The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms

Directed by Eugène Lourié; written by Fred Freiberger and Lou Morheim from a short story by Ray Bradbury; cinematographed by Jack Russell; animation effects by Ray Harryhausen; edited by Bernard W. Burton; music by David Buttolph; production design by Lourié; produced by Jack Dietz. Cast includes Paul Christian, Paula Raymond, Cecil Kellaway and Kenneth Tobey. Released in June 1953 by Warner Bros. Pictures. Running time: 80 minutes. Black and white.

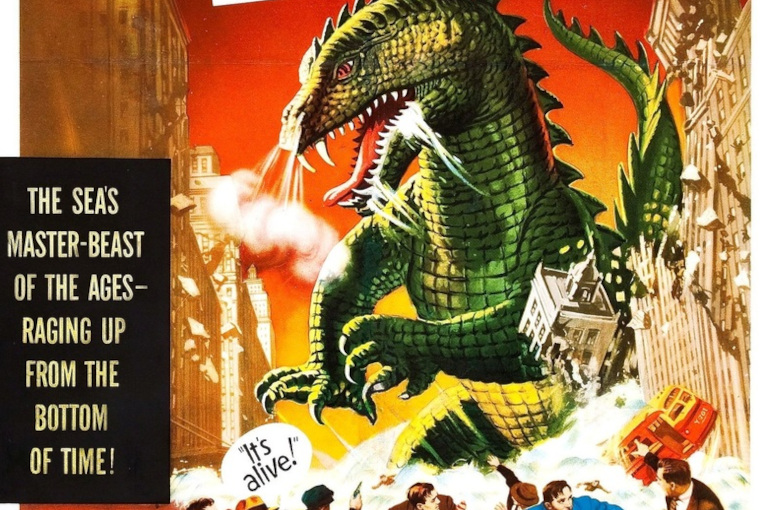

This year marks 70 years since the initial release of the B-movie cult classic The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms. This was one of the first monster movies of the 1950s, and the very first to feature a giant prehistoric creature awakened by nuclear tests and unleashed on the modern world. It established the template for a host of other creature features and directly inspired Godzilla, which came out the following year.

Godzilla and this film can both be seen as modern-day parables warning of the consequences of unchecked scientific hubris and heedless meddling with nature. By portraying their monsters as nearly invincible, they’re implying that to toy with the destructive power of atomic energy is to unloose forces beyond our ability to contain or control. The films counsel wisdom and restraint in our approach to scientific progress and the harnessing of power, lest we face the monstrous repercussions of real-life nuclear incidents.

Beast opens newsreel-style at a secret base in the Arctic Circle where military personnel and scientists are making last-minute preparations for an atomic bomb drop. Against David Buttolph’s eerie, ominous music, the narrator solemnly warns us about the danger of the impending test. After a dramatic countdown, the bomb blows with a sudden flash (plainly just someone switching a light on and off), an elemental rumble and that iconic mushroom cloud.

As the cloud ascends and the roar reverberates, we cut to shots of an ice shelf crumbling into the ocean. Then, in a moment that has since become a monster movie cliché, someone notices something strange on a radar screen and a team heads out with Geiger counters to investigate. It’s here that we first see the beast.

Bucking the usual monster movie trope of delaying the creature’s full reveal until at least the halfway mark, this film shows its monster within the first 10 minutes. The early shots of it look great, a testament to the enduring power of old filmmaking techniques like stop-motion photography. Legendary model animator Ray Harryhausen was in charge of the effects used to bring this creature to life, and he managed to give it a palpable presence that today’s computer-generated monsters often fail to match. Indeed, in the words of the late great film critic Roger Ebert, “Stop-motion looks fake, but feels real. CGI looks real, but feels fake.”

The monster’s realism is enhanced by the fact that it’s first shown in the midst of a heavy storm, with the low light and driving snow acting to conceal potential flaws in the model. Also, we don’t see it directly interact with the human characters at first, so there’s none of the cringey fakeness that often plagues older movies that try to integrate stop-motion models with live-action humans. (That comes later, once the monster reaches the city and begins terrorizing its inhabitants.)

We come to learn that the creature is a dinosaur, a member of the fictitious species Rhedosaurus. Its anatomy is a chaotic jumble: From the neck up, it looks like the meat-eating Allosaurus, while from the shoulders down it has the distinctive downward-sloping back and elongated front legs of the great plant-eater Brachiosaurus. A line of huge spikes runs down the length of its neck, back and tail. As we get a sense of its true size, we realize it’s far larger than any known real-life dinosaur ever was, but not nearly as large as Godzilla.

Physicist Thomas Nesbitt (Paul Christian) is the sole survivor of the initial brush with the dinosaur, and he tries to warn others of its existence. Of course, no one believes him; and meanwhile the creature begins traveling southward through the ocean, leaving destruction in its wake as it makes its way down the east coast of North America.

The plot contains numerous elements that have gone on to become monster movie clichés, including the earnest young scientist whose warnings go unheeded (Christian), the older scientist who obstinately rejects the evidence (Cecil Kellaway), the romantic subplot between the earnest young scientist and the clear-eyed woman who believes and advocates for him, the monster’s destructive rampage through populated areas, the military’s failed attempt to combat it with conventional means and the eventual discovery of a vulnerability through which to defeat it.

Another monster movie cliché present in Beast is the half-hearted attempt to provide some semblance of scientific justification for the creature’s existence. In a risible attempt to rationalize to the older, skeptical scientist how a dinosaur could potentially enter a state of suspended animation, Nesbitt cites the example of a bear hibernating during winter. But the older man quite sensibly counters that the notion of a 100-million-year hibernation is absurd (though he later changes his mind on this, with an abruptness that shatters credulity).

As with many ’50s monster movies, the acting performances in Beast are a mix of seriousness and camp. Christian, for example, lends an element of gravitas to the story with his straight-played performance, while Kellaway adds levity with his delightful portrayal of a fusty academic more concerned about his long-overdue upcoming vacation—his first in 30 years!—than the impending threat others are trying to warn him about.

For those who love a good creature feature, there’s much to enjoy in what follows. There’s suspense and tension as the monster continues its relentless march and escalates its attacks. There are those now-iconic command center scenes in which our hero works with various military people and scientists to devise a plan to stop the beast. There’s thrilling mayhem and wanton destruction in the streets of New York. There are high-stakes battles and chases all culminating in a spectacular final showdown on Coney Island.

At 80 minutes, this movie is the perfect length. It comes from a time long before our current era of absurdly long runtimes, a time when the term “feature film” meant an hour and a half of concise, captivating storytelling.

The credits for Beast say that it was “suggested by” a story by Ray Bradbury. I’m afraid even that’s a bit of a stretch, for almost nothing about the original story found its way into the movie. The film’s only recognizable trace of its supposed source material is a scene in which the dinosaur comes ashore and attacks and topples a lighthouse. In the story, this scene is a source of pathos. We’re watching a lonely animal drawn ashore by what it thinks is the call of another of its kind—but is really the lighthouse foghorn—only to be devastated by the discovery that its perceived connection was merely an illusion. But the movie strips this scene of its original context and turns it into a mere action spectacle. Bradbury’s original poetry was discarded in favor of entertaining schlock.

Despite how different the world of today is from that of the ’50s, the environmental and ethical concerns embodied by ’50s movie monsters remain as relevant as ever—and we continue to grapple with them in the form of both new movie monsters and endless revivals of familiar ones like Godzilla.