Something new and troubling is happening as economies grow across much of the globe. In contrast to prior decades, when human health improved as global GDP swelled, the link to health progress has been broken. No longer is economic growth delivering a health dividend, it seems.

Meanwhile, another metric, the health of the environment, has continued to deteriorate with economic growth. We now face a “ghastly” global environmental crisis, in the words of an esteemed lineup of scientists.

The new reality raises an urgent question: Are the benefits of economic growth starting to run their course, even as the downside of growth gallops ahead?

Health No Longer Improving with GDP

Average levels of human health have undoubtedly risen and fallen many times over the past two million years as social and ecological conditions have changed. Around ten millennia ago, the shift from gathering and hunting to the practice of agriculture caused health to take a turn for the worse. But in the 20th century public health measures reduced the toll taken by infectious disease, and life expectancy increased dramatically. Health progress continued into the 21st century and until recently had a statistical association, albeit a weak one, with economic growth.

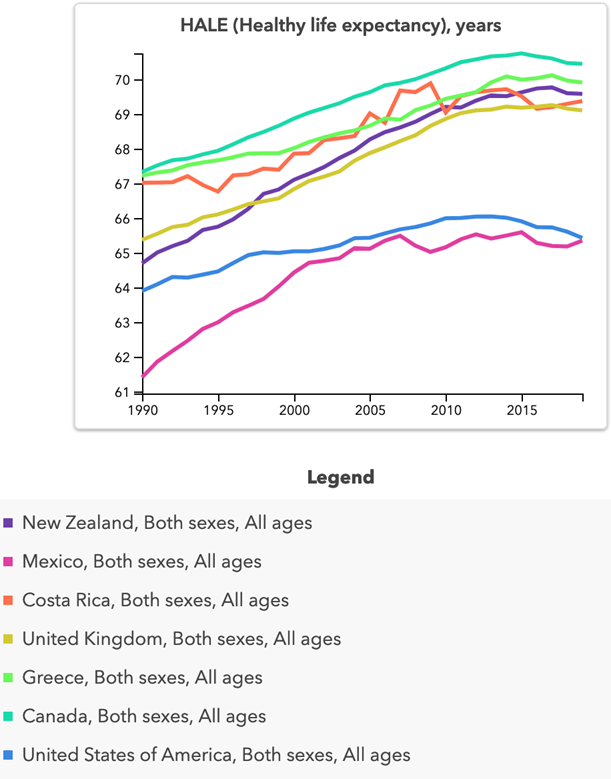

Then, halfway through the last decade—five years before the onset of COVID-19—health stopped generally improving with the rise in GDP. For example, in the USA average life expectancy started to fall while GDP per capita continued to rise. A more comprehensive metric, called Healthy life expectancy takes into account not only the average length of life, but also the average duration and severity of disease over the course of life.

Richer and sicker since 2014: Selected countries (IHME)

On the flip side of the disconnect between health and growth, healthy life expectancy has risen since 2014 in a number of countries with falling GDP per capita, like Argentina, Lebanon, and Namibia. To track the relationship—or lack thereof—between GDP and health, I analyzed the most comprehensive statistics published by the Global Burden of Disease Collaborative Network (GBDCN). The GBDCN is the world authority on healthy life expectancy and provides data for the years 1990-2019.

Across 102 countries and the 25-year period 1990-2014, healthy life expectancy rose by an average of one-sixteenth of one percent for each percent of growth in GDP per capita. This is quite a weak (but statistically significant) relationship. Such a link is detectable over shorter time scales as well, including the five years 2010-2014.

But after 2014, the relationship between economic growth and health progress vanishes. For the period 2015-2019, there is no statistically significant relationship, positive or negative, between GDP per capita and healthy life expectancy. The same goes for the average degree to which people suffer from disease while still alive. (The statistic used to track this suffering—”years lost to disability”—has increased more than can be explained by increasing average age alone.) The reasons health no longer improves with growth likely differ between countries. But it stands to reason that the environmental damage wrought by economic growth has something to do with it. Let us turn now to this topic.

Environment Still Degrading with GDP

Across the same 102 countries and 30-year time period, environmental impacts have continued to mount with GDP. From 1990 through 2014, use of raw materials (actually overuse, given its contribution to ongoing breaches of planetary boundaries) increased by an average of nearly two-thirds of a percent for each percent of growth in GDP. From 2015 through 2019, the relationship between GDP and material throughput not only persisted but worsened, with material footprints expanding by more than one percent for each percent of growth in GDP.

Overuse of land and water—the number one driver of mass extinction—also continued to worsen with GDP growth, again from 1990 through 2019. These metrics of material and land use are implicated in a huge number of other environmental problems, such as climate chaos, toxic waste, and algae blooms.

In sum, we are witnessing the dissolution of the association between economic growth and health progress, not only in selected countries like the USA, but among countries in general. And we see that ecological damage remains firmly coupled to economic growth, even in the most recent short-term (five-year) period for which data are available. This is the same period in which human health decoupled from economic growth.

Get Smarter, Not Richer

Given that economic growth is no longer conducive to health improvement, are there more ecologically benign routes to human flourishing? Policy recommendations by degrowth advocates point to many such routes. In this final section, let’s consider one of the most basic: enhancing access to education.

University of Vienna researchers recently found that health progress is linked much more tightly to educational attainment than to GDP. The 102-country dataset used for the decoupling assessment above confirms this result. During the post-2014 period in which health improvement decoupled from economic growth, healthy life expectancy increased with average years of schooling, and levels of suffering from disease decreased with average schooling.

Moreover, unlike GDP, which still had strong links to material and ecological footprints during this period, educational attainment had no relationship, positive or negative, to these metrics of environmental impact.

In sum, the empirical analysis reported above vindicates the ecological stance against economic growth and refutes the mainstream insistence on growth. To promote both human health and environmental quality, countries would focus not on growing the GDP, but rather on different goals including education.