A while back I wrote a post pointing out a way to see that animals are worth more than their weight in gold. The concept was cute, but not fully defensible in detail. Yet, the many orders-of-magnitude difference in market value of animals vs. their gold-equivalent value at least indicated that we might have something wrong, on the basis that we can’t live without the animals, but could live without gold.

In this post, I will follow a similar path to arrive at what I think is even a more stark result: that the economic value of arthropods (e.g., insects) is something like $10,000 per kilogram. To get here, we need to first preview the numbers.

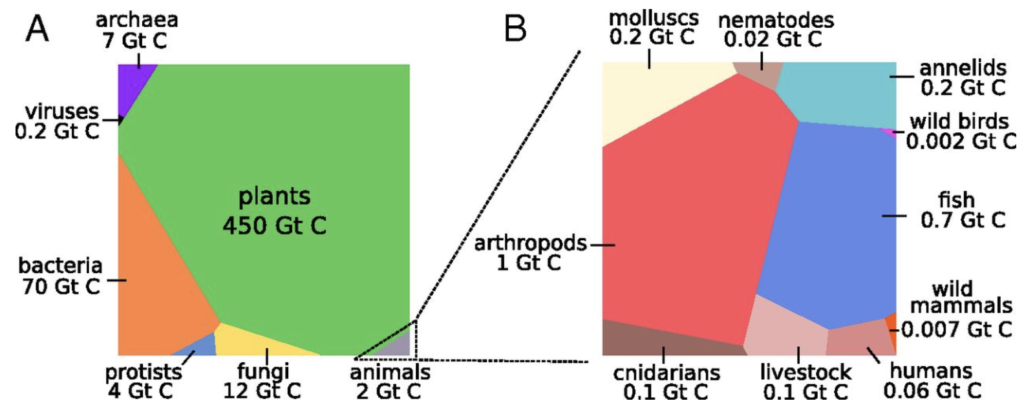

Dry carbon biomass on Earth, from Bar-On, Phillips, and Milo; PNAS 115, 6506, 2018.

A look at Figure 1 in a 2018 paper by Bar-On at al. (reproduced above) shows that Planet Earth hosts 2.4 Gt (giga-tons) of animals, in terms of dry carbon mass. The largest block within the animal kingdom is arthropods (includes insects, spiders, centipedes, and crustaceans), at 1 Gt. Fish are nearly as big, at 0.7 Gt. By contrast, wild mammals are only 0.007 Gt, and wild birds are a comparatively tiny 0.002 Gt.

I have pointed out before that humans now vastly outweigh wild mammals, to the point that we only have 2.5 kg of wild land mammal mass left per human on the planet (presently plummeting). Note that this is a “wet” mass figure, whereas the numbers above are dry carbon mass (about 15% of wet mass).

The trends are falling fast: insect, bird, mammal, amphibian, and fish populations are losing ground to the tune of 1–2% per year, amounting to halving populations over a handful of decades. Inevitably, then, extinctions are up a thousand-fold, and increasing. This is decidedly not good, and perhaps the most glaring sign that modernity is a literal dead-end path.

The approach here is to assume that Earth’s ecology would crash without any arthropods. The same might be said for fish, or birds, or any major group. Bugs (an informal catch-all substitute for arthropods here) are particularly attractive to me for this exercise because they are so crucial in terms of food for others, soil conditioning, pollination—and other services—that it is hard to believe other phyla could carry on without them. Evolution produces a complex interconnected web that cannot be expected to maintain its overall integrity if surgically plucked apart in this way—much as an organism cannot be expected to survive if completely removing any one of many key organs.

Therefore, no bugs, no humans. No them, no us. The same argument could probably be made for other phyla, producing slightly different quantitative results than what follows, but the same in spirit.

The Value of Bugs

Okay, so I will assume agreement that we need the arthropods, as part of Earth’s biological context and as prerequisite participants in our own dance (but see other games below if still not buying it). Let’s now try another association: no bugs, no humans, no economy. Our modern market economy is not some abstraction that exists beyond the context of humans, or independent of the ecological foundation in which we are embedded. Our entire economy therefore owes its very existence to bugs.

Before assigning monetary values, I will pause to say that I only do so because our culture has been conditioned to cast most things in financial terms. Well, animals are not mere “things,” having intrinsic value that supersedes the economic realm. So, this gross exercise is aimed at the monetarily-minded, who may need some convincing that biodiversity is more important than the economy.

The global economy amounts to about 80 trillion dollars per year, which I will call $1014 for order-of-magnitude convenience. How long do you expect our economy to last, and how many integrated dollars does this represent? Opinions will vary wildly, I am sure. Likely answers would range from decades to millennia (or longer?). I’ll use one century as a benchmark. After all, IPCC reports imply that nothing happens beyond the year 2100, right? One century at $1014 per year is $1016. That’s assuming no growth. If you want growth, or a longer run, just make the number bigger. I won’t restrict your ambitions, here. Go big if it suits you.

We’re talking about a total arthropod mass of 1 Gt, or 1012 kg. If we wipe them out, the economy is caput, and we forgo something like $1016 of total economic activity (or whatever your number was). Doing the math, I get $10,000 per kilogram of arthropod mass. That’s expensive! I’ll note that this is not terribly far from the “gold standard” I derived of $60,000 per kilogram of animal mass.

A single bee has a wet mass a little over 0.1 g, which would be $1 if not correcting for the dry-carbon to wet-mass ratio, so you’d actually get about 6 bees to the dollar.

Not Literally

Obviously, our economic system is not explicitly tied to bug mass—and that’s part of our problem, I would say. So an annual loss of 1% of bugs does not translate into a 1% loss in GDP, or even more starkly 1% of the $1016 total value that’s on the line. Were that to be true, our annual GDP would be wholly swallowed by bug/insect decline, which perhaps is another way of saying that we’ve exceeded planetary limits, and are not paying for our destruction.

We also don’t pay $0.15 per bee on the planet. This is not a pedantic proposition for properly pricing insects, but is intended to point out the flaws in our overall economic valuation schemes.

We might say that bugs are economically extremely elastic and non-linear: almost zero value until they are more valuable than anything else (when on the brink of extinction). As far as the idiotic market is concerned, we now have a glut of bugs, squashing their value. In fact, we pay good money to exterminate them dead, using pesticides (hint: the “cide” suffix is erudite-speak for “murder”). Cheeky buggers, thinking our food (?) belongs to anyone but Lord Man!

What, Then?

If I am not literally saying that a kilogram of arthropods has a market value of $10,000, then what am I saying?

Think about it first.

I’m saying that our economic regime is so narrowly imbecilic as to neglect the very thing that makes its own existence possible. It lacks context. By placing essentially zero (or even negative) value on the bugs, it incentivizes its own destruction. It’s the metaphor of cutting off the branch you’re standing on: marvelous efficiency, but to an ultimately disastrous end.

How could this short-sightedness happen? Because markets can generate short term gains (profits) without consideration of such elements—for centuries, even. That’s good enough for markets to function and grow to dominate life, complete with insufferable economists bossing us about how it works. But what are centuries against the 500 million years of evolution that gave the Earth its arthropod foundation—not to mention the billions of years that set the stage for even that step? Apparently, that’s worth nothing, economically?

I should also clarify that the individual bugs don’t matter as much as the overall biomass. Individuals come and go in a continual “standing wave” of genetic representation in living form, filling crucial ecological niches. What matters is the amount (mass) and diversity of the biology at any given time, and the genetic code that keeps the population in place. In this sense, if we talk of future economic value integrated over 100 or 1,000 years, we need not tally up all the individual beings who come and go over that interval. What we care about is the (more) static total biomass, which is approximately the same from one year to the next. Although, the whole problem is that it’s not static, lately.

To restate the case, then, we are not WE without all of US: without bugs, no humans, no economy. Since we can quantify the biomass of bugs, and the economy is quantified every which way, we can calculate so many dollars per kilogram of biomass. More importantly, we can confidently state that the economic metric would be zero without bugs, and therefore owes its entire value to the existence of bugs.

Other Games

I picked arthropods because they are sufficiently foundational in the web of life that I have an easier time imagining ecosystem collapse if that particular (bug) rug is pulled out from underneath the animal kingdom (some members of other kingdoms rely on bugs as well). In doing so, I cast the net rather wide, catching both butterflies and krill. I might have preferred to use insects alone—still able to make the case. But the data I used did not subdivide into insects. Had it done so, we can be sure the insect mass would be smaller than the total arthropod mass, thereby only serving to increase their calculated economic value.

Our continuance seems likely to also depend on other groups, like all fish (in turn depending on arthropods like krill). I’m not talking about direct human consumption of fish, but imagining that the entire oceanic ecosystem would crash if suddenly devoid of a principal component, and that the domino effect would impact land creatures as well. Given that fish biomass is similar to that of arthropods (0.7 vs. 1.0 Gt), the quantitative impact is essentially the same.

But what if a world without birds also cannot hold together in viable equilibrium (or at least can no longer support humans)? I don’t know enough to present a compelling case one way or another. Perhaps someone does, but I would be skeptical—especially of the counterfactual that human existence can continue without the presence of birds. I hope no one is arrogant enough to assume enough understanding to claim any such thing, against any evidence. It’s certainly not an experiment I would have any interest in trying!

In any case, wild bird mass being 0.002 Gt, the value of our economic machine per kilogram of biomass goes up, to $5M/kg. This makes a sparrow worth about as much as a car!

Wild mammals register 0.007 Gt, which is roughly evenly split between land and sea, though a little more on the marine side. For wild land mammals, 0.003 Gt can’t be too far off the mark, similar to wild bird mass. We get about $3M/kg (dry), making for a $3,000,000 raccoon. Could humans survive without any wild mammal biomass on the planet? More to the point of this post, would the economy survive? Let’s please not try!

On the other extreme, we could throw our net wider and count the entire 2.4 Gt of animal biomass and be even more confident that we would not survive without any animals except humans on the planet. As this is only 2.4× the arthropod mass, the basic math is hardly changed: same order-of-magnitude as the case for bugs alone ($4,000 per kilogram).

A Techno-Optimist Trap

One thing I like about this exercise is that the more enamored one is of our economy, our technology, and our prospects, the more valuable animals become! The unflinching optimist will assume we can go longer and grow more, thus only increasing the total accumulated economic value of the enterprise and putting more at stake. In some sense, the less biophysically-aware a person is—placing premium value on our artificial creations—the more valuable the natural world actually becomes. Maybe that paradox will trouble the techno-love-blind mind. But no one likes a trap, so the more likely reaction is rejection of the premise, out of hand.

Wake the Fup!

This is really simple and obvious. What we might call modernity, civilization, or the “world made by humans” is a layer built on top of fundamental prerequisites like air, water, materials, and life. Humans cannot exist in ecological isolation. Our context is unfathomably deep in time and in biodiversity. The hierarchy is crystal clear: humans require ecological health rather than the reverse. This means all our constructs, which do not exist without us, cannot exist without a functioning ecology. We might be forgiven for taking a prerequisite for granted—like oxygen in the atmosphere—except when we are actively destroying the prerequisite with marvelous efficiency.

The globally-dominant culture preaches the opposite hierarchy, either out of ignorance or arrogance: that humans and our constructs are of primary concern—the rest being incidental background noise. For the human supremacist (most people in our culture, unknowingly), biophysical considerations only enter in the context of energy, materials, extraction, exploitation, and in short, market value.

Let’s be clear: the culture has it terribly wrong. Such an attitude can appear to work for a time, but the accompanying fate of the biophysical world is steady decline as one commodity after another is monetized, displacing the community of life and making various creatures’ existence progressively more difficult and dismal to the point of non-viability and extinction. Our culture might view this as unfortunate and unintended collateral damage, but not more correctly as an existential threat of our own making.

What I am saying is that a system powerful enough to destroy ecological health and biodiversity—which we have demonstrated in spades—cannot survive unless it deliberately refrains from using this power. It must invert the cultural hierarchy and place ecosystem health—the vitality of the biodiverse planet—above all other considerations…ABOVE ALL OTHER CONSIDERATIONS, to hammer the point.

We have abundant evidence that we can destroy life, at large scale, up to and including a ballooning number of permanent extinctions. It is far beyond our power to create biodiversity and life—especially pre-tuned to play a viable ecological role in the context of all other life. Only life can create itself, and only long exposure to the full world-as-it-is can shape life to work in the long term, via multi-level selection processes. While we can’t create and shape life to our whims, what we can do is get out of its way: let life do what it does best. Give it room. Make it a priority. Respect it. Live in awe of it. See it as the only thing that allows us to be who we are. Without it, we are nothing. If a person is naïve enough to think that we can engineer what we need as a replacement, then at least we can hope they have the decency to keep quiet, lest they unwittingly advocate the demise of everything they themselves hold dear. Sir: please take your hand off the saw, and carefully step back to safety, for the good of us all.