This article first appeared on ARC2020.eu. ARC2020 is a platform for agri-food and rural actors working towards better food, farming, and rural policies for Europe.

EU Agriculture is in crisis mode. And so is the CAP. For two years in a row, the CAP crisis reserve has been spent to help farmers deal with the adverse consequences of the invasion of Ukraine and climate change. At the same time, Member States are asking for reduced environmental obligations in 2024. What happened during this week’s AgriFish council CAP wise? We guide you through the updates.

Introduction

Since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, and particularly since the invasion of Ukraine, the agricultural sector has found itself embroiled in an ongoing crisis. Adding to these challenges, the European Union is now confronted with the far-reaching effects of climate change, with droughts, wildfires, and floods becoming increasingly prevalent.

Farmers are facing significant hardships, and in an effort to address this, funding from the EU and Member States has been distributed without regard to social or environmental standards. Additionally, derogations on environmental requirements in the CAP have been allowed in 2022 and 2023.

The way we respond to crisis within the CAP is a cause for concern. One might question whether the CAP is gradually losing its “common” character.

The growing flexibility in the distribution of funds lacks adequate accountability. These circumstances prompt several important questions. To what extent has deregulated aid been distributed? What are Member States proposing for the months and years to come? Additionally, how can we effectively manage crisis in the future?

Rural landscape in Germany

Crisis reserve, the tree that hides the forest

In French, we use the expression “the tree that hides the forest” to refer to a detail that captures all our attention while concealing the whole of something else. Although the use of millions of euros through the crisis reserve is not a detail, it certainly is not the whole story.

In a recent statement at the EU parliament in Strasbourg, AGRI commissioner Wojciechowski confirmed that “we are increasingly turning to national public aid”. In response to the invasion of Ukraine only, Member States have provided more than €7 billion in aid to farmers.

In March 2022, the CAP crisis reserve, which has an annual budget of €450 million, was activated for the first time since its establishment in 2013. The crisis framework provided €500 million to Member States with a top up option of national aid of 2 to 1 (€1 billion). In addition, ceilings for national aid programs had also been raised.

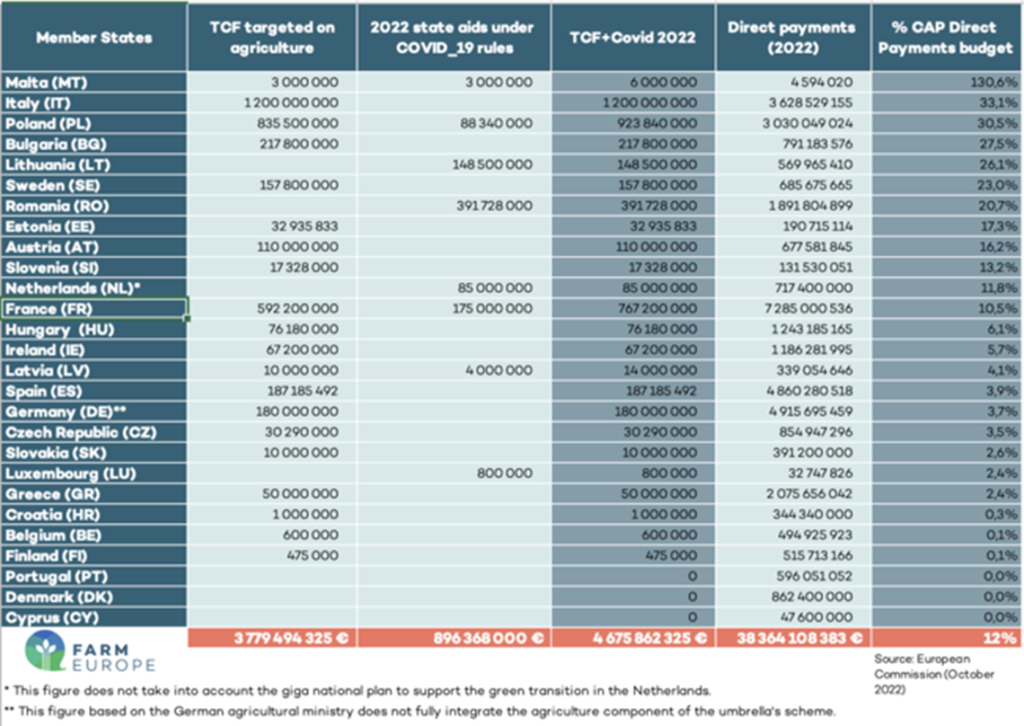

Consequently, almost 4 billion euros were disbursed through various aid programs – no strings attached. Additionally, agricultural entities have received state aid through residual programs associated with the Covid-19 pandemic. In the year 2022 alone, this amount represents approximately 12% of the annual budget allocated for direct payments.

Figure 1: assessment of aid programs by country (sources: Farm-Europe)

According to Farm-Europe, these numbers only give a partial view of the real aid granted by the Member States.

For instance, in light of the repercussions caused by the invasion of Ukraine, over €450 billion in state aid has been allocated through framework programs to bolster the overall economy of the European Union, with the agricultural sector being among the beneficiaries.

Another concern lies in the varying approaches adopted by Member States when implementing aid programs. While certain countries have injected significant amounts of money that surpass inflation rates, offering support beyond mere compensation, others have been not been able to provide support for political or budgetary reasons. This also raises the question of fairness in an open market where all farmers are competing.

State of the 2023 crisis reserve: almost empty

This week, Member States have approved the €100 million support package for farmers in Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, Romania and Slovakia, to ease the blow of Ukraine grain influx.

Additionally, the Commission is proposing a new support package of €330 million for 22 Member States “impacted by adverse climatic events, high input costs, and diverse market and trade-related issues”.

Two years in a row, the full crisis reserve budget of €450 million per year was spent before summer.

The various responses to crises and additional financial injections raise concerns regarding the adequacy of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) budget. According to Wojciechowski “with a CAP budget of 0.4 % of GDP, we will not be able to respond effectively to the big challenges faced by agriculture”. He also specifically addressed the fact that the crisis reserve was insufficient.

But are we going to make our agricultural systems more resilient by just inflating the general budget of the crisis reserve? It is doubtful. Even if the raging war in Ukraine ends and no more pandemics hit us directly, droughts and floods will only increase with time. And the budget will not be able to follow this trend.

Farmers are the first impacted by these crises and it is only fair to provide them with assistance. But at some point, we need more liability when distributing money.

Greenhouses in Almeria, Spain

Less accountability: 2024 CAP derogations

It is not only about money, it is also about how we spend it. And right now, aid programs are not linked to social or environmental requirements. Worse, while the crisis reserve is emptying, Member States are still pushing for more environmental derogations in the CAP.

Since 2022, Member States have been granted the ability to deviate from the requirements of greening measures and Good Agricultural and Environmental Conditions (GAEC) standards in the name of food security. However, the initial available data has demonstrated the inefficiency of these derogations in effectively increasing food supply.

Nevertheless, during this week’s AgriFish council, certain Member States (LV with the support of CZ, EE, FI, HU, LT, PL, RO) have put forward a proposal to grant derogations within the CAP for the year 2024. The main reason for this request? At risk food security because of extreme weather conditions, especially droughts.

And this time, the request goes even further than before. The proposal aims to potentially permit derogations not only on GAEC standards but also on eco-schemes and agri-environmental measures from pillar 2. The idea is to simplify the amendment procedure to allow flexibilities in amending the different CSPs to allow for those derogations.

The objective would be to “allow non-productive agricultural land such as buffer strips, field margins and fallow land to be used for food and feed production”. The Latvian minister continued by stating that “this would be a specific measure for this extraordinary specific circumstance… to maintain (agricultural) resilience this year”.

All the other Member States that took the floor (FI, CZ, EE, FI, HU, LT, PL, RO, CY, IT, BG, MT, SK, EL, DK, FR, ES, PT) supported this proposal. Only Germany was more tempered, asking for an evaluation of appropriate measures.

Commissioner Wojciechowski reacted first by reminded all the measures from the new support package:

- Use of the crisis reserve

- Allow payment of advances under both pillars

- Flexibilities in sectorial programs

- Assessment of exceptional amendments

- Temporarily EU state aid rules: mobilisation of national resources to support farmers

He reminded that “while looking for short-term relief, we must provide long-term solutions”. On derogations, he mentioned that “their adverse impact on the environment will delay the transition towards resilient agriculture”. Nevertheless, he ensured that “the commission remains open to look at targeted amendments of the CAP where needed”.

In previous years, derogations were allowed unilaterally for all countries. This time, it seems that each Member State will need to go through amendment requests under a simplified and flexible procedure (for additional info on how to amend the CAP, check our previous article).

It is unclear if the Commission will be willing to take a stance and reject amendment proposals. But looking back at the recent history, it doesn’t seem like it would.

Chicken farm in Cywiec, Poland

Climate Change and Resilience 101

While listening to the various delegations expressing their opinions on CAP derogations, a fundamental question arises: Do our leaders truly comprehend the concept of climate change?

They are calling for extraordinary measures for extraordinary circumstances. But climate change means that those circumstances are not extraordinary anymore. Attempting to address the consequences of droughts on an annual basis will only exacerbate the situation further.

The Latvian minister talked about “ensuring resilience this year”. But resilience is not a concept to be assessed on a yearly basis. This completely undermines its meaning. Resilience is a systemic characterisation that defines resistance to shocks. If system modifications are needed to adapt to a shock, that means the system is not resilient yet.

Everyone knows this. If you give a fish to a hungry person, he will eat one day. If you teach him how to fish, he will eat all his life. This saying is a bit simplistic of course. Learning to fish takes some time and while the person in question is still hungry, fish should be provided.

With agriculture, it is pretty much the same story. If a farmer struggles with droughts, we should help him. But at the same time, we should ask for some accountability by transitioning the practices towards drought resistance. In that sense, distributing money while advocating for lower environmental restrictions is the opposite of what should be done.

This is a story that every child learns at some point. Yet, it seems to have been forgotten by the people with the most power.

Download this article as a PDF

This article is produced in cooperation with the

This article is produced in cooperation with the

Heinrich Böll Stiftung European Union.