What exactly is the doughnut? Think of it as an economic compass, artfully crafted to address people’s needs while also respecting the Earth’s boundaries and the vitality of our planet. This innovative concept, pioneered by Kate Raworth in her book “Doughnut Economics. Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist,” takes on the shape of, well, a doughnut! This visual metaphor aptly captures a wealth of research conducted in the field of ecological economics. Ecological economics, a multidisciplinary approach, seeks to simultaneously tackle the challenges of social sustainability and environmental well-being.

Representing planetary and human needs

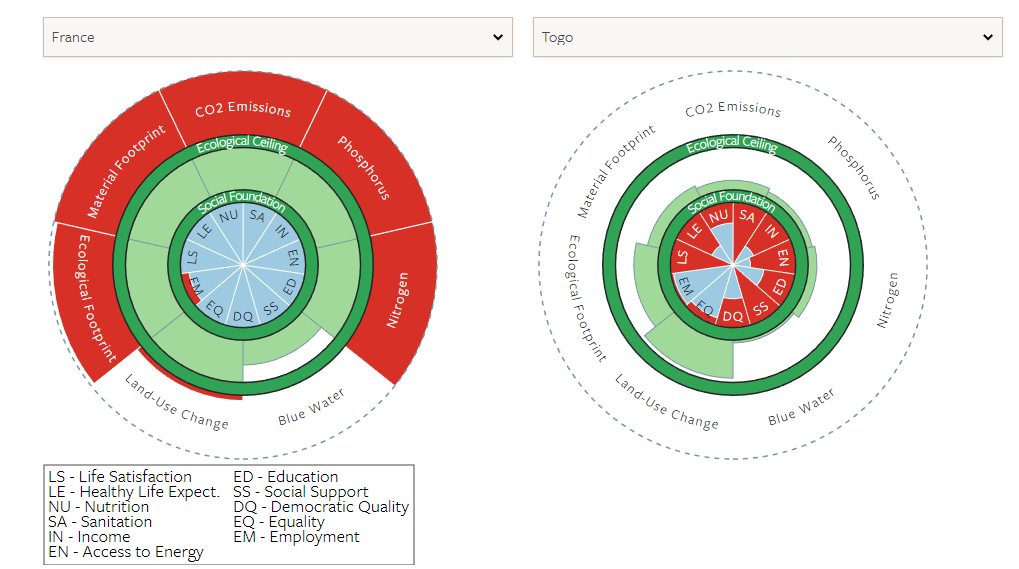

The doughnut offers a nifty way to connect two crucial aspects: our planet’s limits and the essential needs of us humans. Picture it like this: the outer circle represents those nine planetary boundaries we mustn’t cross, while the inner circle symbolizes the basic needs we all share. To break it down a bit more, experts worldwide have typically used the Stockholm Resilience Centre‘s models to figure out those planetary boundaries. And for our human needs, they’ve turned to indicators tied to the Sustainable Development Goals (you know, those significant global objectives that have been agreed upon internationally). Now, that space right in between the two circles? That’s where humanity can thrive, safely and fairly.

The doughnut concept has been put into action on various scales. Nationally, it’s been embraced through initiatives like “A good Life for All Within Planetary Boundaries.” And on a local level, more than thirty places worldwide, from Brussels to Amsterdam<, Geneva to Nanaimo, and Grenoble to Frankfurt, have taken up the doughnut challenge. What’s so great about this compass is that it speaks to everyone, whether you’re part of a public or private organization. In fact, some forward-thinking private companies in Brussels and Amsterdam are experimenting with it to reevaluate their purpose, how they’re run, their networks, finances, and even ownership structures.

The doughnut concept isn’t just a theoretical framework; it’s a call to action. Local communities are getting in on the action too, using a brilliant tool called the “doughnut deal,” championed by Anne Stikjel, to spark collaborative efforts that drive real change right in their own neighborhoods.

All countries in the red

The doughnut visualization enables us to gauge the extent to which a society surpasses either its social ceiling or floor, depending on the chosen set of indicators (which may vary at different geographical levels). When considering the doughnut framework, all countries are currently found in the red zone, indicating the need for improvements across various dimensions.

Source : https://goodlife.leeds.ac.uk/

Countries in the Northern hemisphere, including France, often exceed several ecological limits due to excessive resource consumption. However, they appear to be relatively successful in meeting the social needs of their populations. In contrast, Southern countries like Togo have a more favorable environmental impact but struggle with significant challenges related to social sustainability.

While the doughnut framework is praiseworthy for its ability to visually represent regional trends in addressing human needs, it only partially addresses the fundamental question posed by Bhutan: “What is enough?” This framework may overlook the plight of the most marginalized individuals by relying on averages (for some indicators). Additionally, it provides limited insights into its counterpart question, “What is too much?”

Galloping inequality

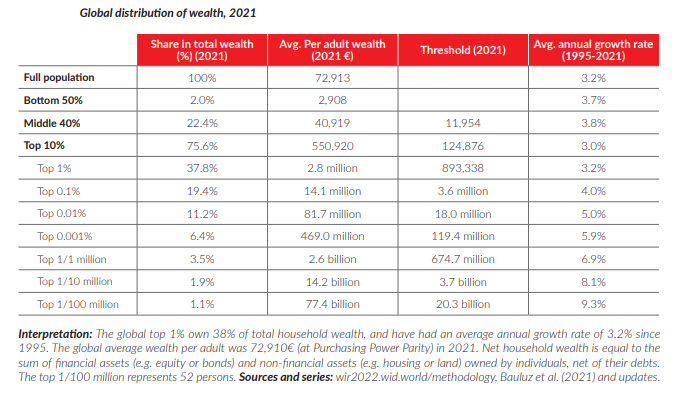

The income growth over the past couple of decades tells a powerful story about global inequality. Between 1995 and 2021, the annual wealth of the entire world population increased at an average rate of 3.2%. However, if we focus on the top 0.000001%, the wealthiest of the wealthy, their wealth skyrocketed at an average annual rate of 9.3%. In simpler terms, as the table below illustrates, the richer you were to begin with, the faster your wealth has been growing from 1995 to 2021.

Source: WID (2022, p. 90)

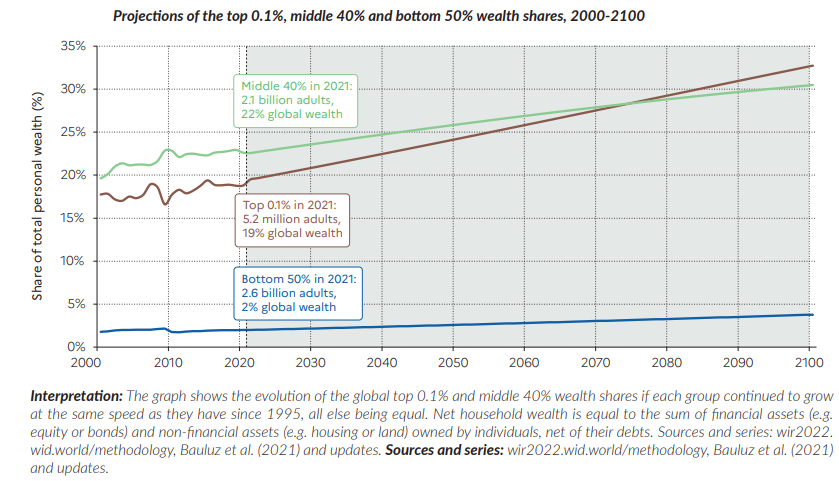

If income and wealth continue to grow at this pace, data from the World Inequality Database (WID) paints a concerning picture. By 2050, the wealthiest 0.1%—that’s about 5.2 million adults—will possess over 30% of the world’s wealth, while the poorest 50%, roughly 2.6 billion people, will still hold less than 5%.

Source : WID (2022, p. 96)

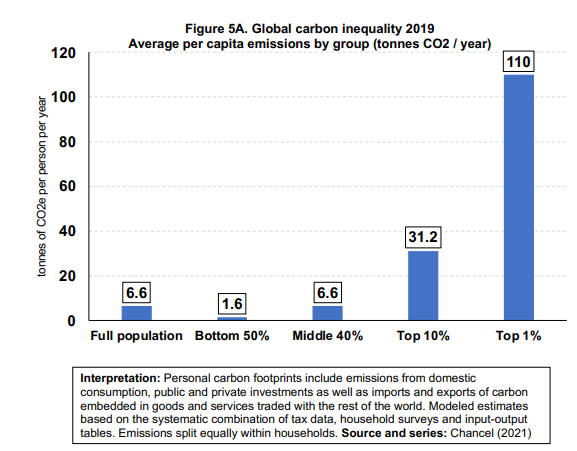

When it comes to environmental impact, a look at carbon footprints tells quite a story. On average, the top 1% of earners have a carbon footprint of a whopping 110 tonnes of CO2 per year, while the least affluent 50% of the population clocks in at a much more modest 1.6 tonnes.

Source: WID (2022) Climate Change & the Global Inequality of Carbon Emissions (1990-2020)

Environmental excesses linked to social excesses

This prompts important questions about the steps taken by government authorities to adhere to global boundaries. It also calls into question the international, national, and local rules put in place to curb the growth of inequality through various means, such as overseeing and limiting financial markets, taxation policies, and bans, among others.

But here’s where it gets really interesting: the challenge ahead isn’t just about striking a balance between meeting social needs and addressing environmental concerns. It’s also about reevaluating the environmental limits, taking into account the social excesses. These discussions need to be held collectively.

So, when we talk about questioning these limits, it’s about collectively establishing priorities from a socio-economic standpoint. It involves making a clear distinction, especially between what we call the “foundational economy” and the “non-foundational economy.” The foundational economy covers goods and services that everyone needs, regardless of their income or status, supporting our everyday lives.

But this isn’t just about ensuring that basic needs are met; it’s also about considering human limitations and recognizing our physical and social boundaries. In simpler terms, it’s about addressing various forms of social excess, whether it’s excessive consumption, long working hours, or harnessing emotions for productivity.

In this regard, participatory approaches based on locally developed social indicators can provide valuable insights for reflection.

Systemic dynamics of the crisis of capitalism

Putting the doughnut concept into action presents a significant challenge: it’s not merely about juxtaposing social and environmental indicators side by side. Doing so would oversimplify the social aspect, often reducing it to just basic needs, and missing the complex dynamics at play within the doughnut model. These dynamics are closely entwined with our prevailing economic system, capitalism, which erodes the conditions necessary for good life.

So, what’s truly fascinating and vital is to grasp what’s unfolding right at the heart of the doughnut and the intricate dynamics that connect environmental and social boundaries. Think of it as delving into the intertwined political and cultural histories of both nature and humanity, much like what Paul Guillibert highlights in “Terre et capital. Pour un communisme du vivant.”

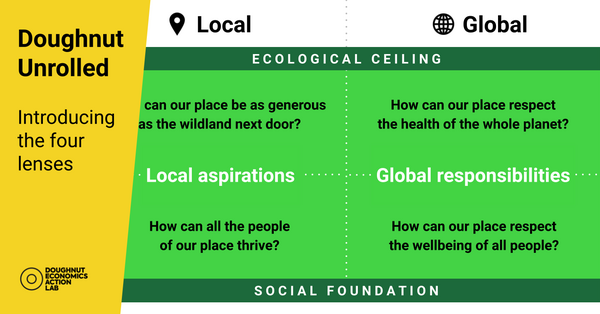

Consequently, the countries of the North are not simply over-exploiting nature on the scale of their territory, while at the same time meeting the relative needs of their population: their development model involves the joint exploitation of people here and elsewhere, of the living and the non-living on a global scale. This integration of the global into the local, while worked out through the four lenses of the doughnut, has yet to be materialised at the heart of the doughnut’s formalisation in order to integrate planetary limits in a systemic way combined with human and social limits.

Source : Doughnut Economics Action Lab

In this way, the doughnut should serve as an opportunity for the groups that embrace it to fully reconsider the limits of nature (including our own) and move beyond a technical approach to address these limits. Instead, it encourages shared discussions about setting social minimums and maximums. Embracing these limits requires the implementation of robust regulations, aiming to not only improve the conditions of the less fortunate but also, and most importantly, to rein in the excesses of the more privileged.

Some references:

Delahais, T., Ottaviani, F., Berthaud, A. & Clot, H. (2023), Bridging the gap between wellbeing and evaluation : Lessons from IBEST, a french experience, Evaluation and Program planning, 97.

Ottaviani F., Steiler D., 2022. Economic peace as a counterpoint to the warfare economy: Rethinking individual and collective responsibility, Journal of Business Ethics (The), 177, 1 : pages 19–29.

Ottaviani, F., Le Roy, A. & O’Sullivan, P. (2021), (2021), Constructing Non-monetary Social Indicators: An Analysis of the Effects of Interpretive Communities (2021), Ecological Economics, 183, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2021.106962.

Ottaviani, F. (2018), Time in the development of indicators on sustainable well-being: a local experiment in developing alternative indicators (2018), Social Indicators Research, 135(1), p. 53-73.