The global energy crisis, driven by surging gas prices, has decisively dented the prospects for the fuel’s future growth.

As a result, the “golden age of gas” predicted by the International Energy Agency (IEA) in 2011 is “nearing an end”, says the agency’s chief Dr Fatih Birol, with gas now set to peak by 2030.

Countries around the world are turning away from gas as high and volatile prices make the fossil fuel less economical, while the costs of alternatives decline.

Yet plans for new oil- and gas-fired power plants actually grew by 13% last year, especially in China and Southeast Asia, according to our new report at Global Energy Monitor (GEM).

Our tracking shows there is now 783 gigawatts (GW) of oil- and gas-power capacity under development – projects that are either announced or in the pre-construction and construction phases. These represent a stranded asset risk of hundreds of billions of dollars and potentially locking in tens of billions of tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions.

The overwhelming majority of this capacity is gas-fired plants, with only 7.5GW of exclusively oil-fired power plants in development.

If these new fossil-fueled power stations are completed and become operational, they could divert resources from more cost-effective and lower-carbon alternatives.

Globally widespread development

In the year to July 2023, the capacity of oil- and gas-fired power stations under development around the world grew by 90GW (13%), reaching a total of 783GW, according to the latest figures from GEM’s Global Oil and Gas Plant Tracker (GOGPT).

(Projects “under development” are those that have been announced or are in the pre-construction and construction phases, but are not yet operating.)

If they are all built, these projects would grow the capacity of the global oil and gas power fleet by a third, at an estimated cost of $611bn in capital expenditure, our analysis shows.

We also found that these plants would emit more carbon dioxide (CO2) in their lifetimes than the US generates in six-and-a-half years – some 41bn tonnes of CO2 equivalent – if they were operated in line with historical averages.

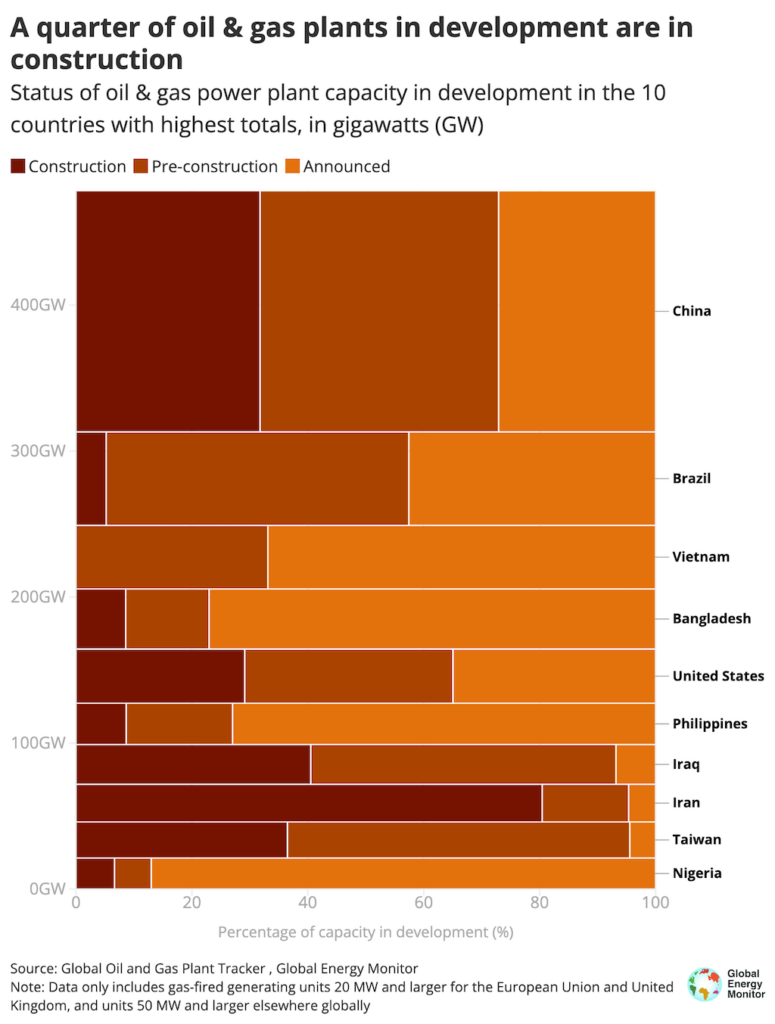

To date, only a quarter of the 783GW of capacity under development is already being built, shaded dark brown in the figure below, with the remainder being in the pre-construction (mid-brown) or early phase of development (“announced”, orange).

As the chart shows, the top 10 countries for planned new gas- and oil-fired capacity are spread across four different continents: Asia, North America, South America and Africa.

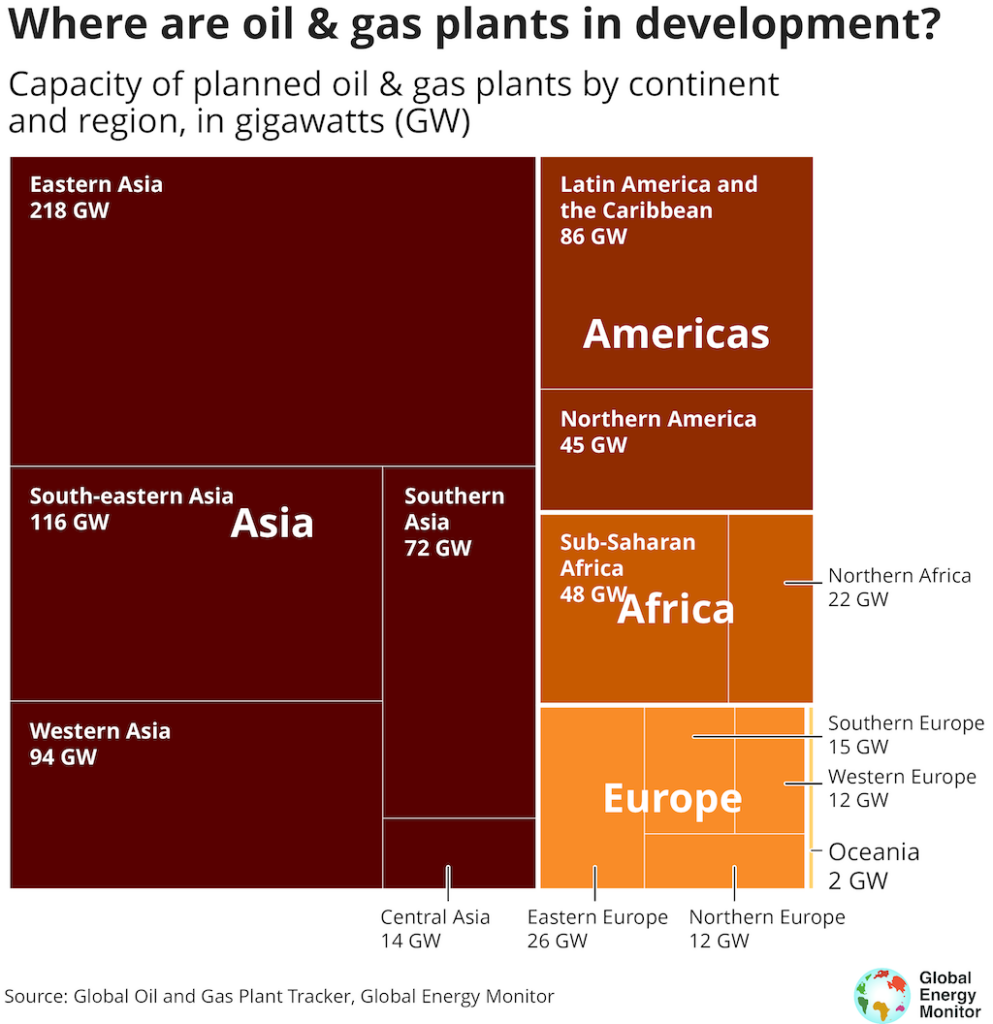

Every region of the world has significant quantities of new oil and gas-fired power in development, as shown in the chart below. However, the largest concentration is in Asia, which is home to 514GW – some two-thirds of the global total.

Asia leads gas expansion

About two-thirds of global gas- and oil-fired electricity generating capacity in development is located in Asia, according to our analysis.

Countries in east and south-east Asia are pursuing plans to either begin importing liquified natural gas (LNG) or expand domestic production, while western Asia (which includes many Middle Eastern nations) continues its long-standing reliance on gas-fired power generation to meet its energy needs.

(GEM refers to the United Nations’ geoscheme for western Asia, which includes: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Cyprus, Georgia, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Türkiye, United Arab Emirates and Yemen.)

Globally, China leads the development of new gas power capacity, with 21% of the world’s total under development and the largest increase compared to last year, we found.

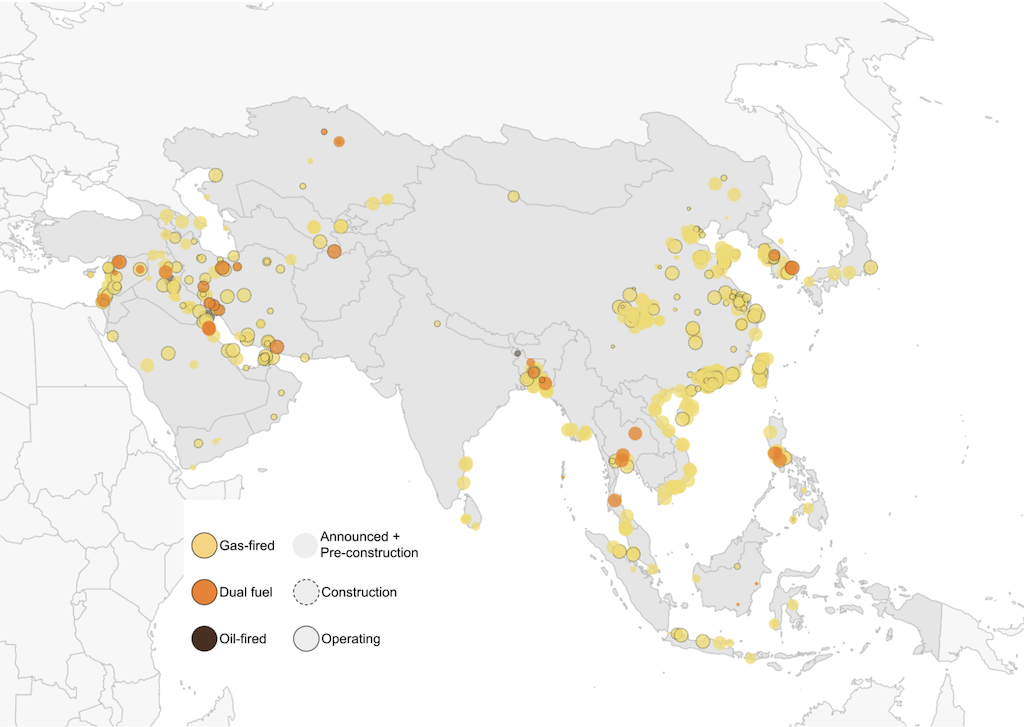

The distribution of oil- (black), dual-fuel (orange) and gas-fired power plants (yellow) across Asia is shown in the map below. Operating sites are shown with a closed circle while those under construction are dashed and those in earlier stages of development open.

Locations of oil- (black), dual-fuel (orange) and gas-fired (yellow) power developments in the Middle East and Asia. The size of each circle is proportional to the project capacity. Each location’s outline indicates its current status as already operating (solid line), under construction (dashed) or in earlier stages of development (open). Source: GEM.

Transition risks

The key drivers of the push to increase gas power capacity include energy security, rising energy demand and the increasingly questioned idea of gas as a “transition” fuel, our analysis shows, while arguments around the stability of electricity grids appear to have receded.

Nevertheless, the volatility in gas prices has pushed countries such as Pakistan and Bangladesh away from reliance on imported LNG, with supplies of the fuel likely to remain tight for several more years, according to the IEA.

At the same time, the fragility of the fossil-fuel system in the face of extreme weather events has been on display this year.

In the Middle East, for example, gas turbines buckled under rising temperatures, while arctic blasts in parts of the US caused power outages as coal and gas plants broke down.

Within our totals there are nearly 98GW of coal-to-gas conversions or replacements under development globally, more than 60% of which is in Asia, our latest figures show.

This is despite the fact that shifting directly from coal to low-carbon electricity would, in many cases, be cheaper than shifting to gas. The TransitionZero “coal-to-clean price index” shows that solar or wind with storage is cheaper than gas power in China, for example.

In general, expanding oil- and gas-fired electricity generating capacity creates a potentially costly stranded asset risk, as new infrastructure may end up as a liability before the end of its anticipated economic lifetime, GEM’s analysis suggests.

This is because many gas and oil plants would need to operate limited hours or retire before they complete their full life span, if global climate targets are to be met.

Furthermore, oil and gas power expansion could divert resources away from the transition to low-carbon energy supplies. According to the IEA, global renewable energy needs to triple by 2030 to keep the world on track for 1.5C of warming by 2030.

Over the past year, renewables became even more cost-competitive, despite inflationary pressures, because gas costs rose even faster.