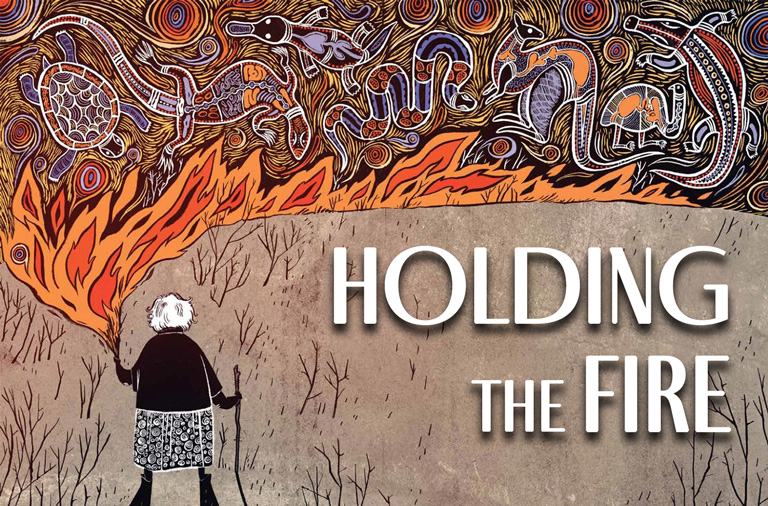

Welcome to Holding the Fire: Indigenous Voices on the Great Unraveling.

This podcast is about bringing forward the perspectives of Indigenous communities from around the world, as all of us, humans and more than humans alike, reckon with the consequences of a global, industrial society built on growth, extraction, and colonialism.

A long, winding path has led me to hosting this podcast.

Like many people, I have been horrified, outraged, and heart broken repeatedly by what is happening in the world.

My path began when I watched the government of the United States invade and destroy the country of Iraq, basing a war on what had already been shown in advance to be lies and propaganda. Outraged by the actions of the government and corporate media in the country where I live, I threw myself onto the frontlines of the occupation in Iraq so I could see what was happening with my own eyes. My initial trip to Baghdad unfolded into a decade of war reporting. The bodies of women and small children killed in Fallujah haunt me to this day. I believed, albeit naively, that I could help end an occupation that killed more than one million Iraqis.

Another marker on the path that led me here was the BP oil disaster in the Gulf of Mexico. Growing up in Houston, some of my fondest childhood memories were with my grandparents on the coast of Galveston. To this day, I have vivid memories of walking on the beach with them while we looked for sharks teeth and seashells, as well as swimming in the surf. So when BP negligently released millions of gallons of oil into that ecosystem, I took it personally. I spent years reporting on what became the single largest man-made disaster in U.S. history-filing dozens of stories about untold numbers of dead marine animals, birds, other wildlife, and humans that were killed, and continue to die, from BP’s chemicals. I thought my work would help bring justice to BP, and a corporate controlled government that allowed this to happen. Again, like with Iraq, I was devastated that this did not come to pass, and left simmering in my own anger.

Feeling obliged to continue to do what I could, my reporting then transitioned into the global climate crisis, which I covered extensively for another decade, culminating in my book The End of Ice: Bearing Witness and Finding Meaning in the Path of Climate Disruption. Research for that book took me to some far flung places, from visiting with the late Dr Thomas Lovejoy in Camp 41 deep in the Amazon Rainforest, to floating above a bleaching Great Barrier Reef in Australia, to camping atop receding glaciers in the Alaska Range, and to Miami Beach, a city that will more than likely be underwater before the end of the century. My hope was that by showing people how far along we already are in the climate crisis, they would react accordingly, and governments would be forced to do the right thing and begin an emergency response to mitigate and adapt to the crisis. But four years after the publication of that book, the crisis continues to accelerate far beyond the worst-case projections.

All of these experiences led me into deep grief; rage, frustration, depression, sadness, and despair became constant companions. My friend Joanna Macy, author, Eco philosopher, and teacher of The Work That Reconnects, calls the collapse of this unsustainable way of life and all the suffering that comes with it, The Great Unraveling. She also points out how this unraveling precedes The Great Turning, which will be a vital, creative response, and a wholesale revisioning of our values and perceptions towards the Earth.

Through this journey, I came to see that those in power are incapable or unwilling of moving away from our current course, where the destruction of nature, the pursuit of resources and profit, and the disregard for life is leading us to ruin. We would have to look elsewhere for guidance and leadership.

Amidst all of this, a dear friend of mine, Stan Rushworth, suggested we talk with Indigenous people. Given that Indigenous populations around the world have been experiencing collapse, genocide, erasure, and racism, among other traumas, for millennia, his suggestion made perfect sense. That idea led us to co-edit a book titled We Are the Middle of Forever, where we interviewed 20 Indigenous persons. While working on that book, I settled into a new sense of calm – and I developed a deeper sense of purpose – as I began to understand and adopt Indigenous values. I listened to people who had been through the complete collapse of their worlds – but who were also continuing to do great work. They didn’t have false hope. They knew better than anyone what was being done to the planet and to people on the margins of society. Yet here they were, leading the way through our current poly-crisis in a calm, dignified, reverent way, simply by living by Indigenous values as they always had.

I had little idea how desperate I had become for this entirely different perspective, not just on what’s happening in the world, but on life itself.

Stan and I hoped our book would bring the same sense of calm and purpose we felt while working on it, to those who would read it. And that has certainly been the feedback we’ve received.

While Stan and I focused on Turtle Island, this podcast spans the globe, as what we face is a global crisis. So our team set out to hear voices from every continent. It has been my honor and privilege to speak with, and most importantly, to listen to these remarkable people.

Several common themes emerged from our conversations, ranging from deep connection with Earth, to the horrific impacts of colonization, to resilience in the face of suffering.

Dr Anne Poelina from Australia had this to say about getting back to valuing what is most important for all of us.

What we’re saying as Indigenous people, not just in my country, but around the world where we’ve held onto these last bastions of biodiversity – we’re saying, “This is the lifeblood of the planet. These last places that we have protected and held onto, under much pressure, strife, continual invasion and unjust development – we really need to look at how do we change the value and realize that it is nature that sustains our wellbeing, nature that gives us the oxygen, nature that creates the rivers of life, nature that creates all of those things in abundance that we need to sustain ourselves as human beings on this planet.

Anne also reminds us of the critical importance of listening to Indigenous people at this moment in history.

What we must do is come together, and stop discounting the ancient wisdom of indigenous people, first people or First Nations people across the globe, because we have lived with the Anthropocene in the past, particularly in my country. And we have shaped that. So we were living always in a symbiotic relationship. So what we’re saying is that Western thinking Western thought, top down leadership and governance which has become toxic, must have a pause, must listen to this ancient wisdom, because this is the ancient wisdom that can teach us how to see and be in the world a different way.

Aslak Holmberg, an Indigenous Saami who lives on the Deatnu River, on the border of Norway and Finland, offers his perspective on how we’ve arrived at a global crisis.

I think this is the clear result of an ideology that is already from the start that is doomed to fail. Because if you build something on unsustainability then it will crash at one point and we are at that point when ecosystems are crashing and the whole global climate is starting to collapse.

Given these insights, I was hoping to learn more about how Indigenous people are dealing with the grief and trauma from all they have lived through, yet still managing to live from their heart.

It was this question that led me to Galina Angarove from the Lake Baikal region of Siberia.

Understanding the human condition, understanding suffering, knowing our place on this beautiful and fragile planet, having our hearts broken, hurting, grieving, healing, and always, always having hope that we can overcome and thrive. It’s all of it. This is why we’re here. How can I be the best version of myself given the story I was born with and lift and what can I do with it? It’s living the best way that I can, allowing life to happen to me, guided by my heart, caring for others leaving behind something important, after I’m long gone, and that’s how I tried to live those values that came from my grand sisters, my grandmother. And that’s what the land has been teaching us all along.

It is also refreshing to hear folks discuss the disparity between their traditional ways of life compared to so-called modern society. Celine Lim, an Indigenous Kayan from the Baram area in Sarawak, Malaysia spoke to this.

Contemporary society tells me the more I consume, the happier I am, but when I go back into the communities, the more that we give back or the more that we replenish, and when we allow ourselves to actually live according to a flow, that is when you are the happiest when you find yourself being a part of a whole.

I also hoped to hear more from those who have a deep connection to their native lands, and every single person I spoke with shared beautiful stories. Here is Sam Olando of the Luo people of Kenya, a Human Rights Defender and a community organizer, speaking to this.

In my community, land is the basis of identity, which means your identity and it gives you a home, that land. We connect land with our ancestors. If this is where I buried my forefathers then I’ve got a special attachment to it. So that when you are doing compensation when you’re doing, maybe infrastructure development programs, then compensation can not only be in terms of monetary compensation, but also must pay attention to the social attachment that I have to my piece of land.

I’ve become fascinated by these deeper connections to the Earth, because as we heard earlier, it’s our disconnection that is the root cause of so many problems we face today. Paty Gualinga, an Indigenous rights defender and foreign relations leader of the Kichwa People of Sarayaku in the Ecuadorian Amazon, highlighted the importance of connecting to the places we live.

My father was a shaman. And he was always saying that we have different parts, different ways. But there is one spirit that connects everybody. All the spirituality is just one. But we can arrive from different parts, different religions, different things, different beliefs, but we are connected in the big thing together. The Sarayaku people recognize that the forest, the jungle, the Amazonia, it’s alive. The Amazonia it’s alive. And we need to respect that that the Amazonia feels. You know, the trees, the animals that it’s something that it’s alive. And there are these protectors, like they’re not like real persons, but they are just like these energies that protect the forests. They recognize that they have these protectors around. It’s connected to the earth. And it’s what they believe. And it’s what they protect. It’s just like they’re protecting people because Amazonia it’s still alive. It’s just like it’s different. No it’s not that they are trees, their stones they’re not. It’s protecting life together with that, and it’s about what they believe and they have this Cosmo-vision to protect the Earth.

It is also important to remember that Indigenous populations around the globe have borne the brunt of the suffering caused by colonialism and imperialism. In the case of Alson Kelen and the Indigenous people of the Marshall Islands, after surviving massive nuclear weapons testing where they live, now they are facing yet another existential threat-the climate crisis.

Now, for us, we don’t just get sick, we lost our identity, we lost our land, we lost a culture that was given to us by God. So we’re living in a place where practically we cannot survive for a long time. And I always tell people, that nuclear testing, we sacrifice, we sacrifice our life our, land our culture, for the good of mankind, to bring peace to the world. And now, the next thing in line is climate change, which will relocate us from our country. First, a nuclear testing relocated us from our islands. But next is climate change will relocate us from our country.

Indigenous people have survived the aforementioned onslaughts by continuing to serve out of a deep sense of belonging and responsibility, rather than focussing on their rights. In this sacred yet pragmatic way, Shoba Liban, of the Boorana tribe in northern Kenya, provides a living example of this, for all of us.

Hoping for the best is not good enough for me like what I believe in. I should do whatever I believe I want to do, I want to continue doing. Like I said, if I can’t do it today, I’ll do it tomorrow, but I make sure I have planned everything that I want to accomplish. I continue doing it until I see success at times. I also wonder how I managed to do that. But I think it is being focused and believing in yourself that also help. So whoever has a problem, because even in Africa, right now, there are a lot of challenges in terms of mental health. There are a lot of unemployment, like a cost of living is very high. Others are even taking their lives. But if you talk to each other, you have networks, you talk over the radio, local radios, you visit each other. Like for example in our case, you cannot miss to go to people’s funeral. If you are around that area, in marriage, we support each other. So at least that kind of thing has supported how we manage our crisis.

All of this leads us to finding a way to be in this world, not just as a means of survival, but something far deeper than that-how to find true belonging, and true community, with both humans and the more-than-human world. For it is only when we are part of a vibrant reciprocal community of like-minded and like-hearted kin are we able to be of the most service. Only then, are we able to have the commitment necessary to serve the planet during this time of the great unraveling.

This topic coincides with Dr Yuria Celidwin’s lifelong focus. Yuria, a native of Nahua and Maya descent from Chiapas, Mexico, conducts research that combines the vibrant threads of Indigenous studies, cultural psychology, and contemplative science.

We need commitment, we need community. We need to create spaces of trust. But for that, you know, there’s tremendous work that we need to be doing. But I don’t think that any of that work will be possible. Should we not have that commitment, that commitment that no matter how challenging and tremendously difficult it will be to reckon with these narratives and to dismantle these narratives because you know, seeing the horror in the eye of all these narratives that we live by comes with tremendous understanding. It will leave us very fragile, very vulnerable and most of course are not willing to do them because we don’t feel safe but if we are able to stand the heat and create this basis if we commit to do this kind of work for the benefit of the planet then we may able to learn that we can fly.

Then we are faced with the challenge of maintaining perspective on the polycrisis. How do we do this, given the relentless nature of bad news on all fronts: pain, suffering, and death are everywhere one looks, and things only continue to worsen.

Lyla June Johnston, a woman of Navajo, Cheyenne and European lineages who lives in New Mexico offers a perspective that changes the entire paradigm of our current predicament:

The polycrisis, and the convergence of crises in the collapse that we are learning about and experiencing, that crisis happened a long time ago. Actually, it’s manifesting now. But this crisis has been going on since 1492. Right, for example, are we reaping what we’ve sown, you know, maybe the collapse is fruiting now? But didn’t we plant it a long time ago? And why are we so shocked that this is happening? Right? We’ve been saying this for centuries, you know, it’s almost like creator was giving us nine lives, you know, it’s like, we were acting a fool. And he was patient and like, Okay, well, let me give you another chance. And we did it again, and again, and again, kept brutalizing each other, kept brutalizing the earth, and the earth can only take so much. I mean, the fact that she’s even lasted this long, is incredible, with the amount of brutality and the amount of abuse, but she’s very resilient, she can actually absorb a lot of abuse, she can handle a lot of insanity. But only to a certain point, you know, and at a certain point, we can’t go on like this. And so in that sense, to me, the collapse has, is almost like overdue, you know, like, the crisis started a long time ago. And if, if this is what it takes to sit our butts down and be like, No, you cannot do this anymore. Period, find another way. And if you don’t, I’m gonna force you to, if that’s what it takes, then so be it because we’ve been having a ball just being extremely disrespectful to her and to each other, and with no consequences whatsoever. And so, in that sense, it’s not such a radical reframing at all. It’s almost like a no brainer, like what did we expect, you know, extracting her, treating her like a slave, you know, treating the soil like it’s, it’s just here for our benefit.

Having had the opportunity to speak with each of these remarkable people, the fundamental way I perceive, feel, and experience the Great Unraveling has been changed.

Hosting this podcast has been a journey of heart and mind, one that has taken me deeper in both understanding and feeling what these times are asking from us.

I trust that by listening with your heart, you will have a similar experience.

As the Great Unraveling deepens, we need as many people as possible to wake from the false, destructive dream of infinite growth and techno-utopian progress and embrace a different, deeper way of knowing and being. The voices we’ve featured on Holding the Fire are pointing humanity back to our collective heart. Our hope is that after listening to these amazing people, you will be moved to join in creating the different future we need.