This article first appeared on the ARC2020 website. ARC2020 is a platform for agri-food and rural actors working towards better food, farming, and rural policies for Europe.

We’re back on Chiara Garini’s farm at the foot of the Italian Alps, where the forest garden is in beautiful shape in its fifth mushroom season. Running the farm is a constant balancing act. It’s the satisfaction of producing food that keeps Chiara going: despite the time suck of bureaucratic burdens, she is harvesting herbs, fruits and berries as well as shiitakes, and excitingly, producing jams and preserves on the farm.

In this letter, Chiara asks hard questions about the paradox of hiring a worker. Can you take on an employee before you have full security? How do you achieve that security without additional workforce?

Policy obstacles are another source of frustration. If the diversification of farm activities is a stated objective of the EU’s rural development plan, why are Chiara’s efforts to diversify at odds with this funding? Don’t miss our policy explainer at the end of this letter, where we examine the policy constraints that prevent Chiara and other small-scale farmers from valorising labour, quality food and biodiversity.

More than a year has passed since my last letter from the farm. It feels like yesterday. Yet looking around me I realize we have made much progress.

The forest garden field is starting to take a shape which I enjoy looking at. The fruit trees are growing, casting shade that refreshes me when I pass beneath them. We have started harvesting a decent amount of berries (currants, goumi, sea buckthorns) that we process into a mixed berry jam.

A closer view of the forest garden with perennial aromatic herbs growing with berry shrubs and fruit trees

We gave up on the idea of commercially producing fresh annual vegetables and expanded the perennial aromatic herb production which is more suited as a herbaceous layer of the forest garden, requires less labour and we can partially sell fresh to restaurants and for the remaining part dry and preserve for a whole year.

We are already in our fifth season of shiitake forest farming. We are still working in a small forest area that could be much better (easier water availability, more shade and humidity) but we have managed to improve our production methods and we are proudly harvesting dozens of kilos of mushrooms every week. Thanks to the use of non-woven fabric blankets we significantly reduce slug damage. We try to avoid the excessive drought and heat we experienced last summer by working on the microclimate around the fruiting logs: the fabric blankets reduce the drying out of soaked logs and can also be additionally soaked themselves in order to increase the humidity immediately around the logs.

Shiitake mushrooms growing abundantly with an improved production technique

What makes me proudest overall is that I finally see that we are producing food! That was our initial objective and we took the longer and more difficult path of agriculture. As prosaic as it might sound now, in the rare times when I stop for a second I realise we are creating foods starting from nothing, or better starting from some raw materials and natural elements.

In recent months we have been producing some new preserves in the lab. The fruit jams I mentioned, vegetable sauces using last year’s dried tomatoes, onions and eggplants, and two other products which allow us to make the most out of the whole shiitake production: a shiitake sauce made using the stems and lowest quality mushrooms, and a shiitake preserve made using too big or too small caps, chopped into pieces, roasted in the oven with extra virgin olive oil and immersed in water and lemon juice.

The stand at a local farmers’ market shared with a goat cheese farmer

We have started selling at the farmers’ market in our nearest city and collaborating with a local young farmer who raises goats in the forest. Even though bureaucratic constraints do not allow us to realise our dream of opening an on-farm restaurant or food truck, we are starting to offer farm visits where more people can come and experience first-hand our production systems and taste our food.

All of these have been a good boost of positive energy that we really needed to endure in this tiring and beautiful work!

Me harvesting mushrooms while wandering in quest of balance

In quest of balance

Often I feel I am wandering in quest of balance.

Compliance with legal and bureaucratic requirements, for me, is the right thing to do. However it can be very limiting. It is time and energy consuming, thus can become a very demotivating factor. I realised I was getting to a point where my main work focus was bureaucratic compliance and I was forgetting about what that compliance was for.

I know I cannot keep on asking myself and my body for such an amount of physical work for many more years, and I aim to delegate the operative work, although this is not an easy task. We do not have our employee any more due to personal reasons but it was a chance to reflect on paid labour. It may be too soon to hire someone until you do not have full financial security. But can you reach that security without sufficient workforce?

Presenting our new food products at a local fair

It is essential to remember free time and leisure, but sometimes a lot of work is needed to achieve results and it can be more stressful to impose free time on myself rather than just do what needs to be done and feel that satisfaction.

About satisfaction. As I said, we are making much progress, and I do feel satisfaction about that, but there’s a somewhat constant feeling of dissatisfaction that characterises our generation (or is it just me?!). It looks like we are all aiming for perfection but what we can do is just keep on trying and facing the errors and successes.

There are so many opposites among which I wander in search of an equilibrium, the right middle way. And I ask myself, is this wandering the motor of everything or is it all in vain?

Policy explainer

Chiara is making efforts to diversify her farming activities. What policy obstacles does she face, and why?

“The main issue I am facing is the over-complexity of laws in my province of Trento. The laws on farm multifunctionality make it very hard to diversify with new activities.

“In my region, on-farm restaurants are classified as ‘agritourism’. We are allowed to produce preserves in an agritourism kitchen, but not in our lab – even though it is compliant with all the food hygiene and safety regulations. Another example: you can serve farm food on outdoor tables, but it is not possible to have only outdoor tables.

“These unintelligible points are not even clearly stated in the law. People often say bureaucracy in Italy is too complex and demotivating and now I am starting to understand why!

“Furthermore the complexity of local laws makes the application of the EU Rural Development Plan very hard.

“As I mentioned in a previous letter even though I meet all the farm scale requirements and food hygiene and safety standards for opening an ‘agritourism’ (meaning cooking simple dishes with farm products) I cannot do it because I received RDP funding for the farm building, and that funding was for storing, processing and selling of farm products. So, according to the province, if I want to add another farm activity such as agritourism using the same building, I should give back the money I received, even though I would just add it to the activities that were financed. It is even more annoying when you look at the objectives of that RDP measure: diversification of farm activities, improvement of the farm’s economic performance, promotion of farm products through tourism – which is exactly what adding an agritourism would mean for our farm.”

Chiara is experiencing how narrower legal interpretations of the Italian 2006 framework law about agritourisms and its rendition and application at provincial level can become a rigid bureaucratic barricade that prevents the very essence of agricultural multifunctionality: the dynamic integration and valorisation of farm labour, assets, and outputs for the provision of food and public services in rural areas. While Art. 2, point 3(b) of the 2006 Italian framework law clearly establishes that agritourism activities can also include the selling of “food prepared by the farm”, and therefore also food processing as the case of Chiara, the provincial law is less explicit or clear about this possibility. In any case, the EU legal provisions regarding investments under the Rural Development Programmes or the recently approved CAP Strategic Plans are more general, and less prescriptive. Therefore, preventing public support towards the efforts to combine food processing and agritourism definitely has poor legal ground.

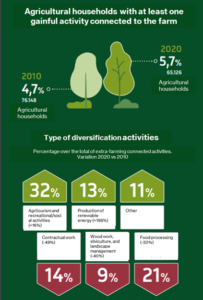

Click to expand the image. Source: ISTAT, adapted by Matteo Metta

Moreover, the focus on details, not only can it hinder the laudable actions on the ground, but also miss the bigger picture. For ten years, Italy continued to lose farmers engaged in farm income diversification like Chiara, especially in the area of on-farm food processing. Between 2010 and 2020, ISTAT reports that Italy lost 11,002 diversified farms (from 76,148 in 2010 to 65,126 in 2020). More worryingly, the quality of on-farm diversification is changing, probably worsening for agricultural multifunctionality. In Italy, the number of farms moving towards the production of renewable energy or the selling of farm accommodation is boosting. On the contrary, the number of farmers that are actually valorising farming labour and biodiversity by processing and selling directly their production – even through agritourism activities – is drastically decreasing.

This situation is probably resulting from a number of factors, ranging from the application of stricter food standards for small-scale farmers and the lack of support for their compliance, as well as the boom of financial incentives for so-called “farm modernisation” offered by the recent Italian governments under the European Recovery Fund or State Aid, such as the Parco Agrosolare.

Overall, failure of public authorities to accommodate multifunctional projects like those of Chiara can further exacerbate a larger trend in Italy towards a type of farm diversification that exploits capital and land, instead of valorising labour, quality food, and nature.