Some books get a ‘reputation’ as a result of what people believe they say rather than on a detailed reading of the text. Just a word in the title – for example, ‘collapse’ – can be enough for commentators to invalidate their content without any appreciation of what they actually say.

Some books get a ‘reputation’ as a result of what people believe they say rather than on a detailed reading of the text. Just a word in the title – for example, ‘collapse’ – can be enough for commentators to invalidate their content without any appreciation of what they actually say.

Free download, via the Internet Archive.

This is the third in a mini-series of four: The first, ‘Farewell to Growth’, took an economic view of why consumer society cannot persist; the second, ‘Overshoot’, considered the sociological viewpoint on modernity’s imminent end; this review, of Joseph Tainter’s ‘The Collapse of Complex Societies’, considers the historical viewpoint on why societies fail to persist.

‘Collapse’ considers over a dozen ancient civilisations that, for a variety of reasons, collapsed and ceased to function. This is the part of the book which people focus upon, because – on a cursory reading – that is the argument being laid against modern society:

“Collapse is recurrent in human history; it is global in its occurrence… A complex society that has collapsed is suddenly smaller, simpler, less stratified, and less socially differentiated. Specialisation decreases and there is less centralised control. The flow of information drops, people trade and interact less, and there is overall lower coordination among individuals and groups… Population levels tend to drop, and for those who are left the known world shrinks.”

To say that the book is about ‘collapse’, I believe, is wrong.

The focus of the evidence, gleaned from archaeological excavations, is not that ‘societies collapse’; clearly, all eventually will. The message is far more nuanced, relating not simply to resources, or war, but the role that ‘complexity’ has in both driving society’s growth and its ultimate collapse:

“Complexity is generally understood to refer to such things as the size of a society, the number and distinctiveness of its parts, the variety of specialised social roles that it incorporates, the number of distinct social personalities present, and the variety of mechanisms for organising these into a coherent, functioning whole. Augmenting any of these dimensions increases the complexity of a society.”

Many dismiss the ‘collapse’ hypothesis, arguing that our greater scientific and technological capabilities prevent this from happening to society today. That belief demonstrates a fundamental misunderstanding of how complexity functions.

What makes a society vulnerable to collapse is the level of human effort required to keep it operating: As described by the Second Law of Thermodynamics, human societies create greater complexity by investing more resources in systemic diversity; but if that social complexity is to persist, then that stream of energy and resources must be maintained.

As Tainter says:

“More complex societies are more costly to maintain than simpler ones… As societies increase in complexity, more networks are created among individuals, more hierarchical controls are created to regulate these networks, more information is processed, there is more centralisation of information flow, there is increasing need to support specialists not directly involved in resource production, and the like… The result is that as a society evolves toward greater complexity, the support costs levied on each individual will also rise, so that the population as a whole must allocate increasing portions of its energy budget to maintaining organisational institutions.”

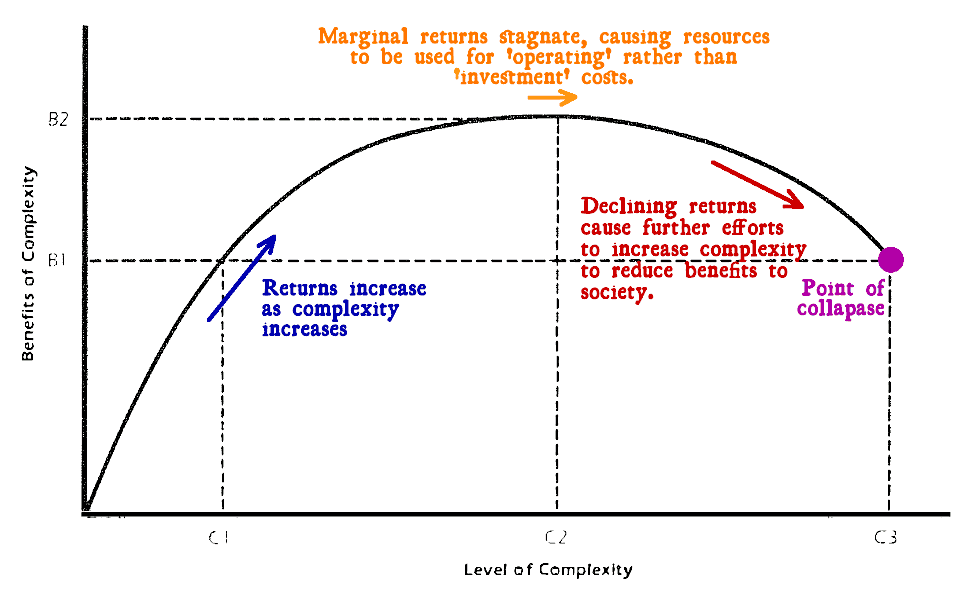

This is the point where Tainter brings-in ‘marginal cost’, and how that affects social structures. Better organisation, integration, and specialisation confers ‘marginal gains’ across society, driving development. However, there inevitably comes a point where those gains not only reduce to zero, but reverse, costing society more with its continued growth:

“It is suggested that the increased costs of sociopolitical evolution frequently reach a point of diminishing marginal returns. This is to say that the benefit/investment ratio of sociopolitical complexity follows the marginal product curve… After a certain point, increased investments in complexity fail to yield proportionately increasing returns. Marginal returns decline and marginal costs rise. Complexity as a strategy becomes increasingly costly, and yields decreasing marginal benefits.”

Figure 19. ‘The Collapse of Complex Societies’.

Therefore, the critical argument the book presents for us today is, ‘where on this curve of marginal costs and benefits are we now?’

Humans have ‘reaped’ the benefits of complexity since urbanisation began 9,000 years ago – coincidental to our development of metallurgy. Whether ‘technological society’ is at or beyond the peak of the trend is open to interpretation: The ‘diminishing returns’ of uncontrollable climate change, chemical pollution, and soil loss – which have increased dramatically over the last fifty years – objectively indicate we have passed the midpoint.

As resource depletion and the social costs of urbanisation and globalisation begin to bite, are we now seeing the terminal decline Tainter outlines?

“…a society experiencing declining marginal returns is investing ever more heavily in a strategy that is yielding proportionately less. Excess productive capacity will at some point be used up, and accumulated surpluses allocated to current operating needs. There is, then, little or no surplus with which to counter major adversities. Unexpected stress surges must be dealt with out of the current operating budget, often ineffectually, and always to the detriment of the system as a whole. Even if the stress is successfully met, the society is weakened in the process, and made even more vulnerable to the next crisis.”

Like Lewis Carroll’s ‘Red Queen’, technological society is running faster-and-faster to stand still, just at the point where the trends which support that complexity – such a scientific discovery or energy supply – are tailing-off. Clearly, from Tainter’s description of past societies, this doesn’t look good!

Reading the detail of Tainter’s case, the aspects of self-delusion and short-term decision-making which characterise human society operate outside of technology or scientific knowledge – since those ‘rational’ factors are themselves an emergent product of complexity. 35 years after its publication, what this book shows is that transcending ‘collapse’ requires not ‘more technology’, or ‘better science’, but a different model for how we provide for our needs; at the heart of which must be process of decreasing systemic complexity in order to increase our resilience to systemic shocks.

After-thoughts on ‘The Collapse of Complex Societies’

This is the third of four related reviews, the relevance of which, I’m almost certain, will escape the perceptions of quite a few – and annoy a few more who do accept the underlying theme of this series. Therefore, I think it’s worth being clear why I’m grouping these works together, which is something I’ll develop in the ‘afterthoughts’ section of each review.

This has been yet another really hard-to-write review: The case Tainter makes in over 200 pages can’t insightfully be reduced to less than a thousand words! I read this book about twenty years ago, and ever since I’ve been amazed by how often I see the kind of blinkered, or short-term thinking which plagued past human societies, manifest itself today. Unfortunately, communicating this reality involves challenging some of the greatest shibboleths in society today.

I chose this as the third in this miniseries because, like the other two, what this book points to is a reality many people unconsciously choose to avoid: That at the heart of modern society lies an all too human form of self-delusion, a product of our alleged ‘rational’ consciousness, which prevents us seeing certain trends where they conflict with our engrained social identity.

The social commentator, Upton Sinclair, famously said, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends upon his not understanding it!” That would be one interpretation of what Tainter describes in relation to the archaeological evidence for why societies collapse. In reality the patterns the book lays out are more… complex!

In recent months I’ve been reviewing a lot of social psychology and ‘post-post-modernist’ criticism. Philosophy and criticism are emergent properties of society, given form by all that additional complexity created by science and technology; and so are a means to examine the difficult-to-discuss trends our dominant culture exhibits:

- ‘Modernism’, and ‘structuralism’, began around the turn of the Twentieth Century as industrialisation ceased to maintain the older aristocratic empires of Europe, and instead spawned its own, technocratic forms of government to supplant those older forms of autocratic control – notably, democratic organisation, justified through ‘rational’ forms of thinking, to create a mass, more highly technological ‘material consciousness’;

- ‘Post-modernism’, and ‘post-structuralism’, arose in the 1950s as a criticism of the distortions of society that industrialism’s ‘rational organisation’ began to dictate – in particular, the rise of globalisation and neoliberal economic ideology, and how that was over-turning traditional economic and power relations across modern society, subverting the original promise of modernism;

- Most recently, ‘post-post-modernism’, or ‘meta-modernism’, is the latest iteration of this cycle, arising contemporaneously with the global crises of the post-2001 world – and is ever-more critical of the entire arc of ‘modernism’ as it fails to create the future it promised, while creating wholly new intractable problems for the world to solve.

The countervailing trends which post-modernism sought to expose – and which latterly deep ecological thinking has taken outside of the purely human cultural domain and transposed into a critique of our biological role within nature – are describing exactly the same phenomena which Tainter sees in the archaeological record: Of a pattern of development, formed by a dominant understanding of the human relationship with the world around us, the operation of which ultimately undermines the promise or meaning at the heart of that culture, as the damage it causes creates greater public alienation.

As Vermeulen and Akker say in their essay on meta-modernism:

“…both meta-modernism and the post-modern turn to pluralism, irony, and deconstruction in order to counter a modernist fanaticism. However, in metamodernism this pluralism and irony are utilized to counter the modern aspiration, while in post-modernism they are employed to cancel it out. That is to say, meta-modern irony is intrinsically bound to desire, whereas post-modern irony is inherently tied to apathy.”

‘Aspiration’, versus ‘fanaticism’, versus ‘apathy’ – can you think of three better terms to describe the debate on climate change, or the liberal versus conservative ‘culture war’? That’s probably why many find post- or meta-modernist thinkers really annoying: They tear-down the fables which people tell themselves to justify the things they unconsciously do every day, pointing out, ironically, that ‘the King has no clothes’.

The structure of ‘The Collapse of Complex Societies’ clearly has some meta-modernist aspects, using past patterns of human culture to implicitly deconstruct our modern culture. For example, think back to Tainter’s description, via the graph, of how ‘marginal benefits’ rise, level out, and then fall, with increasing complexity:

- Throughout the arc of ‘modernism’ the underlying ‘logos’ – the framework of meaning driving society – has been one of improving human progress by applying rational knowledge and technological development to society’s needs;

- However, as time has progressed, from climate change to PFAS in the rain, all this trend has done is to render our world more fragile, while pandering to the whims of human excess – for an ever-smaller group of states and individuals as global ecological and economic inequality increases;

- Consequently, we see how it is the dominant culture of modern society setting the priorities for development, not the specific science or technological developments which carry out those demands, which enhance human organisational complexity and lock us ever-further into a ‘progress trap’.

In the book, and especially in relation to Ancient Rome, Tainter outlines how rising structural inequality in ancient societies, and the squandering of resources by a more insulated elite, typify the ‘late stage’ of change preceding collapse. This was a viewpoint Tainter formed in the 1980s, well before the unprecedented levels of global inequality created by neoliberalism since the 1980s.

That period – the 1980s – is significant:

Coming out of the First Oil Crisis of the 1970s, repeated by the Iranian crisis in 1980 which precipitated another global recession, neoliberalism sought to reform the organisation of society to make it more ‘economically efficient’ – to maintain the ideological goal of economic growth. Put simply, the ideology of globalisation and financialisation doubled-down on the growth-centric model of human development by applying ever-greater rationalisation to the use of resources – including people – to generate greater returns.

Via it’s ‘shock doctrine’, it applied neoliberal ideology to society as a whole, creating a globalised economic process which sought to intensify economic activity. And just as Tainter observed in ancient societies, that greater centralisation, differentiation, and synchronisation of state and people across the planet, has magnified the demands for energy and resources proportionately.

Early in Chapter 3, Tainter outlines the mechanisms that initiate social collapse:

“There appear to be eleven major themes in the explanation of collapse. These are;

1. Depletion or cessation of a vital resource or resources on which the society depends.

2. The establishment of a new resource base.

3. The occurrence of some insurmountable catastrophe.

4. Insufficient response to circumstances.

5. Other complex societies.

6. Intruders.

7. Class conflict, societal contradictions, elite mismanagement or misbehaviour.

8. Social dysfunction.

9. Mystical factors.

10. Chance concatenation of events.

11. Economic factors.As simple as it is to present this classification, there are still ambiguities. There is much overlap in the categories listed, while some themes could be subdivided further.”

Two of the causal factors Tainter observes at length are ‘climatic change’ and ‘resource depletion’ – both of which are beginning to have an ever-greater effect on human society today. Likewise many of the others, related to the failure of political representation as social inequality increases, can be seen manifesting across urbanised populations around the world.

I want to highlight one driver Tainter highlights: ‘The establishment of a new resource base’.

Notably, Tainter is sceptical of this in the book, yet includes it because he sees it as an aspect of archaeological research which cannot be discounted. As he outlines, in some instances access to new resources caused existing societies to become unstable and collapse – for example, when societies shift from pastoralism, to hunting large animals, or vice-versa.

Now think of this in terms of our modern society: What is artificial intelligence (AI) and automation? AI takes existing electronic and computational systems and, through large-scale parallel data processing and algorithmic interpretation – put simply, a massive increase in complexity using very large amounts of energy resources compared to previous systems – creates a whole-new basis for industrial design, planning, and operation.

Arguably AI is a ‘new resource’, and one which, in a very short period of time, has the capability to redefine the lives of many people in present-day society. And, from the use of AI in ‘war’ (another driver of collapse), to fake news causing ‘social dysfunction’ (another driver of collapse), AI ticks all the boxes as a ‘new resource’ that has the capacity to collapse the underlying society that created it: Not because AI becomes ‘conscious’ and decides to wipe us out, but simply because the scale of change it enacts is so great that the shock caused severs the complex networks maintaining modern society.

Science and technology do not solve problems under the current pattern – ‘the logos’ – which guides modern society: From novel new pollutants to new social fashions, they create more problems by driving the level of human complexity ever higher. Yes, ‘they could be used’ to do the opposite. The reality is that no major movement in society chooses to promote a less complex/more decentralised alternative.

That is the value of Tainter’s book: It demonstrates how it is the patterns of human thinking which drive our social destruction, not simply the material conditions which define our existence.

In mapping the historic causes of societal collapse, Tainter’s work is a window onto the role complexity plays in the way human society evolves, and ultimately causes its decline. Many dismiss this book because of the word, ‘collapse’, and so fail to understand the implications of the word, ‘complex’. At the same time, the principal argument against our society’s future collapse – our modern, improved faculties of science and technology – does not change the underlying trends driving greater complexity. At any point in time, contemporary science and technology are dependent upon emergent trends within our complex industrial society, and so would be unable to respond coherently once social complexity begins to unravel.

The only rational response is ‘simplification’: De-escalating the human footprint on the planet by shrinking social and economic complexity. There are a few, and growing number of figures advocating this. Yet many within the environment movement or green politics, who have the most to gain from such a strategy, dare not talk of this option because of the backlash they fear from wider society. And as no substantive group will challenge the underlying assumptions driving complexity, so the trend of increasing complexity continues unchallenged. Looking to civilisations of the past from our existence today, clearly history does not precisely repeat itself; but it certainly rhymes.

Photo by Raph Howald on Unsplash