Is the word right on the tip of your tongue? You know, the word that sums up the ecological effects of more, faster and bigger vehicles, driving along more and wider lanes of roadway, throughout your region and all over the world?

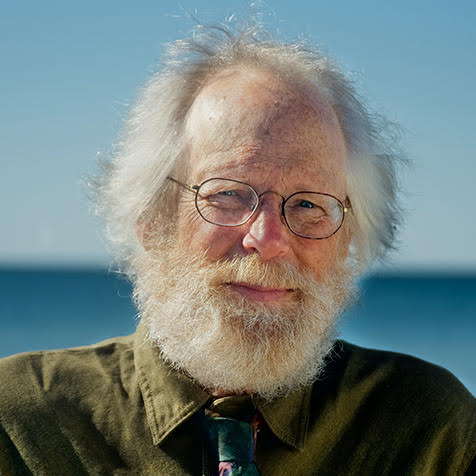

If the word “traffication” comes readily to mind, then you are likely familiar with the work of British scientist Paul Donald. After decades spent studying the decline of many animal species, he realized he – and we – need a simple term summarizing the manifold ways that road traffic impacts natural systems. So he invented the word which serves as the title of his important new book Traffication: How Cars Destroy Nature and What We Can Do About It.

If the word “traffication” comes readily to mind, then you are likely familiar with the work of British scientist Paul Donald. After decades spent studying the decline of many animal species, he realized he – and we – need a simple term summarizing the manifold ways that road traffic impacts natural systems. So he invented the word which serves as the title of his important new book Traffication: How Cars Destroy Nature and What We Can Do About It.

The field of study now known as road ecology got its start in 1925, when Lillian and Dayton Stoner decided to count and categorize the road kill they observed on an auto trip in the US Midwest. The science of road ecology has grown dramatically, especially in the last 30 years. Many road ecologists today recognize that road kill is not the only, and likely not even the most damaging, effect of the steady increase in traffication.

Noise pollution, air and water pollution, and light pollution from cars have now been documented to cause widespread health problems for amphibians, fish, mammals and birds. These effects of traffication spread out far beyond the actual roadways, though the size of “road effect zones” vary widely depending on the species being studied.

Donald is based in the United Kingdom, but he notes there are relatively few studies in road ecology in the UK; far more studies have been done in the US, Canada, and Western Europe. In summarizing this research Donald makes it clear that insights gained from road ecology should get much more attention from conservation biologists, transport planners, and those writing and responding to environmental impact assessments.

While in no way minimizing the impacts of other threats to biodiversity – agricultural intensification and climate change, to name two – the evidence for traffication as a major threat is just as extensive, Donald writes. He cites an apt metaphor coined by author Bryan Appleyard: the car is “the Anthropocene’s battering ram”.

Traffication has important implications for every country under the spell of the automobile – and particular relevance to a controversy in my own region of Ontario, Canada.

A slow but relentless increase

One reason traffication has been understudied, Donald speculates, is that it has crept up on us.

“These increases have been so gradual, a rise in traffic volume of 1 or 2 per cent each year, that most of us have barely noticed them, but the cumulative effect across a human lifetime has been profound.” … (All quotes in this article from the digital version of Traffication.)

“Since the launch of the first Space Shuttle and the introduction of the mobile phone in the early 1980s,” Donald adds, “the volume of traffic on our roads has more than doubled.”

Though on a national or global scale the increase in traffic has been gradual, in some localities traffication, with all its ill effects, can suddenly accelerate.

That will be the case if the government of Ontario follows through with its plan to rapidly urbanize a rural area on the eastern flank of the new Rouge National Urban Park (RNUP), which in turn is on the eastern flank of Toronto.

The area now slated for housing tracts was, until last November, protected by Greenbelt legislation as farmland, wetland and woodland. That suddenly changed when Premier Doug Ford announced the land is to be the site of 30,000 new houses in new car-dependent suburbs.1 And barring a miracle, the new housing tracts will be car-dependent since the land is distant from employment areas and services, distant from major public transit, and because the Provincial government places far more priority on building new highways than building new transit.

Though the government has made vague promises to protect woodlands and wetlands dotted between the housing tracts, these tiny “nature preserves” would be hemmed in on all sides by new, or newly busy, roads.

As I read through Donald’s catalog of the harms caused by traffication, I thought of the ecological damage that will be caused if traffic suddenly increases exponentially in this area that is home to dozens of threatened species. The same effects are already happening in countless heavily trafficated locales around the world.

“A shattered soundscape”

Donald summarizes the wide array of health problems documented in people who live with constant traffic noise. The effects on animals are no less wide-ranging:

“A huge amount of research, from both the field and the laboratory, has shown that animals exposed to vehicle noise suffer higher stress levels and weakened immune systems, leading to disrupted sleep patterns and a drop in cognitive performance.”

Among birds, he write,

“even low levels of traffic noise results in a drop in the number of eggs laid and the health of the chicks that hatch.” As a result, “Birds raised in the presence of traffic noise are prematurely aged, and their future lifespans already curtailed, before they have even left the nest.”

Disruptions in the natural soundscape are particularly stress-inducing to prey species (and most species, even predators, are at risk of being someone else’s prey), since they have difficulty hearing the alarm signals sent out by members of their own and other species. To compensate, Donald writes,

“animals living near roads become more vigilant, spending more of their time looking around for danger and consequently having less time to feed.”

A few species are tolerant of high noise levels, and seldom become road kill; their numbers tend to go up as a result of traffication. Many more species are bothered by the noise, even at a distance of several hundred meters from a busy road. That means their good habitat continues to shrink and and their numbers continue to drop. Donald writes that half of the area of the United Kingdom, and three-quarters of the area of England, is within 500 meters of a road, and therefore within the zone where noise pollution drives away or sickens many species.

Six-hundred thousand islands

When coming up to a roadway, Donald explains, some animals pay no attention at all, others pause and then dash across, while others seldom or never cross the road. As the road gets wider, or as the traffic gets faster and louder, more and more species become road avoiders.

While the road avoiders do not end up as roadkill, the road’s effect on the long-term prospects of their species is still negative.

When animals – be they insects, amphibians, mammals or birds – refuse to cross the roads that surround their territories, they are effectively marooned on islands. Taking account of major roads only, the land area of the globe is now divided into 600,000 such islands, Donald writes.

Populations confined to small islands gradually become less genetically diverse, which makes them less resilient to diseases, stresses and catastrophes. Local floods, fires, droughts, or heat waves might wipe out a species within such an island – and the population is not likely to be replenished from another island if the barriers (roadways) are too wide or too busy.

The onset of climate change adds another dimension to the harm:

“For a species to keep up as its climate bubble moves across the landscape , it needs to be able to spread into new areas as they become favourable . … In an era of rapid climate change, wildlife needs landscapes to be permeable, allowing each species to adapt to changing conditions in the optimal way. For many species, and particularly for road-avoiders, our dense network of tarmac [paved road] blockades will prove to be a significant problem.”

Escaping traffication

Is traffication a one-way road, destined to get steadily worse each year?

There are solutions, Donald writes, though they require significant changes from society. He makes clear that electrification of the auto fleet is not one of those solutions. It’s obvious that electric cars will not reduce the numbers of animals sacrificed as road kill. Less obvious, perhaps, is that electric cars will make little difference to the noise pollution, light pollution, and local air pollution resulting from traffication.

At speeds over about 20 mph (32 km/hr) most car noise comes from the sound of tires on pavement, so electric cars remain noisy at speed.

And due to concerted efforts to reduce the tailpipe emissions from gas-powered cars, most particulate emissions from cars are now due to tire wear and brake pad wear. Since electric cars are generally heavier, their non-tailpipe emissions tend to be worse than those from gas-powered cars.

One remedy that has been implemented with great success is the provision of wildlife bridges or tunnels across major roadways. In combination with fencing, such crossings have been found to reduce road kill by more than 80 per cent. The crossings are expensive, however, and do nothing to remedy the effects of noise, particulate pollution, and light pollution.

A partial but significant remedy can be achieved wherever there is a concerted program of auto speed reductions:

“Pretty much all the damage caused by road traffic – to the environment, to wildlife and to our health – increases exponentially with vehicle speed. The key word here is exponentially – a drop in speed of a mere 10 mph might halve some of the problems of traffication, such as road noise and particulate pollution.”

Beyond those remedies, though, the key is social reorganization that results in fewer people routinely driving cars, and then for shorter distances. Such changes will take time – but at least in some areas of global society, such changes are beginning.

Donald finds cause for cautious optimism, he says, in that

“society is already drifting slowly towards de-traffication, blown by strengthening winds of concern over human health and climate change.”

There’s scant evidence of this trend in my part of Ontario right now,2 but Donald believes

“We might at least be approaching the high water mark of motoring, what some writers refer to as ‘ peak car ’”. Let’s hope he’s right.

1 A scathing report by the Province’s Auditor General found that the zoning change will result in a multi-billion dollar boost to the balance sheets of large land speculators, who also happen to be friends of and donors to the Premier.

2 However, there has been a huge groundswell of protest against Premier Doug Ford’s plan to open up Greenbelt lands for car-dependent suburban sprawl, and it remains unclear if the plan will actually become reality. See Stop Sprawl Durham for more information.