This is the fifth in a series of articles addressing the global energy transition as an opportunity to reduce continuing damage and inequities and to revise the global ethic of development in favor of human and earth-centric values. (Ed. note: You can find the previous articles in the series on Resilience.org here, here, here, and here.)

Any long-natural investment, especially any resource development project requires a risk-reward analysis before launch. This has been true throughout the history of fossil-fuel development. The scale of resource extraction, the energy return on investment, the financial rewards and the presumed benefit to the whole have overridden virtually all local environmental and social concerns. The evidence is everywhere. One need only look at the Niger Delta, the rainforests of Ecuador, the Exxon-Valdez, the Deepwater Horizon disaster of 2010, the Gulf War oil spills, uncounted pipeline leaks, the Tar Sands of Alberta, mountaintop mining, ongoing water and air pollution and on and on.

As the momentum toward a net-zero world increases and as wider public awareness of the risks associated with mining rises, the industry will undergo increased scrutiny for its known risk factors, inadequate proactive policies, reporting deficiencies, and failures to remediate damages. There will be increasing pressure from civil society and governments on mining companies and lending institutions to perform responsible due diligence into critical mineral sourcing and to hold the extractive economy to increasingly stringent environmental, social and governance standards. The damage and various forms of violence already part of a well-documented history of international mining ventures, unless vigorously checked on numerous fronts, is about to explode in a proliferation of new ventures on top of the existing 35,000 existing sites globally. The most common risks include:

- Torture, cruel, inhuman, and degrading treatment

- Attacks on human rights and environmental defenders, including murder

- Forced or compulsory labor

- Violations of child labor laws

- Land appropriation

- War crimes and other violations of international law

- Crimes against humanity, genocide

- Gender or sexual violence

- Support for public or private security forces

- Support for non-state armed groups

- Financial crime, including bribery, money laundering, and tax evasion

- Work-related fatalities

- Long-term pollution of waterways

- Loss of biodiversity

- Loss of livelihoods among local communities

- Forced displacement.

- Community health effects

In the mining industry, much of the known abuse of the past has been in the precious metals sector (gold, diamonds, jade & rubies), though there has been a sharp increase in recent reporting in the critical mineral sector (cobalt, copper, nickel, zinc, lithium) as well. The accelerating search for energy-related minerals, opening new mines and scaling up production to meet demand for the clean-energy transition threatens an even greater swath of devastation across all continents as well as raising the risk levels of geopolitical conflict.

With that expansion will almost assuredly come greater corruption and human rights abuses, potentially expanding far beyond known incidents related strictly to precious metals. Mining will become, if it isn’t already, the front line where business-as-usual meets human rights and earth rights. I have already addressed water scarcity in a previous post. As demand for energy related minerals rises, the risk of sourcing metals in conflict-affected areas is also bound to rise, not to mention the risks to local ecologies.

The pressure to hold miners and governments accountable for the entire field of known risks and externalized costs will certainly encounter resistance. But it will also increase operating costs and reduce the bottom line. At some point, the ongoing destruction undermines the social license of the industry and raises the cost of financing. I believe we can expect our thirst for energy to be manipulated to permit continued ignorance of these concerns in favor of the corporate growth imperative. But at some point, as the risks become more evident, will a declining potential return on investment begin to slow new financing? Will there be a line that even Wall Street and global development banks won’t cross?

One human rights study examined nine metal ores (bauxite, copper, gold, iron, lead, manganese, nickel, silver and zinc) across approximately 3,000 sites of extraction worldwide between 2000 and 2019

….finding that 79% of global metal ore extraction in 2019 originated from five of the six most species-rich biomes, with mining volumes doubling since 2000 in tropical moist forest ecosystems. Half of global metal ore extraction took place at 20 km or less from protected territories. Further, 90% of all considered extraction sites correspond to below-average relative water availability.

Another study performed by the Responsible Mining Institute covered harmful impacts associated with 38 of the largest mining companies, accounting for 28% of global production. It is a litany of negligence and in too many cases, criminality, in excruciating detail.

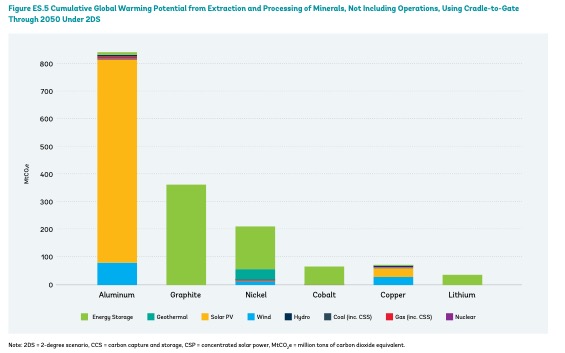

Beyond the list of risk factors above, another risk issue not fully addressed is the carbon footprint of the mining industry itself. The figures estimating emissions due to extraction, transportation and, refining are not up-to-date, but up to 11% of global energy use has been attributed to the mining industry. The World Bank estimates that integrating renewable energy into mining operations can reduce that footprint up to 40%. Given the current geographic concentration of critical mineral infrastructure and refineries devoted to rare earth and storage-related minerals, the industry footprint will come under increasing scrutiny. Not only is it of strategic importance to de-carbonize and de-centralize operations, but expanding the existing refinery network will significantly reduce the overall carbon footprint of mining operations by reducing the carbon costs of transportation alone, not to mention other possible efficiencies to be built into the system.

A surge in new mining ventures is going to overrun protected and vulnerable areas throughout the world. In the US, as stated in a previous article, the great majority of known critical reserves (68% of cobalt, 89% of copper, 79% of lithium, 97% of nickel) lie within 35 miles of native American territories. Much of the global reserves of critical minerals lie in nations high on a scale of corrupt business and government practices.

Areas important to indigenous cultures may be situated outside their reservations. The buffer zone of 35 miles was set to include the controversial Resolution and Eagle mining projects, both of which are within 35 miles of reservations. Source: MSCI ESG Research, U.S. Census Bureau’s MAF/TIGER, S&P Global Market Intelligence.

While governments may be offering incentives to expand mining, they are not providing concurrent guidance or requirements for compliance with environmental or human rights standards as aggressively as the situation demands. Indeed, any practical distinction between environmental and human rights should be discarded. If we continue to accept industry narratives or government pronouncements minimizing or representing these issues as mutually exclusive, we will continue to degrade the biological basis of life as we struggle to arrive at a fossil-free future.

The assumption that renewable energy infrastructure is going to become cheaper—by a lot—is based on shaky notions that opposition can be overcome, that energy inputs will remain plentiful and within acceptable parameters, that minerals will become more plentiful as new mines are opened, that technologies to manufacture parts will improve, chemistries will become more efficient, recycling can be scaled up and that costs per unit will be scaled down.

Against this backdrop, the close integration of a dozen (or more) mutually dependent factors such as production levels, refining capacity, human rights issues, workplace safety, geopolitical factors, environmental pollution, competition for water, declining ore grades, financial crimes, supply-chain transparency, insufficient social engagement, railroading indigenous property rights, price volatility and a declining energy return on investment present an unappealing soup of issues for the mining industry over the coming years of this decade and beyond. Not to mention that mining sites themselves will be subject to extreme climate-related events.

In addition to the studies referenced above, two widely respected NGOs, the Business and Human Rights Resource Center’s Transition Minerals Tracker, and TDI Sustainability’s Trends in Stakeholder Reporting: Mineral Supply Chains have each reported on human rights abuses involving over 500 companies in 200 jurisdictions over the past decade. The greatest number of all recorded allegations referred to a small group of companies involved in mining just six minerals: cobalt, copper, lithium, manganese, nickel, and zinc. Copper was determined to be the most dangerous metal for human rights abuses, even greater than cobalt.

Aside from production and supply chain considerations, whether the industry can raise its performance to meet a proliferation of new standards will be a challenge. The entities engaged most closely in recording abuses and developing standards are: Index for Risk Management, World Governance Index, Amnesty International, UN Committee Against Torture, Global Database on Violence Against Women, US Department of Labor, International Labor Organization, the Heidelberg Institute, the Financial Action Task Force and the Extractive Industry Transparency Initiative and Global Witness.

Whether emerging standards will ever have real teeth will depend on broad government support and the truly novel creation of sufficient enforcement mechanisms. If past is prelude, a more bloodless view would suggest that miners will extend their capacity to skirt popular, political, financial, and regulatory oversight and push their social license to within an inch of its life as long as possible, i.e., assuming financing continues to be available for new and ongoing projects.

The World Bank is one of those financing institutions. In its own report, Minerals for Climate Action, it estimates that “Three billion tons of minerals and metals will be needed to realize the Paris Agreement‘s goals of net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050” (Such a haul will create nearly 100 billion tons of mine waste). While it has advocated for developing nations to adopt strong regulatory and legal frameworks to protect the environment and communities and opposed cultural dislocation and destruction since the mid-80s, it has also allegedly violated its own policies, displacing more than a million people each in multiple countries for the sake of power, water and transportation development.

Given the past failure of private financing for World Bank projects to protect either human rights, verifiably reduce poverty or guarantee environmental protections, with virtually no enforcement and no penalties for violations, there appears to be no truly sustainable principle driving such investments other than profit. Demands for meeting investor standards for profit margins to cover risk or to make the investment ‘attractive’ are regarded as unreasonably high, virtually guaranteeing that environmental and human rights standards will continue to be diluted if not ignored or violated outright.

The International Finance Corporation (IFC), a member of the World Bank Group, responded to lawsuits this way:

In 2015, represented by the environmental law practice Earth Rights International, three communities affected by Tata Mundra sued the IFC in U.S. federal court. The IFC asserted it had “absolute immunity” from prosecution under the International Organizations Immunity Act (IOIA), arguing that losing such immunity could “produce a considerable chilling effect on IFC’s capacity and willingness to lend money in developing countries” and open “a floodgate of lawsuits by allegedly aggrieved complainants from all over the world.” In 2019, the Supreme Court denied this argument of immunity in a 7-1 decision, though lower courts stated the IFC was immune on other grounds.

The average consumer may not make a direct connection between widespread and profound environmental destruction and accessible consumer conveniences until either dramatic price increases or interruptions of supply occur. The primary interest supporting the uninterrupted expansion of mineral extraction comes from downstream industries (utility scale power supply, automakers, and consumer electronics) whose survival (and market influence) depends on increasingly desperate efforts to grow their business and retire their existing debt.

As Nate Hagens has described, the collapse of that chase is only a matter of time. This is the imperative of consumer capitalism even as it extends itself into its latter stages: sustain the myth of sustainability. The extractive economy producing cheap energy has fueled growth for the past 150 years. Permitting it to falter is not an option. But to what extremes are we willing to go to make sure it doesn’t? Is a just clean energy transition even possible or will the system collapse under its own weight before that question is answered?

Citations:

Can the World Bank’s New CEO Change Their Toxic Lending Practices?

Harmful Impacts of Mining, Responsible Mining Foundation

How the Rush for Critical Minerals Threatens Human Rights.

Mining Energy-Transition Metals: National Aims, Local Conflicts

Mining Critical to Renewable Energy Tied to Hundreds of Alleged Human Rights Abuses

Mineral Rich Developing Countries Can Drive a Net-Zero Future.

Minerals for Climate Action: The Mining Intensity of the Clean Energy Transition

Nate Hagens: The Great Simplification

Policy Approaches to Climate Change in Mineral Rich Countries

Recommendations of the Global Commission on People-Centered Clean Energy Transitions, IEA.

Redefining “Critical” Minerals Essential for a Clean Energy Future

Trends in Stakeholder Reporting: Mineral Supply Chains