How does it feel, how does it feel?

To be on your own, with no direction home

A complete unknown, like a rolling stone

— Bob Dylan, Like a Rolling Stone

Curiously enough, the word ‘disabstraction’ barely even exists at all, insofar as dictionaries are concerned. So those among you, if you are young, may one day tell your twenty-something sons or daughters of the day you first stumbled upon the inchoate word before it began appearing in dictionaries. You can trace the word to these “notes,” for this will not be any less inchoate than notes, today. And you can say that the coiner of this word, as it applies to history and philosophy taken together, spoke of himself as a sort of truffle hunter, whether sometimes the dog herself, head down, sniffing for truffles, darting hither and thither, or the man (or woman) following the dog around.

And what are these truffles? They are a metaphor of sorts for what I’m following—a scent trail. Sometimes a scent strong enough for me, your human companion, and sometimes for a scent far too delicate and small for my near olfactory blindness as a mere human. Sometimes I must rely on the sensitive nose of a dog. And so it is with truffle hunting.

Tell your young daughter that the coiner of this specialist term in philosophy of history — and history of philosophy — mentioned Jacques Derrida’s deconstruction in passing, and that the coiner of disabstraction took note of the scent found around this deconstruction, but kept up his search for truffles, not lingering at the scent of mice or rabbits. And be sure to mention folks like Ivan Illich and Karl Polanyi (author of The Great Transformation) as creatures who smell more like truffles than like mice or rabbits.

Be sure to mention that the coiner didn’t give a mouse’s ass about fame, fortune or reputation, but was simply hungry for truffles. And do let it be known that the coiner’s interest in truffles was in service to something self-transcending — in a sincerely humble sort of way — which was rooted in his knowledge of himself as a potential ancestor — and one with a palpable sense of reputation meaning nothing in the grave, or in ashes. Tell her that he had a sense of humor, and that he only hoped to pass on a potentially useful term and concept in service to inquiry.

Happily, the word “abstract” has eight or ten major dictionary meanings. And it is possible to blend most of these meanings into a sort of singular, but also multiplicitous “blended” sense or meaning.

The prefix “dis-” in English is often used to indicate negation, reversal, or the absence or removal of something. To “disabstract” an account, a bit of history, a narrative or story, an image, idea or concept, an academic discipline or theory…, is to re-embed it in a world of history, concrete particulars, detailed situations, context, depth, richness, complexity, specificity, detail, situatedness, place… and so much more. Such are truffles! They have a unique, discernible scent.

A Direction Home

I don’t know what it means to be free, to have liberty. I don’t know precisely what modernity is. But there is something in the rhythm and the rhyme of it which suggests that, for modern people, liberty is … To be on your own, with no direction home / A complete unknown, like a rolling stone. Modernity was (and is) a myth founded on an idea of liberty which hardly anyone can believe anymore. It was a myth of a people who pull themselves up by the their lonesome ontological and epistemic bootstraps, who buried the meaning of liberty in a set of abstractions … and forgot the story of its own mythic origins.

Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose?1

Modern liberty pretended to be about us (or we) much of the time, but it soon became about me. It was a train which left the station and soon left its tracks—, derailed. A road to nowhere.2

And so, for us, beginning to know what it means to have liberty begins by not knowing where we are going. It means beginning in a shared knowing that we neither know where we’re going any more than we know where we have been. A rupture has occurred in our collective memory — of our history.

Life on the Border

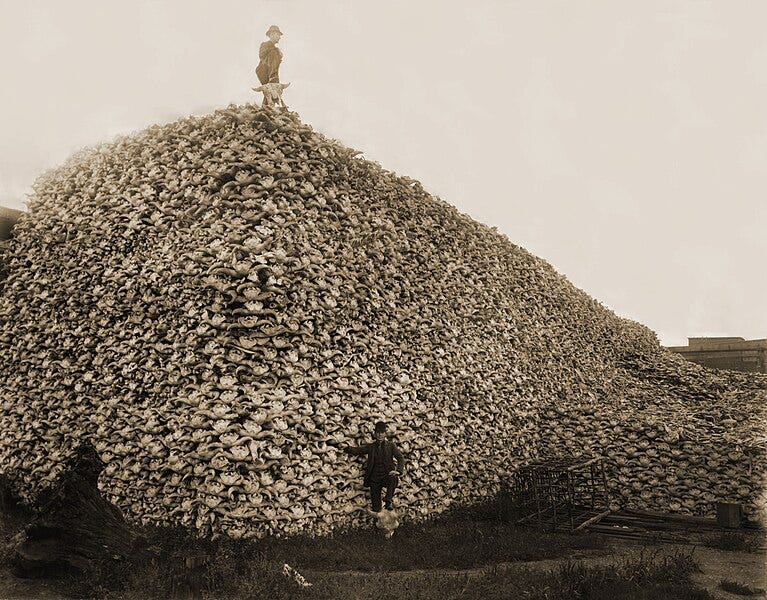

Photograph 1892 of a pile of American bison skulls waiting to be ground for fertilizer -circa 1892

Photograph 1892 of a pile of American bison skulls waiting to be ground for fertilizer -circa 1892

Flipping through television channels yesterday, I stumbled for a moment into one of the new, televised, right wing programs, in which I was being told that “The Communist Party has been assembling on the Southern border” (of the USA). WTF? The Communist Party! On the Border!

This is a new (?) kind of myth of barbarians, invasions. Sputnik! Commies. This is a step beyond the hordes from Mexico we were warned of by Trump. Now they (again) are Commies, pinkos.

Forgetting of the past becomes ignorance of the present. And anything and everything is now treated as “news”. Where are we? Are we still in the Cold War?

And this terrible news came on a day when I’d been reading, at the prompting of Chris Smaje, about one among many ways of sharing what belongs to all who were born naked here on — or, better, in Earth — : the distributists. Smaje’s essay concluded: “To that end, I’ve been discussing with an international group of colleagues the idea of a Distributist Congress – potentially as both a recurrent meeting and an ongoing political vehicle. I invite readers of The Land to contact me to express their interest, support or ideas for such a Congress, as individuals or on behalf of relevant organisations they represent.”

So I “googled” the phrase “Distributist Congress” and discovered, to no great surprise, that nothing much appears to have happened under that heading.

Freedom appears to remain a matter of not having much else to lose. (Curiously enough, I found this article from Smaje by “googling” terms which included “distributism” and “Ivan Illich”.)

And speaking of Ivan Illich, well, he was a household name in the 70’s, and today? I cannot find one of his books in any of my local bookstores, or at any of the several branches of my local public library. I ask about him, and folks look at me blankly and say, “who?”.

Noam Chomsky has said that the socialist movement, at root and at heart, wasn’t about what we now (in economistic terms) call “economic liberty”. It was mostly about having liberty enough to grow (“produce”) one’s own food (etc.) in one’s own neighborhood, to gather the necessary “products and services” (as we now call it) for livelihood right in our own neighborhood, mostly in walking distance, without permission of the “owners”. Maybe that has something to tell us about the history of “liberty”?

I don’t know. Let’s find out!?

To know is to disabstract “the economy” and “the market” — and “society” and “culture” and “civilisation”…? It’s to go searching for the present in the past, and the past in the present? Perhaps?

Maybe this has something to do with coming to our senses?

Ah, but these are — as promised — mere notes. Notes in passing. Let us see if anyone notices—, or cares.

Questions are more important and valuable than answers?

1 https://genius.com/Janis-joplin-me-and-bobby-mcgee-lyrics

2 … Well, we know where we’re goin’

But we don’t know where we’ve been

And we know what we’re knowin’

But we can’t say what we’ve seen

… And we’re not little children

And we know what we want

And the future is certain

Give us time to work it out

— Talking Heads, Road To Nowhere