A set of elements or parts that is coherently organized and interconnected in a pattern or structure that produces a characteristic set of behaviors, often classified as its ‘function’ or ‘purpose’.” Evidently it had been codified by Donella Meadows at the beginning of the 21st century. “Ah, you mean a kind of holistic approach?” They all nodded in unison.

What they called ‘corporate education’ continued after that – what I might be familiar with – the track to university, the trades or other work. I surmised that this led to some really well-rounded kids. “With an enthusiasm for learning that didn’t exist before,” they assured me. They said that when they first entered this new age, their education and skill sets left many adults completely unprepared to deal with the present reality, and that they were still in the process of re-skilling. Hence, they said, the new Hentrepreneur center.

One young woman, volunteering on the road crew, told me, “As the unsustainable crises deepened, the faith communities had to reevaluate their relationship to nature and their place in the general community, realizing we all needed each other, being in this together.”

“A kind of humility?” I suggested.

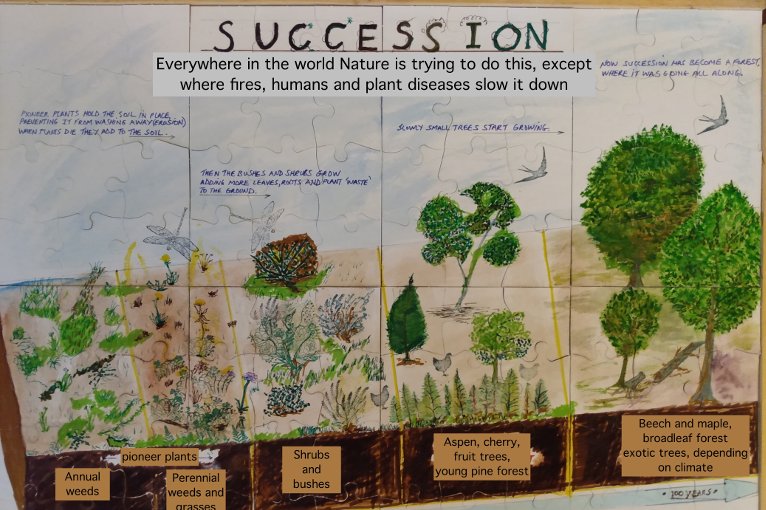

“I wouldn’t go that far, but certainly there was a lot of soul searching, shall we say. In my congregation, we invited ecologists to educate us about Nature,” she went on. “We learnt things like ‘Succession,’ where every piece of soil, left undisturbed by human activity, progresses from weeds to rain forest, with enough time. They asked us to drop the ‘thou shalt have dominion over the Earth’ rhetoric, and consider, ‘Thy will be done,’ and that Nature may display some of that will. People’s fear of slipping into Nature worship gave way to the awe of Nature, as God’s will. And as we delved deeper into Nature, we realized, despite our modern education, how little we knew about the world around us!”

As I returned to my present, savoring the conviviality of the road-crew and that neighborhood, I thought, that’s a place I’d like my grandchildren to live.

© Tony Buck (posted on Resilience by permission)