This article first appeared on the ARC2020 website. ARC2020 is a platform for agri-food and rural actors working towards better food, farming, and rural policies for Europe.

“As many key competencies relating to consumption-side policies fall under national competence, the SFS Law should require action at national and local level through National Sustainable Food Plans.”

EU Food Policy Coalition

Among the issues to be addressed at the national level: the regulation of agricultural land, over which only Member States have jurisdiction.

Marie-Lise Breure-Montagne offers an analysis of land access in France and Germany for the Rural Resilience project.

Special thanks to Magali Bardou, and to Coline Sovran of Terre de Liens, for their comments and inputs on this analysis.

How to distribute agricultural land for more resilient agriculture… without Europe-wide legislation?

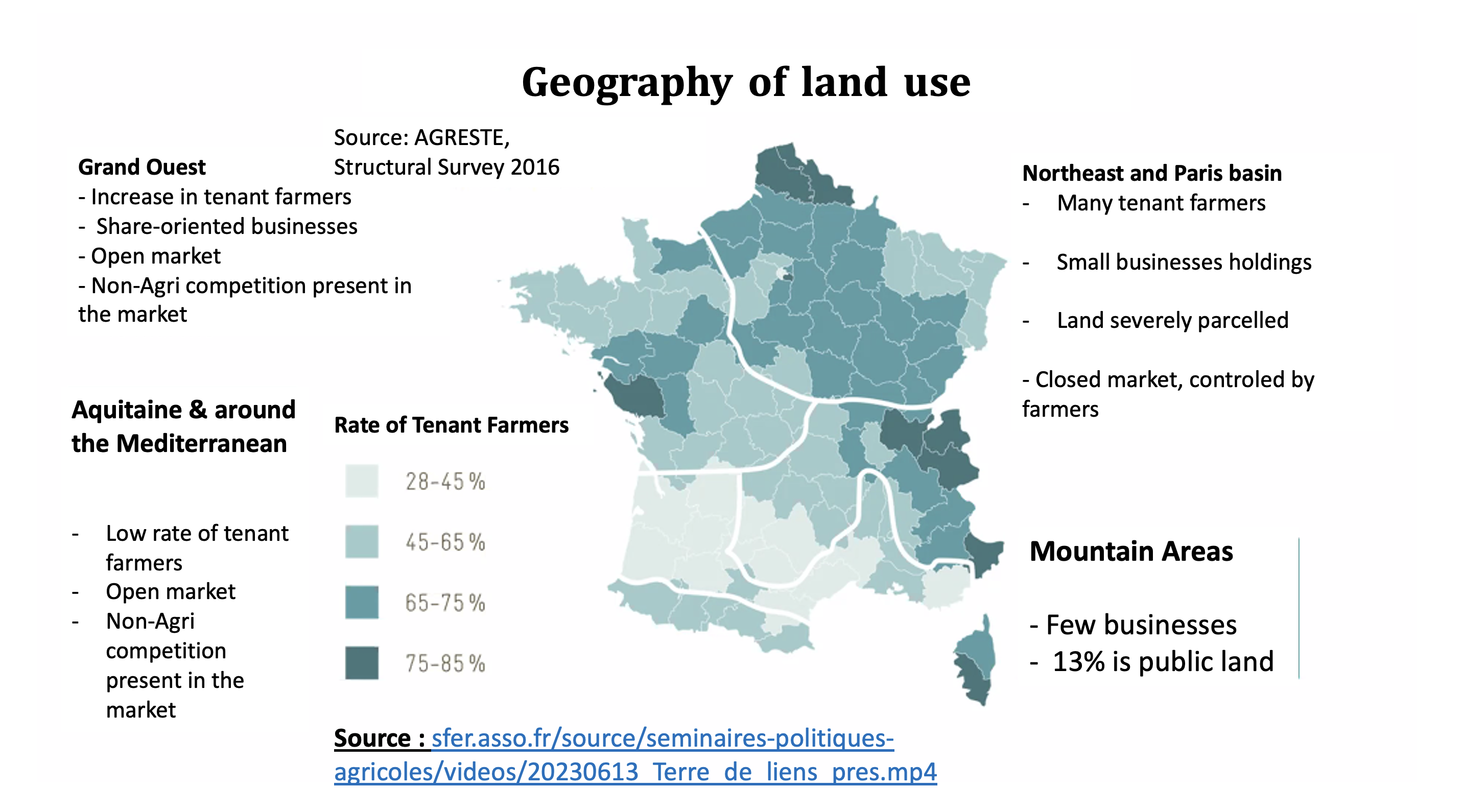

It is impossible to focus on the re-territorialisation of food systems without looking at how urban communities access agricultural land in rural areas. One example might be “developing existing market gardening activities to supply organic fruits and vegetables to the city’s nurseries.” In France, public entities now account for only 5% of agricultural land area, with this figure rising to 13% in the south of the country and mountainous areas (source: Terre de Liens / CEREMA).

Another category of actors calling for their share of land: new entrants. “Rural areas are emptying, while young and new entrants that would like to settle in a farming activity, and notably those following an agroecological approach, struggle to access land.” In France, the NIMA (Non Issues des Milieux Agricoles, or farmers from non-farming backgrounds) are young (ish) back-to-the-landers that have not inherited land or taken over a farm from their parents. In France, NIMAs constitute a major rural phenomenon. They represent 60% of potential new farmers (Source: Chambre d’agriculture France, 2020).

New actors find themselves in a particularly complex land regulation system that pre-dates the CAP. What trajectories do these new entrants have in France and Germany, in the context of the shared and individual histories of each country?

Agricultural land is subject to a striking economic paradox: an essential factor in agricultural production, but outside the scope of European public policies (agricultural or environmental). We are at the beginning of a decade where generational renewal among farmers is endangering large parts of European agriculture. Some instruments, such as the right of pre-emption, have served as the basis for proposals to build a European land policy from scratch. This right, being a small common denominator between France and Germany, deserves our full attention. In France, one facet is the right of pre-emption enjoyed by tenant farmers; in other cases, regional development agencies (SAFERs, Sociétés d’aménagement foncier et d’établissement rural) and local authorities also exercise this right of pre-emption.

Continuing the comparison between these two giants of Europe, we will see in part 2 to what extent in each country the regional level is autonomous and relevant for adapting land policies to more local realities. And finally, because civil society remains one of the drivers of the agroecological transition, it falls on citizen initiatives to put land on the agenda.

Photo courtesy of Christian Lue / Unsplash

I. Legislative framework pre-dates the CAP

The land regulation is outdated: it was designed in the 1950s. At that time, French government experts considered the peasant-farmer population to be twice too numerous. In addition, as Minister Edgar PISANI explained during the 1962 modernisation law, this legislation pushes farmers to acquire ownership of the land they cultivate. “This reflects a very patrimonial vision of agricultural land in France, despite the implementation of tenant farming [law of 1946, limiting abuses by land owners], which secures tenant farmers,” says Coline Sovran (Terre de Liens). In each department, a dedicated Commission (Cumuls et réunions d’exploitation agricole) determines minimum and maximum surfaces by natural regions, according to categories of land and the nature of crops.

Above all, the essential instrument of this policy is constituted by the SAFER agencies whose “purpose is to improve agrarian structures, increase the surface area of certain farms and facilitate the cultivation of land and the installation of farmers on the land,” according to Histoire de la France Rurale (Tome 4, 1987, Duby & Wallon). The SAFER is an instrument for controlling the land market “in order to promote a more judicious distribution of land put up for sale.” SAFERs are semi-public anonymous companies that “have a pre-emptive right to carry out acquisitions and operate on a non-profit basis”. They are also aligned with the principle of co-management of French agriculture: “the initiative to establish SAFERs does not belong to the State or public authorities [which can also exercise a pre-emptive right], but to professional organisations considered representative”.

The Confederation Paysanne, which developed from the 1970s-1980s onwards and remains a “minority union”, continues to fight for equitable governance of the SAFER agencies:

“After hearing the candidates, all members of the [local] commission must participate in the debates. In the event of a vote, each union has one vote, regardless of the number of delegates present. The minutes containing the commission’s proposals must be signed by all. A step towards pluralism and transparency!”

A turning point occurred at the beginning of this century: “In France, the ‘agricultural structure policy’ (more on this in part 2), designed in 1960 as a framework for the land market, with the SAFERs, and the evolution of agricultural holdings, by departmental structure committees, no longer serves as a framework for the evolution of the business structures of holdings, because the transfer of [asset] shares of agricultural companies is no longer subject to authorisation since 2006. It’s the same situation in Germany: transfers of [asset] shares of agricultural companies are not subject to authorisation, unlike sales and leases of land”. In France, it wasn’t until the Sempastous law came into effect on April 1, 2023 that the requirement of prior approval from the Prefecture was introduced for certain share transfers. Time will tell how the law will be applied and will affect this very opaque and very significant part of the agricultural land market.

As already shown by the Hands on the Land study in 2013, land take (artificialisation) is a chronic disease. In France, the decrease in agricultural land or land take appears to be equivalent to the surface area of a department every 10 years between 1992 and 2003, then every 7 years between 2006 and 2009, etc. “One fifth of French agricultural potential will have been lost between 1960 and 2060,” summarises the National Federation of SAFERs. Whose problem is it to solve? At the moment, it is assigned to various urban planning policies (carried out locally by the authorities, defined by national laws). The principle of economical land management, established in 2000 by the Solidarity and Urban Renewal law (SRU) has been gradually refined with “the multiplication of land management tools, such as reinforced agriculture protection zoning (ZAP – Zonages de protection renforcée de l’agriculture); Perimeters of protection and enhancement of peri-urban agricultural and natural areas (PAEN).” The more recent establishment of the Zero Net Land Take (ZAN) objective, following the Citizen Conference for the Climate and then the Climate and Resilience law of August 22, 2021, raises a new hope. But it’s been quickly tempered by agricultural land experts in France: “By the time ZAN is visible on the ground, a great inertia [regarding mere coordination between urban planning and land actions] is to be feared.” In addition, the value of land zoned for construction in France is on average 25 times higher than agricultural land (Source: FNSAFER, The price of land in 2022). In some areas, the value is up to 500 times higher. It’s an equation that’s almost impossible to fight. Finally, another powerful factor of inertia in a period of declining public budgets: A municipality that builds and ‘develops’ its territory is a municipality that will be able to collect better tax revenues. The France of the ‘builder-mayors’, a legacy of the post-war glory days, is alive and well.

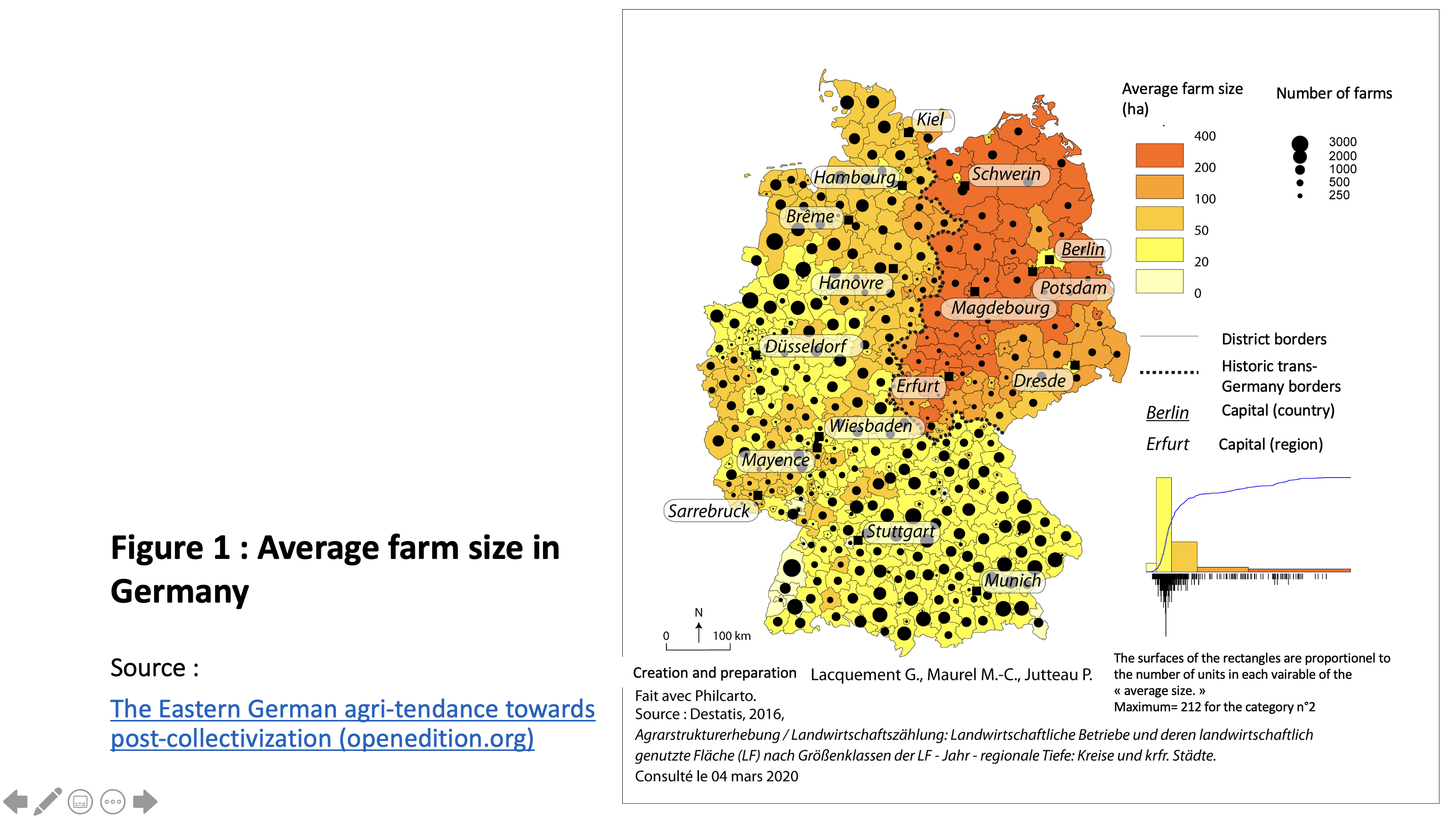

Figure 1: Average farm size in Germany. Source: Lacquement, Maurel & Jutteau (2019)

Figure 1: Average farm size in Germany. Source: Lacquement, Maurel & Jutteau (2019)

In Germany, a country more densely populated than France, what needs to be especially noted about its agricultural land policy is the exceptional way it has developed since reunification.

To summarise the situation in West Germany, the Land Parcel Act came into force almost at the same time as in France, on July 28, 1961. Minor modifications were introduced in 1974 and 1986 (and after reunification: in 2005, 2006 and 2008).

In former East Germany, de-collectivisation resulted in land grabbing in several stages:

“[The 1991 Agricultural Adaptation Law] restored full property rights over assets formerly transferred to the cooperative (under forced collectivization of agriculture). At the same time, the organisation responsible for privatising the assets of the people of the former GDR proceeded to restore confiscated assets, with the exception of the lands of the former large estates confiscated by agrarian reform.“

The map of German agricultural structures shows a clear difference between East and West Germany: very large farms have emerged in the East (see Figure 1). Another direct consequence, still prevalent today: “The fragmentation of land ownership and its separation from its use, are at the origin of the predominant position of the rental market.”

75% of German land is indirectly farmed (leased), which is 10 points higher than in France (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Geography of Land Use in France. Source : SFER

II. Right to pre-emption

The right to pre-emption is a Franco-German exception. Could it be the centrepiece of a European land directive? In March 2023, a debate organised by ECVC discussed the interest of the right of pre-emption as a structuring instrument for a future “land directive for the EU”.

In Germany,

“the right of pre-emption can be exercised by non-profit associations (‘Landgesellschaften’). Their legal basis dates back to 1919 (‘Reichssiedlungsgesetz’) […] In Baden-Württemberg, the rural development company, based on the 2010 law on the improvement of agricultural structures, can also exercise pre-emption rights for the benefit of its land bank, without having an immediate second buyer. The land must then be used to improve agricultural structures over a period of 10 years.”

In France, pre-emption rights are defined and exercised as follows:

“A right conferred on a person, by law or by contract, to acquire property by preference to another […] In France, this right is only provided for in special legislations [tenant farming status, for instance]. According to the French rural code, the right of pre-emption is the right of the tenant farmer to be informed by the owner of his intention to sell and to have preference over any other potential buyer in case of sale of the property.”

The tenant farmer cannot exercise this right in the event of sale to a family member, exchange, or expropriation in the public interest. Local authorities can thus pre-empt land, in the majority of cases to urbanise it, as they enjoy the right of pre-emption for planning, once permitted by the Urban Plans’ zoning. Finally, the right of pre-emption can only apply to the sale of rural land, of a minimum size, with justification for the proposed use.

While sometimes presented as a good approach for a future European directive on agricultural land, we should keep in mind the history of the right of pre-emption in France, according to Duby and Wallon (1987):

“Two decisions of the Court of Cassation, dated November 25, 1975, practically strip exercising the right of pre-emption of any power. Indeed, it can no longer be exercised whenever the transaction concerns a balanced or judiciously composed exploitation.”

In other words, through jurisprudence, the judge introduces a notion neutralising the legislator’s vision. Finally, historians believe that “the framework laws […] simply inflected the line of the slope by accentuating the process of eliminating the smallest producers”, and conclude by affirming that

“large farms have suffered little from the theoretical barriers [including the right of pre-emption] erected to block their expansion.”

More current data show that the right of pre-emption exercised by SAFER remains marginal:

“In 2021, SAFER exercised 3,040 pre-emptions. In 57% of cases, pre-emption led to an acquisition; in 43%, a withdrawal from the sale, as permitted by the rural code […]. Compared to all SAFER activities, this represents 13% of the number of acquisitions, 7% of the area and 3% of their value.”

It is no surprise to learn that the right of pre-emption is a fairly complex legal instrument:

“The rules governing the exercise of the right of pre-emption have the particularity that they partly fall under public law [land and planning policy] and partly under private law [including property law]. The litigation of pre-emption is therefore shared between two types of jurisdiction, with all the dysfunctional risks that such a situation implies.”

Concerning this right, the European Convention on Human Rights (to which all national laws of Member States must conform) can be read as follows:

“It should be emphasised, […] concerning the litigation relating to the consequences of the annulment of the pre-emption decision, that the distribution of competences in this matter remains difficult to understand.”

And that

“it is not certain, however, that the transformations thus observed [via the law on Responsible Planning] are sufficient to protect France from condemnation by Strasbourg.”

In short, at present, there are many (too many?) obstacles in sight before a structuring instrument such as the right to pre-emption can be rolled out at European level.

Rendez-vous shortly for part 2 of this analysis: to what extent, France and Germany, is the regional level autonomous and relevant for adapting land policies to more local realities? And what lessons can be learned from civil society initiatives?

In 2023-2024, the Rural Resilience project embarks on a new phase of joining the policy dots while continuing to nurture what we have built together, and widening the lens from France to Germany and the broader Europe. To learn more, visit the project page, and follow ARC2020 on LinkedIn, Twitter, Facebook or Instagram.