One of the more puzzling features of modern life is the starkly contrasting visions of humanity’s near-term future. Watch thirty minutes of commercial-filled TV and you get a cheery sense that all is well in the world. A BMW, an anti-depressant, or a Caribbean vacation—these will ensure ever greater happiness.

At the same time, a 2021 poll in ten countries found that four in ten young people are hesitant to have children because of the climate crisis. And a 2022 American Psychological Association survey revealed that 76 percent of adults believed that “the future of our nation is a significant source of stress in their lives.“

Many documents crossing my desk embody these battling worldviews. I describe two below, whose distinct perspectives suggest that the question before us is, “Which future will we choose?” But a third report’s neutral evaluation of the future arguably hints at a more troubling question: “Which future have we likely already chosen?”

Space Vacations? No Vacations?

The first document was a report from McKinsey & Company, that collection of uber-smart analysts who monitor societal trends in search of opportunity and risk. A recent edition of their The Next Normal series, entitled “Could this be a glimpse into life in the 2030s?” featured a survey of a broad range of executives regarding likely developments in the next decade.

The executives’ visions are candy for the imagination. They include vacations in space, and even on Mars; flying taxis; smart packaging (eat your potato chip bag!); packages delivered by drones; immersive and interactive movies; and hotel rooms customized to a guest’s tastes, among others. McKinsey is bullish on the possibilities: “…chances are, in 2035 or thereabouts, much of what’s described…will indeed just be…normal.” So, there’s that. Let’s call McKinsey’s vision Exhibit One.

Exhibit Two is a document from the Post Carbon Institute called “Welcome to the Great Unraveling: Navigating the Polycrisis of Environmental and Social Breakdown.” You might guess that Institute staff is singing a different tune about the human future, and you’d be right. The report reviews the modern “polycrisis,” that mix of causally overlapping global crises that seem to be building to a climax. We’re all likely familiar with the litany of woes: species loss, climate change, deforestation, soil erosion, water scarcity, and collapsing fisheries, to name a few. It also includes social and economic crises from inequality to violence.

Pick a resort. (NASA)

The worsening of these crises and their impacts on society is the Great Unraveling. This unraveling, in turn, emerges from the Great Acceleration, the turbocharged economic activity of the past century characterized by remarkably high levels of materials and energy intensity. The widespread availability of cheap energy, especially fossil fuels, drives the Great Acceleration.

The report speaks plainly: “This unraveling will present a far greater challenge than the recent global pandemic. It will affect everyone, it will persist and worsen, and, if we do nothing, it may not be humanly survivable.” The report asserts that reducing humanity’s planetary footprint is incompatible with a growing global economy. It says that our planet can sustainably support just a few billion people at an equitable level of consumption. And it notes that shortages of critical nonrenewable resources could constrain the energy transition, among other conclusions.

The report’s bottom line is bracing. “The time available to prevent unraveling has elapsed. We have only a brief period in which to find ways to hold together the most vital of threads, while contending with the cascading consequences of misguided human actions to date.” What a contrast to the “all we need is political will” earnestness that concluded so many sustainability reports over the past half century! Notably, the report does not mention vacations of any kind, and certainly not trips to Mars.

Indeed, in reviewing the two reports, I had to wonder if the Post Carbon Institute is on McKinsey’s email list, and vice versa. And if the two organizations are headquartered on the same planet. I did not, however, wonder which of the two perspectives seemed closer to the mark.

A Guide for the Perplexed

Anyone who is unclear about which of these perspectives is more credible could find help in Exhibit Three, a 2021 paper from the Journal of Industrial Ecology entitled “Update to Limits to Growth.” It revisits the 1972 Limits to Growth study and its 2004 update, applying contemporary empirical data to them for a fresh evaluation of the Limits to Growth approach.

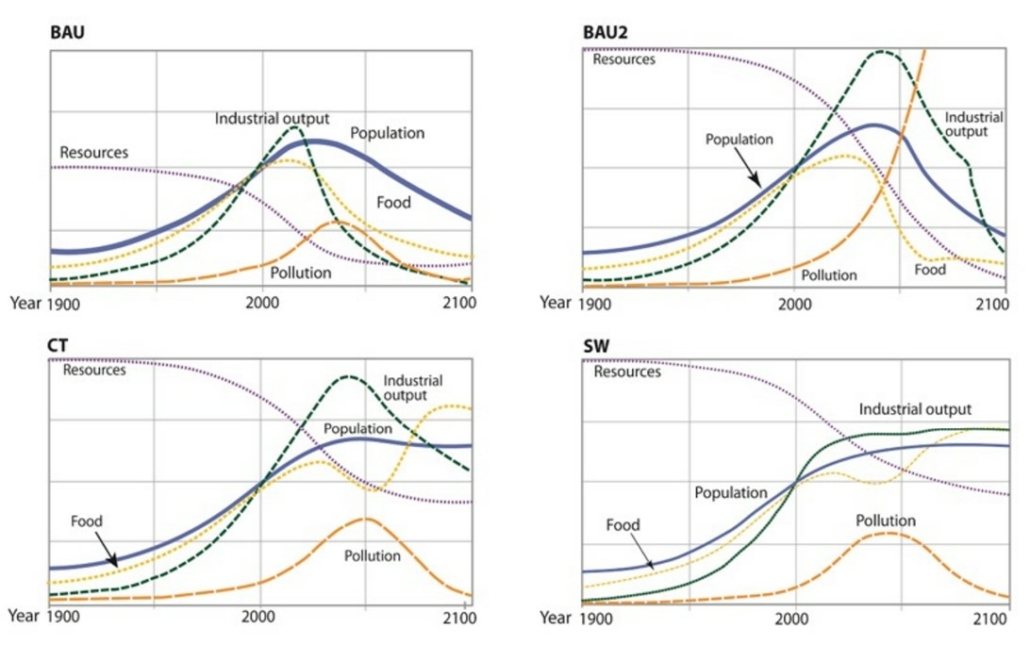

The Limits to Growth studies are based on computer modeling that produces various scenarios of the future. These include the possibility of a major contraction of the economy, and the social and demographic dislocation this implies, a scenario it calls collapse. The 2021 update, undertaken by Gaya Herrington, author of Five Insights for Avoiding Global Collapse explores how variables like population, food production, materials use, pollution, and others interact to produce alternative societal outcomes.

Like the 1972 study, Herrington’s study does not predict the future, so her work cannot be used to determine whether the perspective of McKinsey or the Post Carbon Institute is closer to the truth. Instead, her study equips readers to make that determination, by revealing the assumptions that go into creating each scenario. Assess which of the assumption sets is most credible today, and which is the set we’d prefer to see, and you can evaluate each scenario.

The four scenarios and their assumptions are these:

- Business as Usual (BAU) assumes that materials and energy use, population growth, and the policies that govern them continue their current courses. This scenario captures the worldview of people who don’t follow trends in the economy, energy, pollution and other society shapers. It represents those who cannot or will not recognize today’s gathering ecological and social storm clouds.

- Business as Usual 2 (BAU2) is similar to BAU, but assumes twice the level of resource availability. People comfortable with BAU2 arguably include those who delight in noting that the posted reserves of many resources continue to increase despite steadily increasing consumption. (Just don’t ask them why many resources are increasingly difficult to access and extract.)

- Comprehensive Technology (CT) foresees extraordinarily high levels of technological investment in future economic development. The McKinsey perspective might fit here. Governments can manage resource or pollution constraints using advanced technology and innovation.

- Stabilized World (SW) assumes a sharp shift away from industrial growth and toward investments in health, education, and ecological protection. The Post Carbon Institute would likely favor this one.

Which of these scenarios’ starting points (assumptions) sounds most like today’s world? That we can continue the present course? That resource availability is actually twice the current levels? That technology will save the day? Or that we will abandon the industrial growth model and invest in people and the planet?

And which scenario would you prefer to guide human development over the coming decades?

Having identified your preferred starting assumptions, look at the outcome of each scenario after the model is run.

| Scenario | Assumptions | Outcome |

| Business as Usual (BAU) | Policies and practices can continue their current paths | Collapse, due to depletion of natural resources |

| Business as Usual 2 (BAU2) | Resource availability is double current levels, with no changes to policies and practices | Collapse, due to pollution |

| Comprehensive Technology (CT) | Heavy investments are made in technology and innovation | Steep decline in economy because rising costs for technology eventually cause economic decline, but not a complete collapse. |

| Stabilized World (SW) | The industrial growth model is abandoned in favor of investments in people and the planet | No collapse as the economy and population stabilize, with human welfare preserved at a high level |

Source: Herrington, 2021.

Personally, I’m partial to the “no collapse” outcome associated with the Stabilized World scenario. Little wonder: This is the scenario that looks most like the steady state economy. It’s also the one closest to the Post Carbon Institute vision. On the other hand, I admit that Stabilized World is least likely to prioritize flying taxis and immersive movies.

The figures below depict the outcome of each model. The spaghetti-like trend lines are easiest to decipher by zeroing in on the sharp peaks and subsequent crashes. In the first three graphs, industrial output (the economy) reaches a maximum, then falls sharply—the collapse dynamic. But in the Stabilized World chart (bottom right), the only curve with a peak and crash is pollution! Industrial output and population are both steady—the essential dynamics of a steady state economy.

The timing of the crashes is also interesting. The graphed trends are not predictions, but it’s hard not to notice that industrial output in the first three scenarios peaks before mid-century, i.e., within the next decade or two. Even if the timing is off, the critical dynamic revealed in several scenarios—that of peaks and crashes—should grab us by the shoulders and shake us, no matter when we think it might arrive.

Peaks often spell trouble. (Herrington)

The Comprehensive Technology graph deserves a bit of elaboration given that it did not result in outright collapse and given humanity’s propensity to place faith in technological fixes. First, note that industrial output in the CT graph, while not falling to the extent found in the BAU and BAU2 graphs, does in fact fall, a marked shift from the ever upward trendline of the twentieth century. This represents a major economic dislocation, even if it is not full collapse.

More important, Herrington raises a philosophical objection to the Comprehensive Technology scenario. Even if CT performs better than the BAU scenarios, is it the human vocation to be technocrats, or to be humans embedded in nature? Here is how she puts it:

Why would we use our innovative powers to invent robot pollinators to replace the bees, if we also have the choice to invent agricultural practices that do not have the side effect of insecticide? Why use drones to plant new trees, when we could also restructure our economic priorities so that existing rainforest is not cut and burned down? Now that humanity has attained truly global reach, now that we have an unprecedented power to shape our own destiny, limits to growth force upon us the question: Who do we want to be and what world do we want to live in?

Yes: Who are we and what future do we want? These are essential framing questions.

What Shall We Do?

Back to the future? (PxFuel)

The Great Unraveling report expresses skepticism that government and business will act quickly and robustly enough to avert crisis. (Nevertheless, in my view, citizens should continue to organize on this front). Formidable obstacles stand in the way of effective policymaking, from our focus on the short term and bias toward sunk costs to the growth imperative of capitalism.

Instead, the report focuses on what individuals and communities can do—basically, build resilience at all levels. Psychologically, people and communities need to steel ourselves for the challenging times ahead. Socially, we need robust community ties for effective mutual assistance in periods of stress. And at a practical level, we’ll need to build skills, from gardening and canning to carpentry, plumbing, and electricity, as a means of developing capacity for maintaining and caring for infrastructure.

Lest we lose all hope, we would do well to take to heart one of Herrington’s insights for avoiding collapse. She writes that the end of growth does not spell the end of progress but could mean quite the opposite. Of course, if we insist on comparing a no-growth future to the growth model that promises customizable hotels and adventures in space, we will be disappointed, all the way to the ultimate disappointment of a collapsed economy and society.

But if we focus on assets like strong relationships, health, education, and other measures of wellbeing, we may surprise ourselves. A civilization with a decent quality of life based on renewable energy and renewable and reused materials, and guided by a strong ecological and humanitarian ethic, could offer a path forward that is worthy of the label “human.” Maybe McKinsey & Company, reorganized as a worker’s co-op and managed by the Post Carbon Institute, can get started on this?